No other film has dissected narcissistic masculinity with the same gashing incisiveness as Naked, Mike Leigh’s stygian vision of injured ego spiralling into self-annihilation. Released in the post-Margaret Thatcher gloom of 1993, the film stands to this day as one of the greatest character studies ever committed to the screen, examining one of the most profoundly, desperately lonely men ever conceived on the page. That man is Johnny Fletcher (David Thewlis), a vagabond as vicious as he is charismatic, who steals a car and drives from his hometown in Manchester down to London, after a rough sexual encounter in a back alley goes dangerously wrong.

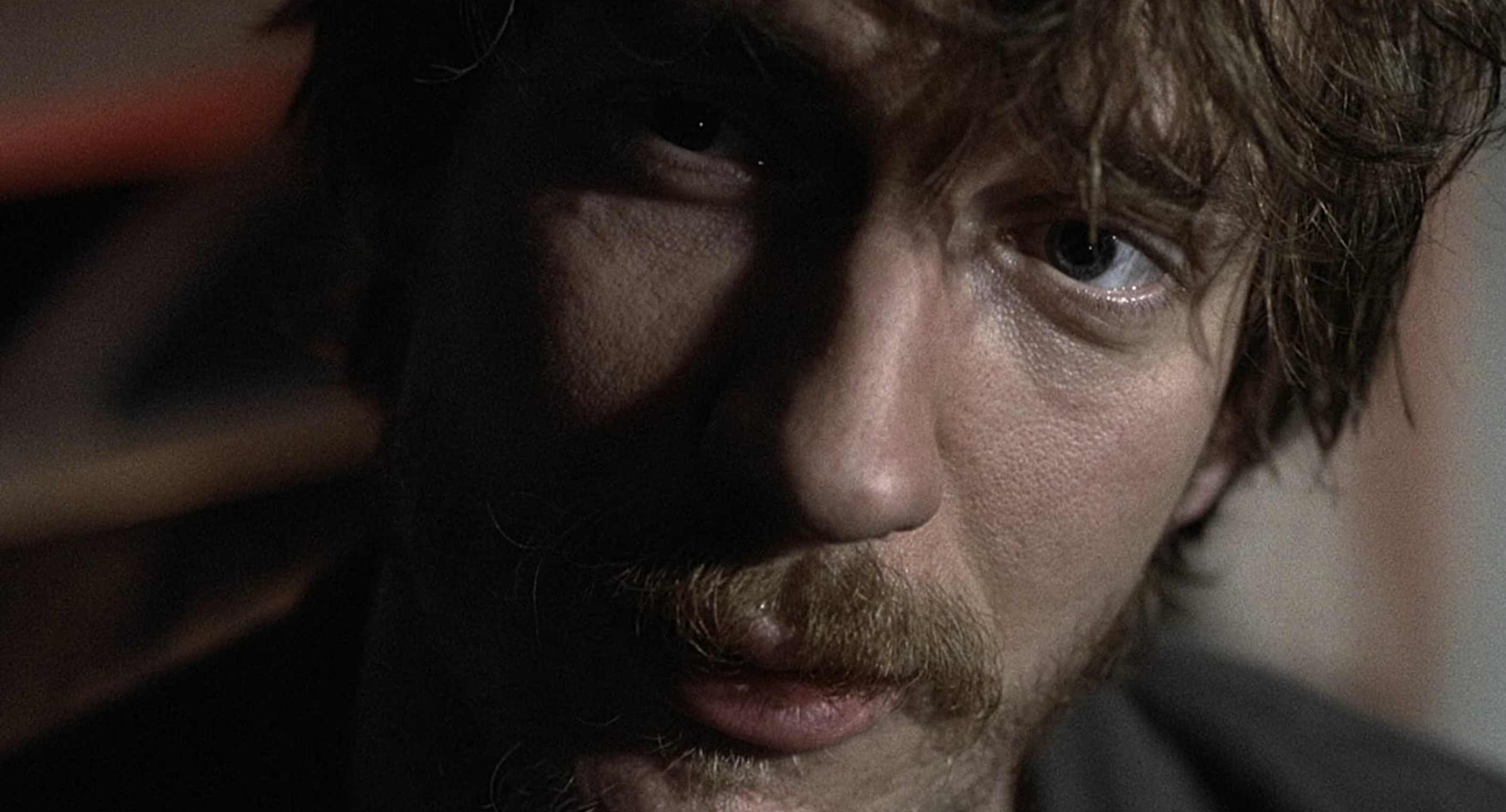

Johnny isn’t just any old wretch — behind the beard and the pallid complexion, he’s some sort of virtuosic modern wordsmith and orator, or so he’d like to imagine. There are few moments in Naked that aren’t filled with the sound of his voice, as he rattles off blistering diatribe after blistering diatribe about anything and everything to whatever living organism with eardrums is nearby. He’s educated and articulate, well-versed in subjects ranging from philosophy to astronomy — and if his brain was wired differently, he might be somewhat interesting to talk to. But it’s clear that healthy or productive conversation with Johnny is pretty much impossible — in his eyes, people should be bulldozed and humiliated, not engaged with. He’s a raging misanthrope, filled with rancour and cruelty, who relishes in particular the opportunity to bully and degrade women. As he lurches across the dour capital city in Naked, armed with a mouth like a machine gun, Johnny rips through every unfortunate soul that he meets with indiscriminate, devastating verbal firepower. By the time his rampage sputters to a halt, the destitute streets are strewn with the broken minds of his victims, including his own.

