“For what is a man? / What has he got? / If not himself, then he has naught.”

—Frank Sinatra (via Paul Anka), “My Way”

Men are a problem that have yet to be solved. The word “problem” should be taken a variety of ways, as the past few years have proven, beyond the shadow of a doubt, that men are broken creatures; the primary cause of all manner of atrocious, violent acts. Men are also a problem in the sense that they’re ill-defined, especially in an increasingly expansive and progressive social landscape. The old definitions and expectations of men are increasingly out of date, especially as most of them — being pillars of strength, primary providers, effortlessly knowledgable, inherently lawful, never showing weakness publicly — only existed to further a capitalist, patriarchal status quo. Although their privileged position in society doesn’t allow them to be thought of as victims, men are nonetheless trapped by antiquated ideas regarding their gender expression. In many ways, they’re incarcerated within a prison of their own making.

Filmmaker Michael Mann became intimately acquainted with the psychological and emotional realities of being a prisoner, so much so that not only are a number of his films concerned with the subject, but his experiences allowed him insight into that unique prison known as masculinity. Mann’s filmography as a director isn’t extensive — just 11 feature films within 40 years — yet those movies are of a piece in their exploration of the male psyche. Mann predominately features men facing an internal crisis that is soon made external, their neuroses spilling out into the real world with drastic consequences. His movies often pit the notions of good and evil, lawful and unlawful, cops and criminals against each other, showing them to not be polar opposites but points on a spectrum. The protagonists and antagonists in Mann’s films tend to be mirror images of each other, all of them caught within masculinity’s shackles.

Mann reached such nuanced insights thanks in part to his worldly upbringing — born and raised in Chicago, he went to grad school for film in London, later moving into directing commercials as well as shooting a number of documentary shorts (including one on the 1968 student revolt in Paris called Insurrection). Upon return to the United States, Mann was mentored into television, writing for a number of crime-based shows including Starsky and Hutch, Vega$ and Police Woman. His work on the latter show led to him making his non-documentary directing debut on the episode “The Buttercup Killer.” Even there, Mann’s artistic themes and predilections can be seen — the killer is revealed to be a man with split personality disorder who dresses up as a nun to commit murders, his gender expression as well as psyche clearly in crisis. Mann almost jumped to features as a writer, working on an early draft of what became 1978’s Straight Time by doing a lot of research at California’s Folsom Prison. Sadly, his script was rewritten, and the project went in another direction.

