Vague Visages’ The Blacklist essay contains spoilers for The Way We Were (1973), The Front (1976), Fellow Traveller (1990), Guilty by Suspicion (1991) and Dash and Lilly (1999). Check out VV’s film essays section for more movie and TV coverage.

Antipathy toward Hollywood is nothing new. Tinseltown has always been regarded as something alien in the American imagination — seductive but dangerous. As vociferously as the patriotism card was played by those patent-dodging outlaws who by sheer force of will were transmuted into moguls, the perception prevailed that the picture business was something distinct from traditional values. Classic Hollywood was seen by many as a haven for nonconformists of all stripes, harboring myriad militants and hedonists who used the allure of the screen to disseminate messages inimical to mainstream morality. American filmmaker Kenneth Anger tapped into this anxiety with scurrilous elan in his 1959 book Hollywood Babylon, which recounts lurid tales of debauchery whose questionable veracity is superseded by their confirmation of a collective suspicion. Much of what Anger recounts feels true, and that suffices to cement it into legend. The Catholic Legion of Decency shared a similarly florid view of the degeneracy that ran rampant among the movie crowd; it exerted substantial influence over the moral complexion of the pictures. The organization’s interventions ultimately led to the implementation of the Hay’s Code — the industry’s in-house regulatory effort; a signal to its critics that it could keep its house in order.

As the Cold War escalated, Hollywood’s politics came in for scrutiny. Those with industry power took pains to signal their loyalty and ostracize anyone whose ideological leanings could disrupt the pursuit of profit. The Committee for the First Amendment, which was formed by an assortment of Hollywood liberals in solidarity with their blacklisted brethren, quickly foundered amidst competing egos, self-serving equivocation and accusations of manipulation. This capitulation to the power of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was at odds with the notion of a liberal consensus dominating Hollywood; it revealed California’s conservative core, a stronghold in the schism between elites that Carl Oglesby outlines in his 1976 book The Yankee and Cowboy War — the political milieu which gave rise to Reagan and Nixon. In the 1970s, there was an attempt to address this period beyond the oblique treatment it received in the likes of High Noon (1952) and On the Waterfront (1954). It was integrated into Hollywood lore, as the industry loves nothing more than documenting its own triumphs and tragedies. The story of the blacklist offered not only an opportunity to issue an equivocal mea culpa, but also to lionize the creatives caught in the cultural crossfire. Those who stood firm and paid the price became the embodiment of Hollywood’s professed Weltanschauung — that for all the concessions in the face of realpolitik, the rank-and-file denizens of the picture business came away from this ugly period of history with their integrity intact. The reality is more complex; for all the betrayals by those in control, the bonds of the business were difficult to shake off entirely, and those who remained in the industry could never entirely condemn its treachery. Even the most cynical satire is half in love with the object of its barbs; there is a part of every constrained creative that loves their shackles and will make great play of rattling them.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Tightrope Walker: Dirk Bogarde’s Post-War Rebellion

Initially, it took the lightest genre to address the weightiest subject matter. For all its melodramatic trappings, The Way We Were (1973) belies the ideological struggle at its core. Katie Morosky (Barbra Streisand) is a college firebrand, president of the Young Communist League, who — despite her radicalism — falls for all-American boy and budding writer Hubbell Gardiner (Robert Redford). The protagonists’ relationship is viewed through multiple phases, as they grapple with fundamental differences in their perception of society. Katie voices her distaste for the “decadent and disgusting” profligacy with which Hubbell’s friends conduct themselves, but her class consciousness is bested by her physical attraction to the masculine ideal which this “nice gentile boy” embodies. Hubbell is content to glide by on the strength of his “all-American smile” — he is a symbol of the privilege which comes from comfort; the ease with which he navigates his personal ambition is contrasted with Katie’s combative posture against a world she sees as inherently unjust. Streisand’s character seeks refuge in political action, but her union with Hubbell accelerates the process of her becoming a New Deal reformer, who — like former U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt — believes capitalism can be saved from its worst excesses and leant a human face. Her political puritanism is dampened in the face of the erotic promise that attends the apolitical supremacy of Redford’s character, the carefree distance which permits him to scorn “political doubletalk.” Katie briefly sees a possibility of seeping into the fabric of American life under Hubbell’s wing.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Having It All: The Career Woman Takes Over