What makes Johnny so lethal is the precision of his onslaughts — he’s quick to identify points of emotional vulnerability, and even quicker to stick the knife in. That much is made immediately obvious as he wastes no time in picking apart the life of his Mancunian ex-girlfriend Louise (Lesley Sharp), whose London residence is his first destination after fleeing the North. They’ve barely finished greeting each other in Naked before Johnny goes straight for the jugular, taking full advantage of their intimate history in order to make his method of destruction that much more efficient. He can tell instantly that she’s dissatisfied with her job in London, so his first move is to scornfully dismantle her professional aspirations, asking her: “Is it everything you hoped it would be?” He can tell that she still has lingering feelings for him, so he callously ridicules the affectionate postcard that she sent him. And he can tell that she has no love life, so he mocks her for sleeping in a single bed, and then tries to wound her further by exchanging salacious words with her drugged up housemate Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge), as a prelude to meaningless sex. Every sentence, every word, every syllable, is measured for maximum damage in Naked — to tear his victims down, to make them realise their own folly and hate themselves for it.

Why does he attack in this way? Why is he so compulsively barbaric with his speech, so keen to inflict pain and trample upon optimism? Well, because otherwise he couldn’t possibly survive. Because whatever hatred Johnny feels for the world around him in Naked is eclipsed by the hatred that he feels for himself. In isolation, his tirades don’t necessarily betray that self- hatred, because the image that they consciously and interminably project is of a man who’s perfectly content in the knowledge that all human life amounts to emptiness. In Naked, His strategy is to launch his offensives from a tower of nihilism, positioning himself in the role of an enlightened messiah, whose words of cold truth will emancipate the people of Britain from the stagnant cesspools of their delusional hopes and dreams. He, unlike the rest of the world, has come to terms with and embraced his own insignificance within the cosmos — only fools deserving of contempt still cling to the illusion that their lives have meaning or purpose. “We’re not fucking important,” he says of mankind, “we’re just a crap idea.”

