Crime Scene is a monthly Vague Visages column about the relationship between crime cinema and movie locations. VV’s Salvatore Giuliano essay contains spoilers. Francesco Rosi’s 1962 film on The Criterion Channel features Salvo Randone, Frank Wolff and Pietro Cammarata. Check out film essays, along with cast/character summaries, streaming guides and complete soundtrack song listings, at the home page.

*

An early cut in Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano highlights one of the central, motivating ideas behind the film: the links between power and geography, and the individuals that occupy the landscape. In 1945, Sicilian nationalists debate the next steps to take on their quest for independence. They are in an office in Palermo, the capital of Sicily, remonstrating with each other, and the leader waves his hands around furiously. The next shot cuts to a figure, far off into the mountainside, waving his hands frantically, messaging someone on the other side of the valley. Rosi transitions from the city (the seat of local politics) to the raw, ragged countryside, where politics are born, moulded and shaped.

Salvatore Giuliano remains a benchmark in biographic films, though it is not a biopic. The film’s titular figure is only ever seen as a corpse, or maybe in the far distance. Rosi, one of a cache of staunchly left-wing Italian directors of the era, understood Salvatore Giuliano not as a way of retelling the subject’s story but of digging under the social and political context from which he emerged. For some, the real-life Giuliano was a Robin Hood figure, upending the legal order in favor of the poor and downtrodden. For others, he was a mafia-connected bandit who stole and terrorized the countryside. For others still, Giuliano was a patsy and a pawn who, by sheer dint of his confidence and audacity, lucked into more infamy than his handlers wanted.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Bandidos’

Rosi cuts between Giuliano’s death in the streets of Castelvetrano, his activities as a bandit (including the massacre of working-class peasantry at Portella della Ginestra) and the high-profile trial of some of his associates after his death, including Gaspare Pisciotta (Frank Wolff). The removal of Giuliano from his own story ensures a different effect — that these events are told in terms of the impact they have on the society around them, rather than on the protagonist himself. In this way, Rosi produces an artwork that prioritizes a collective view of events rather than an individualized view — a genuinely socialistic portrayal, even if the subject is anything but socialist.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Television: ‘The Sympathizer’

Key to Rosi’s collective approach is landscape. For one thing, the filmmaker always establishes the settings. Many of Salvatore Giuliano’s events take place in the vicinity of Montelepre, the subject’s birthplace, a small town about 30 kilometers away from Palermo. A panning shot atop the hills showcases the landscape and describes the neighboring towns (Giardinello, Torretta, Carini, Partinico, Alcamo — a loop which would take about an hour and a half today on small roads), as well as the nearby peaks. Rosi ensures that that viewers nearly always know the setting; a remarkable feat given that Salvatore Giuliano’s scattered chronology means it is often quite deliberately challenging to fully understand the story’s timeline. There are rarely any obvious clues when a scene starts. Instead, Rosi leaves audiences to figure it out based on contextual clues, such as whether Giuliano is being referred to in the past tense or not.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Ripley’

Rosi communicates the settings in Salvatore Giuliano but not the specific timeframes. The titular figure emerges from the landscape of Sicily and its history as a distinct region, separate culturally and politically from the Italian mainland. As a Neapolitan, Rosi understood all too well the vast gulf in Italy’s north-south divide. Since the country’s unification in 1861, the North has hoovered up most of the infrastructure, investment and high-powered jobs, while the South is left to depopulate in poverty, at the mercy of mafiosos and sneered at by northerners. Even today that inequality persists: Lombardy in the north has a GDP-per-capita of 127% of the EU average, while Calabria in the south has a GDP-per-capita of just 57% of the EU average. Italy remains the most geographically unequal country in the EU.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘A Haunting in Venice’

Salvatore Giuliano’s subject becomes a ghost in the film’s landscape. His contradictions — being perceived as a Robin Hood-type popular with the local peasantry as well as a vicious anti-communist who massacres innocents — are part of the same tapestry, part of the same continuous logic. Rosi, for his part, avoids any judgemental attitude, presenting these conundrums in an objective, realist manner. The characters around the story are concerned with their immediate aims: journalists want to cover the truth of Giuliano’s death; Pisciotta and company wish to avoid prison time and retain their loyalty to their leader; the carabinieri are tasked with bringing the bandit to justice, dead or alive (much like a Western).

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘No One Gets Out Alive’

But Rosi complicates this seemingly “objective” viewpoint at multiple points throughout Salvatore Giuliano. A common perspective sees the camera position in a nearby vantage point, like the second floor of a building overlooking a scene. At first, this seems to be something like a “God’s Eye” view of events from a distance. Yet more than once, these vantage points are interrupted by sounds of gunfire, an ambush, usually from above. Suddenly, Rosi communicates the viewpoint of the attackers, a subjective perspective in which he implicates audiences in the violence.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Hand of God’

Many of the gunfights in Salvatore Giuliano are startingly brutal for their time. Rosi’s depiction of guerrilla tactics harks forward to Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), another film by a left-wing director which analyzes the social-political causes of a conflict rather than focusing on any specific protagonists. Their occurrences — brutal yet almost matter-of-fact –are motivated by the construction of political power, whether that is the carabinieri and the military sent to quell Giuliano’s uprising, the presence of Sicilian nationalist rebels or the peasants gathering at Portella della Ginestra.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Fury’