It is ultimately a hollow pact. When Hubbell’s novel is sold to the movies, he is content to settle into life as a Hollywood liberal, to use his work to promulgate a hazy conception of American decency. But the frontier is a snare, an outgrowth of the empire, a mirage in the desert which saps the will of well-meaning artists who are willing to slum it in the sun. However, Hubbell arrives at a time when such cowed intellectuals are about to be recast as “communist subversives,” to serve a barbaric form of political theatre. Redford’s character is compromised by his dalliance in the margins of the American wonderland; he is drawn into danger by the force of Katie’s militancy. As much as Hubbell would like to stay home and cave in to the new fear, the die has already been cast and his paymasters in the studio are all too willing to comply with power. The male protagonist learns that the war in which he fought never ended — it simply mutated and turned its gaze upon the imperial center. The “grown-up politics” Hubbell espouses can only conceive a reasonable outcome, in line with his experience at the heart of American life, but he no longer has the luxury of being neutral on a moving train, as Howard Zinn described it his 1994 book. He can no longer confront the world with a smirk, as life has become unbearably serious; the demands have become too heavy to condemn Katie’s “tantrums” in defense of her beliefs. Hubbell’s entanglements in radicalism teach him to bear the eternal burden of those on the Left and become “a very good loser,” as Katie describes herself. As Redford’s character settles back into an ersatz form of his previous ease, Streisand’s co-protagonist refuses to abandon her lost causes. Hubbell can only look upon Katie’s thankless devotion with bemused admiration. Romance may die, but ideology is a much more enduring force, and The Way We Were presents a cautionary tale on the dangers of political engagement.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Constructing a Madman: Lee Harvey Oswald’s Screen Life