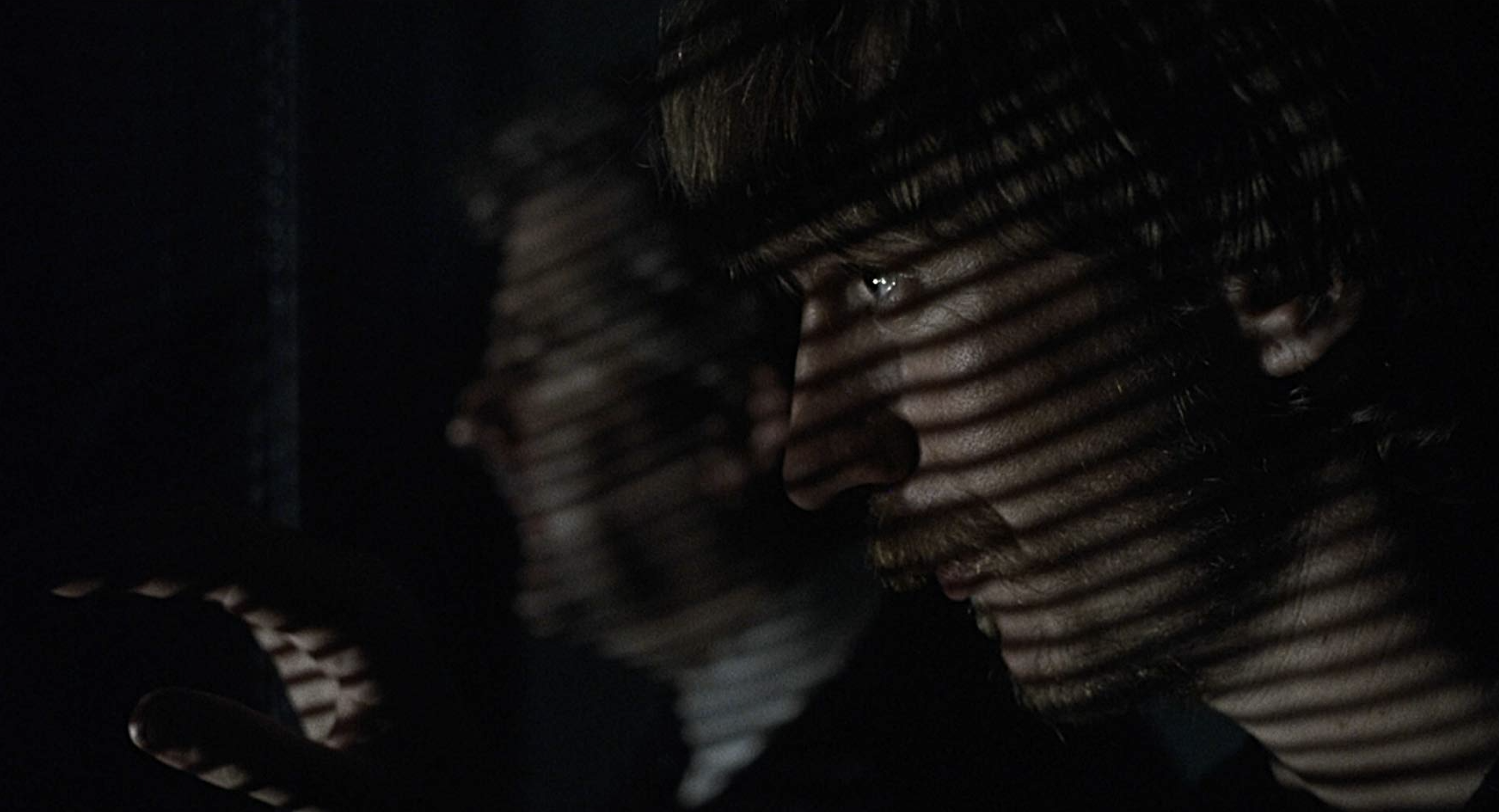

But those streams of aggression are nowhere near as significant as those moments of solitude in which Johnny is left with nobody to talk to, nobody to disparage and denigrate. In Naked, Leigh tethers viewers to Johnny’s headspace, forcing viewers to regard him at his highest and lowest. When he’s deprived of prey, Johnny’s demeanour is almost unrecognisable from when he’s on the hunt — slouching, twitching, grimacing. To witness Thewlis in action here is to witness a performance that extracts staggering emotional nuance from the extremities of human behaviour. Watch how the animated exhilaration of ranting ebbs away, supplanted by hushed irritation; how the thrill of sating his bloodlust gives way to depressed starvation; how the arrogance evaporates, leaving behind only a residue of uncertainty. The shoulders slump, the head drops, the eyes flicker with bemusement, the mouth contorts with impatience. It’s as if all of the caustic anger that usually erupts from him is turned inwards, corroding his insides. The harsh reality is that when Johnny is alone in Naked, with only his own private thoughts to keep him company, he becomes torturously aware that he embodies the very thing that he detests — a person racked with the fear of unimportance to which he claims to be immune, trembling at the idea of his own nothingness.

