In a familiar film noir scenario, the jaded male protagonist finds his foil in the form of a duplicitous female lead, the infamous femme fatale. They often meet by chance and their relationship is frequently based on ruinously opposing aims. Different noirs will invariably approach their inevitable downfall and place the blame on either or both of these characters, but what can get lost in this ultimate inditement is the impetus for the connection in the first place. Surely, this sometimes includes disreputable motives like greed or self-seeking advancement. Other times, even if rarely, there is a genuine, deeply felt emotional bond that unites these wayward romantics. In the end, though, in both cases and however the relationship concludes, the man and woman have willingly played a part. They are guilty in their own way because, after all, it takes two to tango.

Enter director Masahiro Shinoda and his 1964 Japanese noir Pale Flower, where the man here is Muraki (Ryô Ikebe), a hired gun just released from prison after three years. He meets his match, Saeko (Mariko Kaga), at a clandestine gambling hideaway. But before that, he arrives in the film’s opening minutes at Tokyo’s Ueno Station, where he is overwhelmed by the bustle and the crammed bodies and lifeless faces; perpetually disconnected and cynical, he wonders in voiceover what they’re all living for. Despite this social detachment, Muraki is nevertheless struck by Saeko, as he should be, and as others certainly are. Shinoda has commented on Ikebe’s “erotic and graceful presence,” particularly in the way he walked, while, by contrast and complement, Kaga maintains what Shinoda terms an “uncanny” presence. Saeko indeed possesses a palpable air of mystery, which surrounds her and follows her in any setting but is especially notable on the gambling floor. There is an incongruity to her attendance, not only as the lone female representative, but in her very nature — she is out of place every place she goes. Though she is hardly the black-clad temptress, nobody knows where Saeko comes from, and her confidence and ostensible indifference rests uneasily for those, like Muraki, who are beguiled by her enigmatic, aloof and indefinite cool.

Read More at VV — The Beautiful Brutality of Sergio Corbucci’s ‘The Great Silence’

The hanafuda or “flower card” game tehonbiki, played by Saeko and generally observed by Muraki, will be returned to throughout Pale Flower, where the consequence of its risks and rewards are underscored by the enclosed entrapment of the rectangular row of players positioned around the centerpiece mat and by the aural intensity of the shuffling cards (composer Toru Takemitsu, who worked closely with Shinoda from the film’s script stage to the inspired implementation of his dissonant score, included the sound of tap dancers to heighten the acoustic prominence of the participants making their moves). Emphasis is also placed on the procedure and ritual of the game, the tantalizing convergence of variability with systematic order; and, of course, there is the anxious draw of money to be quickly won or lost in a matter or mere moments. Saeko, for one, continually seeks higher and higher stakes, a parallel pursuit to Muraki’s insatiable quest for violent assignment back within the ranks of his criminal crew. But neither enterprise comes easily. While he was away, it seems, rival gangs began shifting alliances in the name of territorial dominance, and Muraki, now something of an uninformed outsider, is told to lie low. His accustomed gangster domain has moved on without him, so while Saeko has no apparent past, Muraki’s own history has suddenly become irrelevant. Together, then, they forge an unsteady path in a new, transitory and perilous present.

Distributed by Shochiku studios and written by Masaru Baba and Shinoda, based on a story by Shintaro Ishihara, Pale Flower (Kawaita hana, or “dry” or “withered” flower) is a magnificently emblematic example of the stylization, self-consciousness and independent spirit that defined the Japanese New Wave. And the visual trappings of noir, to which these films were indebted to varying degrees, are compellingly evident, from the darkened narrow alleyways to the glistening city streets illuminated by reflections of neon light on delicately saturated surfaces. Though shot in Yokohama, the scenic elements are such that Pale Flower assumes universal familiarity in terms of its conspicuous aesthetic as well as its potent rendering of existential dread. Danger lurks in nearly every corner of the picture’s shadowy Grandscope frame, like the silently skulking Yoh, a new man on the gangster scene played with stoic peril by Takashi Fujiki. Yet even in public areas of apparent safety, like a bowling alley, there exists the persistent potential for random and sudden ferocity.

Read More at VV — Know the Cast: ‘Black Bird’

Implementing dramatically expressive angles and subtle camera movements, Shinoda aimed to establish what he called the “psychedelic aesthetics” of Pale Flower, reflecting the anxiety and malaise of not only the insecure underworld but the Cold War tension in Japan at the time, as a nation wedged between the dual manipulations and uncertainties of the Soviet Union and the United States. In the political sphere, like in Muraki’s province of hesitant operation, there was, for Shinoda, a “postponed maturity.” This also may explain Pale Flower’s jarring shifts in tone. For example, Muraki seeks initial solace in his unfaltering lover Shinko (Chisako Hara), but he can also be effortlessly cruel to the easily discarded young woman (“Is your stomach upset?… your breath smells bad.”) and indifferent to her concerns. There is also Muraki’s boss, who pragmatically urges him to kill a mark with a knife rather than a gun, but in a flash proceeds to chide the way a passing nurse carries a newborn baby. And when Muraki is appalled after Saeko tells him she “shot up the other day,” scolding her only to be reassured as nonchalantly as ever, “it was no big deal,” he decides to take her along with him on this deadly duty, a prospect, he suggests, even better than drugs, as if it were a casual date.