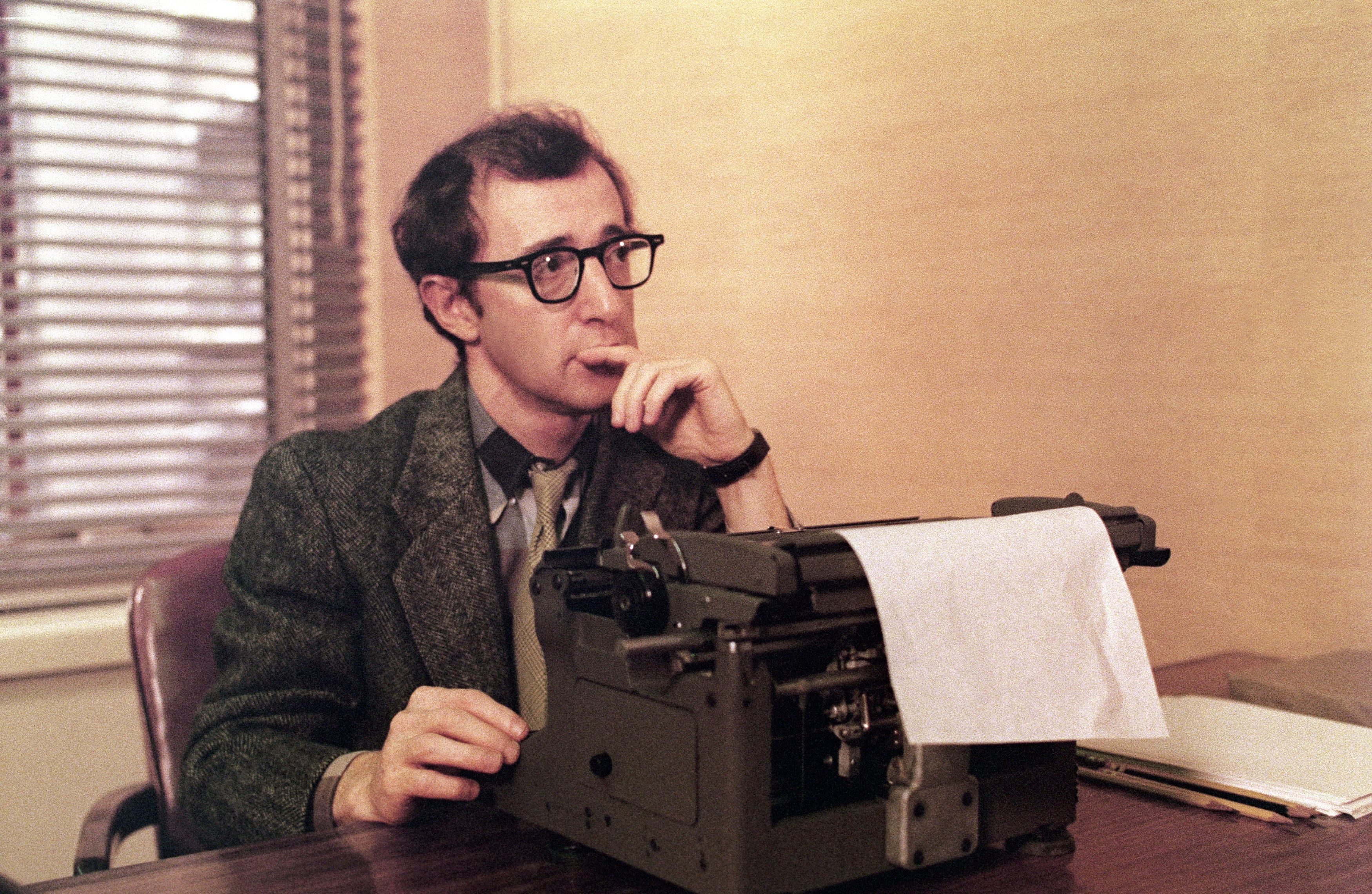

Examination of the blacklist was still restricted to so-called low genres like romance and comedy; the depredations of this period were placed within a more amiable framework, permitting the industry to individualize history and propagate the notion of a progressive Hollywood, exhibiting sympathy for the sinner without attacking the system. The Front (1976) uses the blacklist as a plot device in its paranoiac farce, which tells the story of cashier and inveterate gambler Howard Prince (Woody Allen), who agrees to act as a surrogate for a blacklisted TV writer, Alfred Miller (Michael Murphy), and soon builds up a cottage industry fronting for other blacklisted writers. Given that The Front was written by Walter Bernstein and directed by Matin Ritt — both of whom were blacklisted — it is surprisingly devoid of commentary, speaking perhaps to a squeamishness which persisted well into the 70s. Scant analysis is provided by Herbert Delaney (Lloyd Gough, also blacklisted), an avowed communist writer who tells Howard, “They’re trying to sell the Cold War, and they’re using the blacklist against anyone who won’t buy.” The soft power dynamic of show business is signaled in the film’s opening montage; a seemingly innocuous succession of images showing generals, politicians and film stars, yet speaking to the equivalence of these American icons. The Front is content to draw on the pathos of using blacklisted actors like Zero Mostel as TV-star-turned-reluctant-informant Hecky Brown; its anger is overlaid with a layer of sentimentality that often dulls its message — symbols suffice in the absence of a willingness to confront power.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Feeling Like a Winner: Elliott Gould’s Hollywood Hot Streak

As in The Way We Were, a steadfast radical sentiment is seen as something feminine and hysterical; it is a tendency to fall under the spell of romantic abstractions and let the heart lead. This is explored in the form of Florence Barrett (Andrea Marcovicci), a script editor at the TV station who is wowed by Howard’s scripts and believes him to be the very model of the socially conscious artist. When Hecky is fired for his subversive affiliations, Henry is exasperated to discover that Florence has quit her job in solidarity and intends to write a pamphlet that will blow the lid off the de facto blacklist in operation at the station. Her actions transform her into a wild-eyed malcontent, condemned to replenish the shelves of a radical bookstore with unread tomes. Again, there is a tension between male pragmatism and female fanaticism, but as The Front is an altogether more conciliatory piece, romance and politics coalesce to produce the desired outcome. Howard initially refuses to take up the historical mantle of defeat; he urges Alfred not to be “a loser all your life,” but when he is subpoenaed to testify before a HUAC executive session as a “friendly witness,” his refusal to provide a single name reframes defeat as freedom. A reactionary mob may be baying for his blood as he is carted off to jail, but Howard has won the admiration of those who share his distaste for the rigid ideological lockstep being enforced from on high. It is the fantasy of edifying persecution, placing the writer at the stoic center of a lesson only they possess the foresight and sensitivity to dispense.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — The Perennial Schmuck: Elaine May’s Disappointing Men