In this light, Johnny is rendered no less appalling or repulsive, but perhaps more pitiable. More than anything, he’s pathetic. The role of logorrheic tormentor that he’s fashioned for himself is revealed to be little more than a coping mechanism in Naked, an ineffectual way of escaping from the claustrophobic confines of his own mind by verbally assaulting everybody, anybody else, with all guns blazing. So intensely does he loathe what he’s become that his only respite comes when he’s scourging others, in the vain hope that their suffering might somehow attenuate his own feelings of self-disgust, and justify his woeful existence. Lashing out is an excuse for him never to admit that he’s hurting, never to address his own malignant insecurities.

Of course, there’s no way to sustain such a twisted dependence on brutalisation and sadism for very long in Naked, and Johnny’s plight is made all the more complicated by the inconvenient fact that sometimes, his victims bite back. One such victim is Brian (Peter Wight), a night watchman patrolling an eerily empty office building, who engages with Johnny in a sprawling nocturnal debate about time, religion and the end of the world. At first, Brian seems to be low-hanging fruit for Johnny to pluck and squeeze. He’s painfully lonely, dreadfully boring, sexually frustrated and plagued by self-loathing. He’s everything that Johnny finds abhorrent — a man unwilling to let go of the potential for greater meaning in his existence, insisting that the end of all human life is impossible. “I know I was here in the past, before I was born,” says Brian, “so I know I’m going to be here in the future, after I’ve died.” It’s all so vague, so fanciful, and Johnny does indeed tear him apart — lambasting him for his naivety, punching holes in his beliefs, trying to snap whatever it is that keeps him holding on. “It doesn’t matter how many past or future existences you have,” Johnny retorts, “because they’re all going to be riddled with grief, and anguish, and sadness, and death. You see, Brian, God doesn’t love you. God despises you. So, there’s no hope.”

And yet, strangely, it’s Johnny that emerges from their encounter as the one who’s closer to falling apart. For all of his loud, meandering pontifications about the futility of goodness, Biblical prophecies of extinction and the cruelty of God, intended to make Brian despair, Johnny is undone by Brian’s small, muttered exhortation: “Don’t waste your life.” It’s the one piece of advice that Johnny receives, and it hits him like a sledgehammer. He has no response, no clever remark, no viciously concocted abuse. He just sits there, his eyes darting downwards in anxiety and panic. Brian cuts straight through the bravado, straight through the bullshit, and in just a few admonishing words expresses something more concrete and cogent than Johnny could possibly express in a thousand of his rants — a call to find fulfilment before it’s too late. As easy as he might be to deride, even Brian can recognise that Johnny is a kindred spirit to the people that he abuses — that Johnny lives with the very same constant, paralysing fear of never knowing what the hell he’s doing or where the hell he’s going.

But the person that’s most acutely cognisant of Johnny’s fear, more so than maybe even Johnny himself, is Louise. Thewlis has earned innumerable plaudits over the years for his performance, and rightly so, but Sharp as Louise is his understated equal, a counterpoint of exhausted sadness to Johnny’s vehemence. “You look like shit,” observes Louise, after coming home to find him lying on her sofa. “Just trying to blend in with the surroundings,” Johnny replies, in a rare bout of repartee that departs from his usual unilateral conversational style. Their chemistry in Naked is immediately endearing, in spite of, or maybe because of, their mutual weariness. Their knowledge of each other might streamline Johnny’s formulation of insults, but it simultaneously makes Louise’s defences tougher to breach. Other women are magnetically drawn to Johnny, beguiled by a vulnerability to which they hope to connect, allowing him to get dangerously close to them — but not Louise, not anymore. She’s not like the older woman that Johnny meets on his midnight excursion, who he seduces and then scorns for asking to be physically abused during sex: “You think you can recapture your youth by fucking it?” Nor is she like the already miserable Sophie, who’s made to feel even more peripheral and abandoned than she already does, after Johnny becomes violently intolerant to her yearning for romantic love.