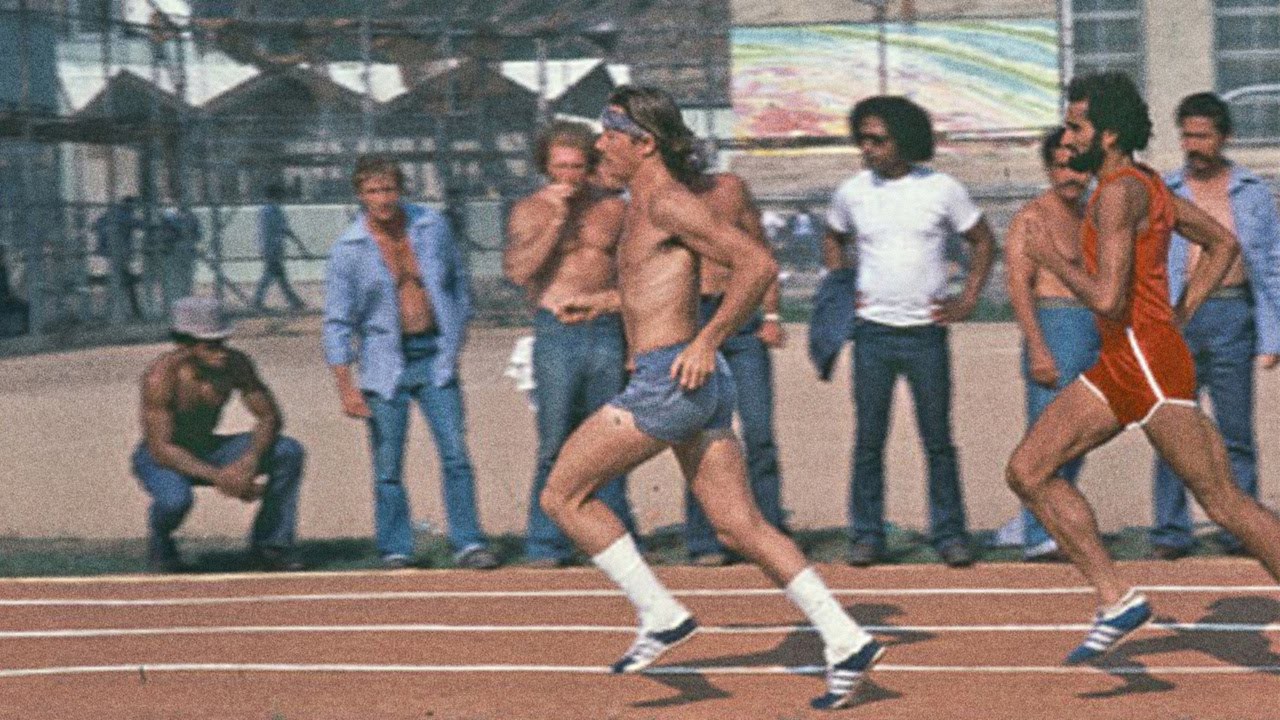

Yet Mann’s time at Folsom was not ill-spent. Thanks to extensive TV work, he was given carte blanche by ABC to pick from a number of scripts to make a TV movie from, and he chose one by Patrick J. Nolan entitled The Jericho Mile. Rewriting it based on his research, Mann decided to not only set the film but shoot it at Folsom, recruiting a number of actual prisoners as supporting characters. Such a choice is the earliest example of Mann’s authenticity, his films exhibiting a high level of verisimilitude and credibility in their performances and dialogue. That authenticism is present right from the first scene of The Jericho Mile, an audaciously cinematic montage (for a TV movie) that portrays a diverse variety of male bodies flexing, gyrating and simply existing on screen. Mann contrasts this parade of maleness with shots of guard towers, fences and concrete walls, the undeniable iconography of the jailhouse. The Jericho Mile’s thesis is laid out sans dialogue right away — this is a story about men in prison, in more ways than one.

More by Bill Bria: The Erosion of Family in the ‘Poltergeist’ Films

The Jericho Mile’s protagonist is Larry “Rain” Murphy (Peter Strauss), a quiet, standoffish convict who finds his own kind of escape through running on a daily basis. His one friend in the joint, R.C. Stiles (Richard Lawson), is the yin to Murphy’s yang — a Black man who is boisterously social, family-oriented and unafraid to make bold moves. The intense friendship between the two not only feeds into the film’s exploration of racial divides, but presages future Mann duos like Crockett and Tubbs from Miami Vice (both the Mann-produced series and 2006 film) and Vincent and Max from Collateral (2004). The Jericho Mile is a hybrid film, a sports movie that’s really a prison movie and vice versa, and as such the usual tropes of both are subverted — prison life doesn’t appear to be that awful at first, but it’s in Murphy and Stiles’ heartfelt conversations that its toll can be seen weighing on the men. “Dreams! Expectations! They never happen, man. They’re the worst.” Stiles laments, vocalizing what the more stoic Murphy later learns firsthand, after the prison warden (Billy Green Bush) invites a professional track coach (Ed Lauter) to train the inmate for potential Olympics consideration. Mann makes The Jericho Mile into an exercise in empathy for the audience, as Murphy pushes himself to become the best athlete he can be, yet is revealed to have committed first-degree murder. It’s especially telling that Murphy’s victim was his own abusive father, leaving him eternally conflicted at his taking the life of a person who he once loved and admired, and in essence was the man who taught him what being a man was all about. Hence the movie’s true victory isn’t Murphy winning a race or qualifying for the Olympics (the latter being understood as impossible by Murphy, since the male Olympic board members he meets clearly view him as a broken and undesirable man) but rather freeing himself from his own prison of isolation and guilt, the proverbial walls of Jericho in his soul falling down, if not the actual Folsom walls.

Mann’s next film and first theatrical feature, Thief (1981), also concerns a man freeing himself from a prison of his own making, albeit at large cost. Where most of Mann’s other films tend to be ensembles, Thief is tightly focused on its protagonist, Frank (James Caan), emulating that character’s own intense drive. The film’s opening sequence is as masculine and eroticized as The Jericho Mile’s, with Frank expertly breaking into a safe filled with uncut diamonds, using a heavy, phallic drill to plunge into the safe’s door, the image complementing Frank’s sweaty visage and the rain-slicked streets of Chicago, so much so that sparks literally fly. In addition to being coded as masculine, Thief’s heist sequences act as an extension of Frank’s professionalism and pragmatism. He doesn’t just have a plan for the jobs he pulls, he has a plan for his entire life — spending his formative years incarcerated caused Frank to literally construct a collage representing his personal goals. Those goals read like a heterosexual male checklist: stable finances, nice suburban house, a wife and a couple of kids. Being so long removed from society makes Frank feel like he has to “catch up,” as he so rationally explains to Jessie (Tuesday Weld) during the first of several iconic diner scenes in Mann’s film. Unlike other crime film protagonists, Frank isn’t a live wire or greedy capitalist or sadistic manipulator — he’s the epitome of the patriarchal Alpha Male, the “Father Knows Best” type who has all the answers, the determination and the skill to make things happen.