These gatherings in Salvatore Giuliano take place in rural landscapes, with figures set against the rugged Sicilian valleys or its storied towns. They are messy scenes, with characters running everywhere and easy individual identification hard to find. History, and the crimes of Giuliano and his men, are hard to parse in the moment. Who did what and why is rarely obvious, and Rosi’s filmmaking reflects this. Despite Salvatore Giuliano’s realist manner, many scenes utilize hard shadows and mannered group compositions to heighten the sense of style. It’s like a myth being crafted in real-time from seemingly mundane objects and stories; a Robin Hood set in the landscape undercut by the very real and very bloody trail Giuliano left behind.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Blood & Gold’

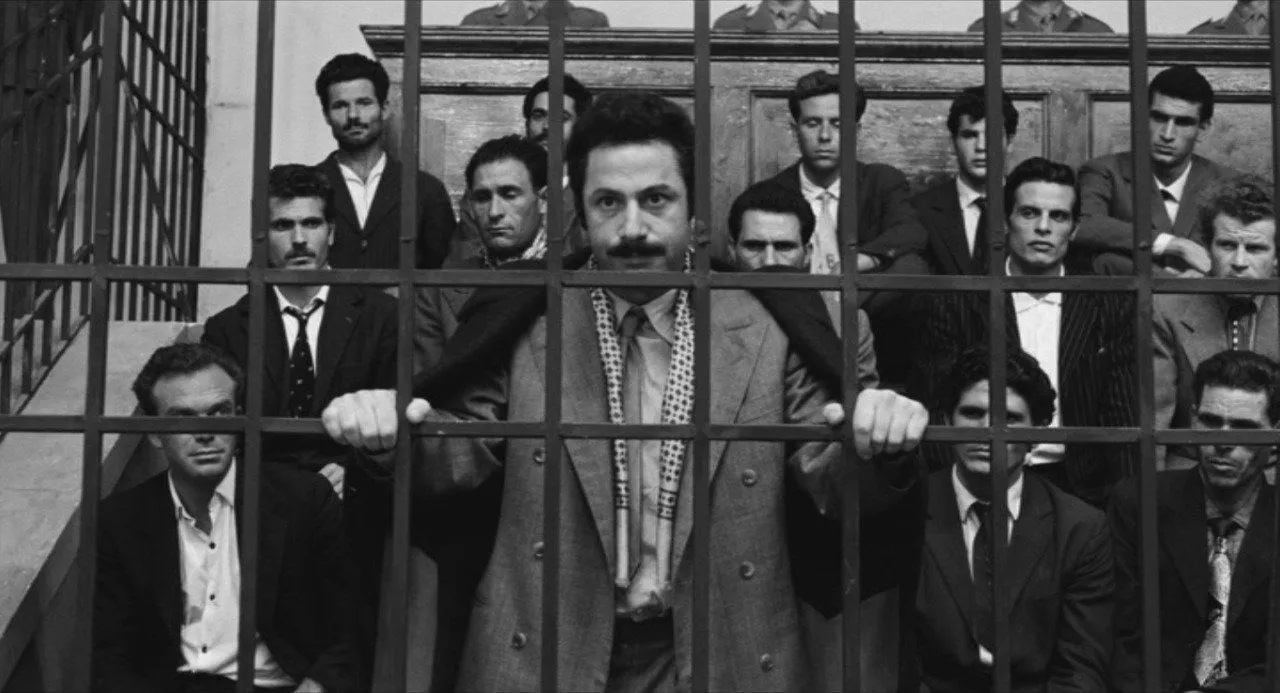

That all changes in Salvatore Giuliano’s second half, which largely takes place in the courtroom as the subject’s band is arrested and put on trial. Partly, this shift to the courtroom mirrors the effect of post-war Italian policy to Sicily. Traditional, semi-feudal organizations such as the mafia become superseded by the demands of the centralized state as Sicily “modernized,” albeit in a semi-colonial, extractive manner which saw many of its people emigrate either within Italy or further afield. In this section, there’s a judge and court admin sitting centrally, overseeing lawyers, press, onlookers and the accused either side of them. Their power in this sphere is absolute, though frequently challenged by the lawyers. The accused are placed inside iron cages within the court, and Rosi frequently frames their faces cropped by the bars.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast & Characters: ‘Poker Face’

It’s a marked contrast to Salvatore Giuliano’s first half. Here, the film settles, as Rosi becomes more “traditional” in his aesthetic strategies, focusing on shot/reverse-shot as he finds fewer reasons to leave the courtroom. It’s as if a period of history is ending in real-time, its depiction moving from active and complex to passive and simplified, in search of easily identifiable truths of “guilty” and “not guilty.”

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Burial’

Many of the best crime films make a virtue of the specificity of their location. Few, however, are as specific as Salvatore Giuliano, nor are they as cognizant of how the central locations effect the story. Salvatore Giuliano, both the film and the bandit, could not exist without the spectre of Sicily’s history behind it.

Fedor Tot (@redrightman) is a Yugoslav-born, Wales-raised freelance film critic and editor, specializing in the cinema of the ex-Yugoslav region. Beyond that, he also has an interest in film history, particularly in the way film as a business affects and decides the function of film as an art.

Salvatore Giuliano Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Call Me by Your Name’

Categories: 1960s, 2024 Film Essays, Crime, Crime Scene by Fedor Tot, Drama, Featured, Film, History, Movies

You must be logged in to post a comment.