No, Louise knows better than to allow herself to be hypnotised by Johnny’s maniacal charm, or to try to match him blow for blow, word for word. She knows that he attacks in order to compensate for his emasculating feelings of powerlessness, so she makes sure not to concede any ground, not to let him feel as if he’s in control. It’s better to keep him at arm’s length — get comfortable, enjoy the spectacle, have a cigarette. She bides her time, absorbing his strikes, waiting for him to punch himself out. And whenever he does succeed in hurting her, she’s shrewd and sturdy enough not to let it show, so as not to give him the satisfaction that he so desperately craves.

Louise stands out in Naked because the way in which she deals with Johnny is so distinct from everybody else, so divorced from their revulsion, their outrage, their clinginess. When she looks at him, her eyes are infused not so much with anger, annoyance or passion, but with the sort of deflated disappointment of somebody reflecting upon and mourning missed opportunities — grieving for what Johnny could have made of his life, and what their relationship could have become. Not that she feels as if it’s her responsibility to save or redeem this reprehensible individual, to somehow drag him out of this mire of his own making — besides, a man like Johnny would probably react badly to the suggestion that he needs help. When she speaks to him, her words are deliberately designed to probe him where she knows he’s sensitive, in order to get a good sense of where they stand.

“Were you bored in Manchester?” she asks, as a sort of litmus test for his mental state. Johnny’s answer is resounding: “Was I bored? No I wasn’t fucking bored. I’m never bored. That’s the trouble with everybody — you’re all so bored. You’ve had nature explained to you, and you’re bored with it. You’ve had the living body explained to you, and you’re bored with it. You’ve had the universe explained to you, and you’re bored with it. So now you just want cheap thrills and, like, plenty of them, and it doesn’t matter how tawdry or vacuous they are, as long as it’s new, as long as it’s new, as long as it flashes and fucking bleeps in forty fucking different colours. Well whatever else you can say about me, I’m not fucking bored.”

An impressive lecture, no doubt, but again the world around him isn’t really who it’s aimed at. This is Johnny expounding upon his own condition — the anguish of trying to understand everything, and ultimately understanding very little. He’s read Homer, and he’s bored with it. He’s read about the butterfly effect, and he’s bored with it. He’s read the Bible, and he’s bored with it. He’s read just about everything that there is to read, and he’s bored with it, because none of it has even in the slightest way helped him to understand his place in the bigger picture. His rant merely confirms what Louise already suspected — that he’s still just as clueless and despondent as everybody else, and still obstinately, tragically in denial of his own crisis.

Naked is just as emotionally raw now as it was when it was made, just as acrid and acerbic, and only seems to gain pertinence with age, as the toxic traits of masculinity into which it offers insight become more and more clearly identifiable in society. It has even more to say now about the destructiveness of men who fail to resolve their feelings of disappointment at their lack of purpose, and who then hazardously misplace their rage, too consumed by ego to meaningfully reach out. In Johnny, we see what becomes of such a man, teetering on the precipice of total catastrophe — a man without friends or foundations, whose spirit has been irreparably crippled by anger, who can never retake his place amongst any form of family or community. And yet, Leigh and Thewlis leave viewers with a hint that some part of that man could still be salvaged. There’s a fleeting, aching moment of reconciliation with Louise, in which the prospect of tenderness presents itself to Johnny — and he walks away from it, knowing that he’s still too destructive, too despicable to be near somebody who might care for him, and that he still has a lot of searching left to do. As he hobbles with grim persistence into tomorrow, any condemnation of him might yet be tempered by compassion.

Cian Tsang (@CianHHTsang) studied English Literature at UCL, and is now a writer based in London. He spends most of his time listening to the Twin Peaks soundtrack.

Categories: 1990s, 2020 Film Essays, Comedy, Drama, Featured, Film Essays

You must be logged in to post a comment.