More by Bill Bria: The Disaster Area: From ‘Airport’ to ‘Airplane!’ – Part Two

Mann isn’t about to let the self-assured masculinity of Frank to thrive without consequence, however. As ruthlessly pointed out by the mob boss Frank gets tied into, Leo (Robert Prosky), Frank’s construction of the ideal life has left him vulnerable to being owned and manipulated, his world now filled with value that can be lost. In essence, Frank has built a new prison for himself, the goals in his collage as constraining as concrete walls and iron bars. Frank’s solution, then, is as pragmatic and calculated as any of his heists or his marriage or his adoption of a child had been, deciding to literally and figuratively tear it all down. The climax of Thief is so thrillingly subversive because, in a more typical crime film, Frank’s downfall would be due to an enemy he didn’t see coming, his hubris blinding him to the threat. There’s still an element of that in Thief, represented by Leo, but the actual apocalyptic destruction of everything Frank holds dear is wholly perpetrated by himself. In addition to this being yet another example of Frank’s coldly rational character, there’s a sense of male petulance in it, too, a “take my ball and go home” attitude to Frank’s dismantling of his life. To Mann, true freedom comes at a heavy price, and doesn’t look anything like one expects.

With Mann’s next film, The Keep (1983), he furthers his concept of prison and his portrayal of the duality of men, moving from characters on the wrong side of the law to full-on Good and Evil. Based on a horror fantasy novel by F. Paul Wilson, The Keep is an anomaly in Mann’s filmography for several reasons, not the least of which is its studio, Paramount Pictures, cutting Mann’s original 210-minute cut down to 96 minutes, rendering the film somewhat incomprehensible. As such, Mann’s ultimate message with The Keep is made vague, but his intentions can still be seen. Set in Romania in 1941, the film sees an ensemble of characters converge on the titular Keep, a massive and imposing structure in the middle of a small village that the Nazi Wehrmacht have seized control of. Despite ominous warnings from the villagers who have kept watch over the Keep for centuries, some Nazis attempt to steal a silver cross within one of the walls, thereby unleashing an ancient demonic figure known as Molasar (Michael Carter). As the villain begins to murder the occupying all-male force, a conflicted and reluctant Nazi Captain, Klaus (Jürgen Prochnow) clashes with a sadistic SS officer named Erich (Gabriel Byrne) over the morality of their actions, while a dying Jewish professor, Cuza (Ian McKellen), is spared from transport to a concentration camp and assigned to figure out what’s killing the soldiers. Cuza, who naturally despises the Nazis, is approached by Molasar, and the demon offers to wipe the fascist force from the face of the Earth if Cuza will set it free.

More by Bill Bria: The Disaster Area: From ‘Airport’ to ‘Airplane!’ – Part Three

The Keep is, at its core, a parable of ethics and morality viewed through a male lens. As is typical in morally ambiguous horror tales, the side of Evil is more seductive, with Cuza attempting to do the righteous (if not right) thing, realizing almost too late how he’s compromised his own morals in the process. Klaus similarly undergoes an awakening at the wrong time, not realizing the lengths to which the sociopathic Erich will go. The film is a critique of men having misplaced faith in themselves — “you believe in gods, I believe in men,” Cuza arrogantly tells a local priest, an attitude that actual supernatural being Molasar easily slips his selfish, evil goals into. Molasar’s opposite number in The Keep is the immortal warrior Glaeken (Scott Glenn), and Mann has fun emphasizing their duality in several ways. Both Molasar and Glaeken are noticeably muscular, their bodies distorted into pseudo-idealized shapes, a continuation of the director’s observation of the male body. Molasar has no exact form, being composed of smoke and fog, while Glaeken has no reflection — both states of being comment on the distortion of the male image just as the characters distort morality. Molasar is passionate where Glaeken is eerily cold, the latter’s relationship with Cuza’s daughter, Eva (Alberta Watson), his attempt to gain humanity. Like Jessie in Thief, Eva is an outlier in the male world of the film, a third perspective trying to break through the rigidness of the men surrounding her. In Mann’s original cut of The Keep, she succeeds, redeeming Glaeken after the cold, inhuman warrior defeats his enemy and is rewarded with humanity. In the released version of the movie, however, Glaeken is lost, trapped eternally within the Keep along with Molasar. Despite these divergences, The Keep is about man facing his own morality, an endless struggle within and without, a prison that there may never be an escape from. While The Keep flailed at the box office, it was not to be the end of Mann’s career, and the filmmaker would soon reach new heights not just commercially but artistically, continuing to explore masculinity and morality while transforming the crime film and other genres along the way.

To be continued…

Bill Bria (@billbria) is a writer, actor, songwriter and comedian. ‘Sam & Bill Are Huge,’ his 2017 comedy music album with partner Sam Haft, reached #1 on an Amazon Best Sellers list, and the duo maintains an active YouTube channel and plays regularly all across the country. Bill‘s acting credits include an episode of HBO’s ‘Boardwalk Empire’ and a featured parts in Netflix’s ‘Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’ and CBS’ ‘Instinct.’ His film writing can also be seen at Crooked Marquee as well as his own website. Bill lives in New York City.

Categories: 1970s, 1980s, 2021 Film Essays, Action, Active Film Series, Crime, Drama, Fantasy, Featured, Film Essays, Horror, Mannhunting by Bill Bria, Sports

4 replies »