Read More at VV — Soundtracks of Television: ‘Black Bird’

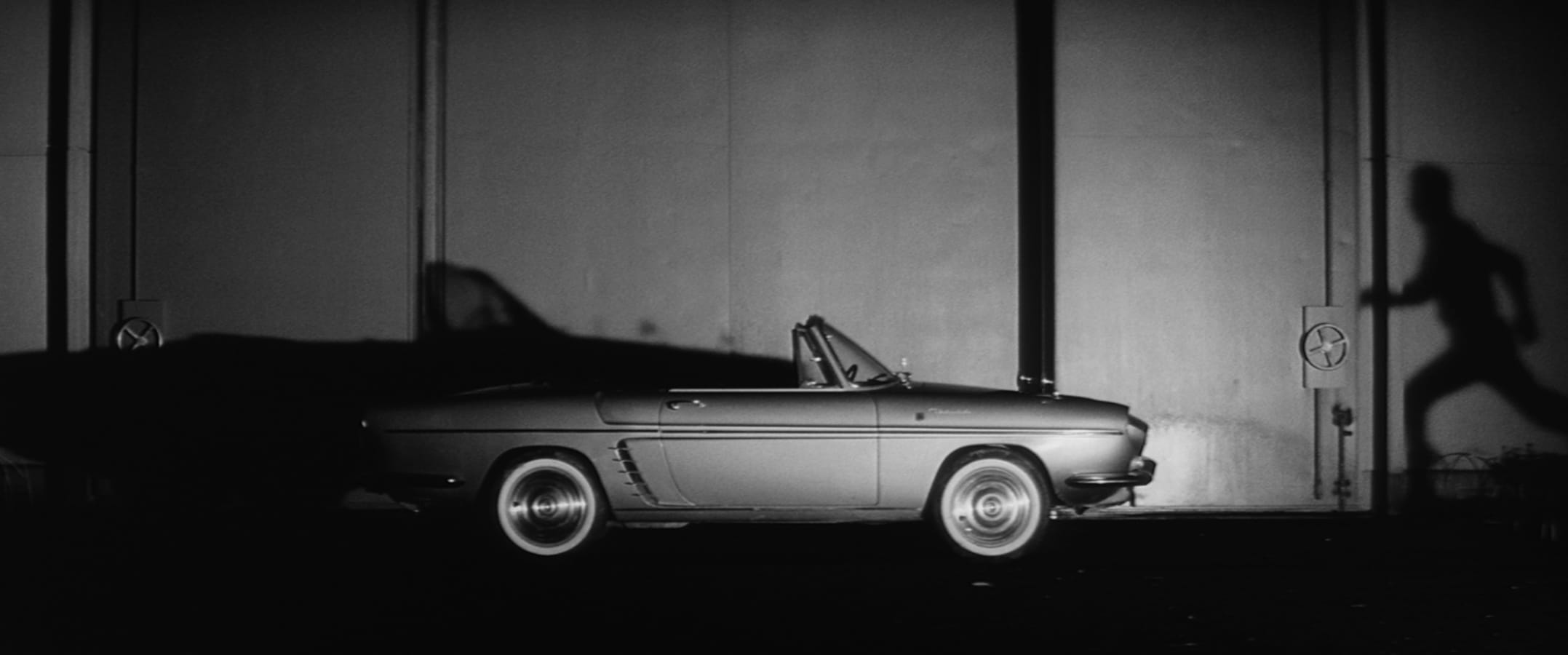

So how, in this world of impropriety, death and depravity can lovers, even ill-fated lovers, exist? Maybe they can’t, but Ikebe, who was 45 at the time and had been acting for more than two decades, and Kaga, who was just 19 in 1964 and had only been acting for around two years, make a compelling case all the same (Shinoda called Pale Flower a “romantic and utterly irrational love story” while critic Chuck Stephens dubbed it a “sumptuous sonnet to unrequited amour fou”). Caught between the trifold forces of self-destruction, mortality and world-weary desolation, Muraki and Saeko talk about their life in reflective bouts of mindfulness, but they do so without passion or commitment. A surreal dream sequence illustrates the depths of Muraki’s torment — namely his latent, unstated feelings for Saeko — yet even that only serves to underscore his impassivity. In any event, and although the influence of their association remains fleeting and precarious, Muraki and Saeko truly come alive when together, when they connect, respond and jointly lash out against the nihilism and ambiguity of their daily lives. And per noir tradition, this alliance is forged in the dark, when the city fades into obscurity and an insular world comes into focus, and when intrigue leads to tortuous, if not fatal, obsession. But that’s where these lost souls belong. It’s where they thrive. It’s where they live and it’s where they can die. “I wish the sun would never rise,” Saeko says during an early morning joyride that concludes in an impromptu street race simply for the thrill of it all. “I love these wicked nights.”

Jeremy Carr (@jeremyrcarr) teaches film studies at Arizona State University and writes for the publications Film International, Cineaste, Senses of Cinema, MUBI’s Notebook, Cinema Retro, Movie Mezzanine, Cut Print Film and Fandor’s Keyframe.

Categories: 1960s, 2021 Film Essays, Action, Crime, Film Essays

You must be logged in to post a comment.