As the tumultuous 1970s came to an end, a boldness had asserted itself on the screen which reached its apotheosis with Reds (1981), Warren Beatty’s epic, audacious telling of the life of John Reed, the American journalist whose 1919 book Ten Days That Shook the World captured the October Revolution in Russia. It was no longer necessary to tiptoe around the political divisions which animated the blacklist using genre niceties, as a creative vanguard took the helm of an ailing industry and infused it with a new spirit of rebellion. The losers had seized the reins in a moment of crisis — they were heroic and cool, challenging the logic of Cold War soft power to which Hollywood had been content to hew in the 1950s and 1960s. It seemed as if the culture had changed decisively. But it was a false dawn, and the old animus fought back in the form of Ronald Reagan, who was about to be inaugurated as the U.S. president as Reds was released. The success of the film was less a vanguard than a valediction; the cold warriors were back in the ascendant throughout the 1980s, spinning new myths as the conflict entered its endgame. It wasn’t until victory was assured that Hollywood felt secure enough to assess the wreckage it left behind. As geopolitical exigency receded and America’s global hegemony was confirmed, the 1990s became a matter of making amends to those sacrificed in the fog of war.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Choose Death: Gregg Araki’s Apocalyptic 90s

This process began in earnest with Guilty by Suspicion (1991), Irwin Winkler’s account of the blacklist’s impact on director David Merrill (Robert De Niro), who returns to Hollywood from Paris to find himself embroiled in the town’s burgeoning paranoia. The protagonist is asked to testify before HUAC as a friendly witness, to get himself “straightened out” with the committee before he embarks on an ambitious new production for 20th Century Fox. When Merrill refuses to name names, his professional and personal life is plunged into turmoil as the FBI starts surveilling him and the work dries up. For De Niro’s character, it is a salutary insight into the power center that had been extant before his eyes, but one that he chose to ignore; he maintains the posture of the fundamentally apolitical creative whose youthful desire to help the needy during the Great Depression brought him into the orbit of the Communist Party. Merrill’s innocence is never in question; in the eyes of Winkler, this distinguishes him from fellow director Joe Lesser (Martin Scorsese), who states defiantly that he was and remains a communist, and is exiled for his unrepentant stance. Again, any kind of radical impulse is equated with a character flaw; Merrill’s lawyer, Felix Graff (Sam Wanamaker), tells him to explain to the committee that “I was young, I was foolish, I made a mistake, I was immature.” For the likes of Graff, to conceive of an alternative model for society is a disqualifying trait — something which must be “purged” from the hearts of the town’s denizens. Hollywood had internalized the borders of acceptable discourse, and its liberal core remained eager to stick within its confines. The Soviet threat was gone, and the excesses of HUAC were lamentable, but to be a communist was still considered beyond the pale in 90s Hollywood. Guilty by Suspicion reserves its sympathy for characters like Merrill, writer Bunny Baxter (George Wendt) and actor Dorothy Nolan (Patrica Wettig) — career-driven professionals whose artistic temperaments and bleeding hearts led them astray, contrasting them with the likes of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, executed as Soviet spies in 1953.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Visions of the Future from 1995: The World Is Screwed

To depict these characters as well-meaning liberals who were duped does a disservice to Hollywood’s radical past, unconsciously endorsing the HUAC line that an insidious plot was afoot to seed the mass media with subversive messages. For each side of the divide in Guilty by Suspicion, TV and film is understood as a peculiar form of enchantment that must be protected from malign influence — the theater is free to dabble with outré concepts, but the mass-produced image must remain pure, and those who produce those visuals must be responsible custodians of the public imagination. Hollywood and HUAC shared a keen awareness of the screen’s unprecedented power, but where HUAC sought to bring this into the light, Hollywood has always been chary of acknowledging its proximity to power, and Guilty by Suspicion takes pains to posit entertainment and politics as distinct domains. Studio head Darryl Zanuck (Ben Piazza) strains to maintain a scrupulous distance from “real life,” asserting that “nobody tells me how to make movies” and disdaining the fact that “someone running for Congress has a hard-on for Hollywood.” But he betrays the nature of the axis that oversees the flow of images with his reference to New York and Washington, the interests of finance and politics which imprint themselves on mass entertainment. As much as it may present itself as an escapist playground, Hollywood has always been amenable to the priorities of power — its personnel are there to weave the fables of empire; the star machine made propaganda to fight fascism, then was recalibrated for the war on the domestic front. Winkler conceives of this period as a beautiful tragedy, a time of heroic sacrifice, an aberration in which the glitzy parade of beauty and strength became entangled in the sordid business of politics. An interesting wrinkle is the presence of Larry Nolan (Chris Cooper), “a scared shitless loyal American” who, with echoes of director Elia Kazan, decides to name names and incurs the wrath of his peers. Here, the heroic veneer is momentarily punctured, revealing the frantic scrambling for self-preservation which the town inculcates. In 1999, Kazan was awarded with an honorary Oscar.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Recovery, Survival and Extinction: Abel Ferrara’s Exile Cycle

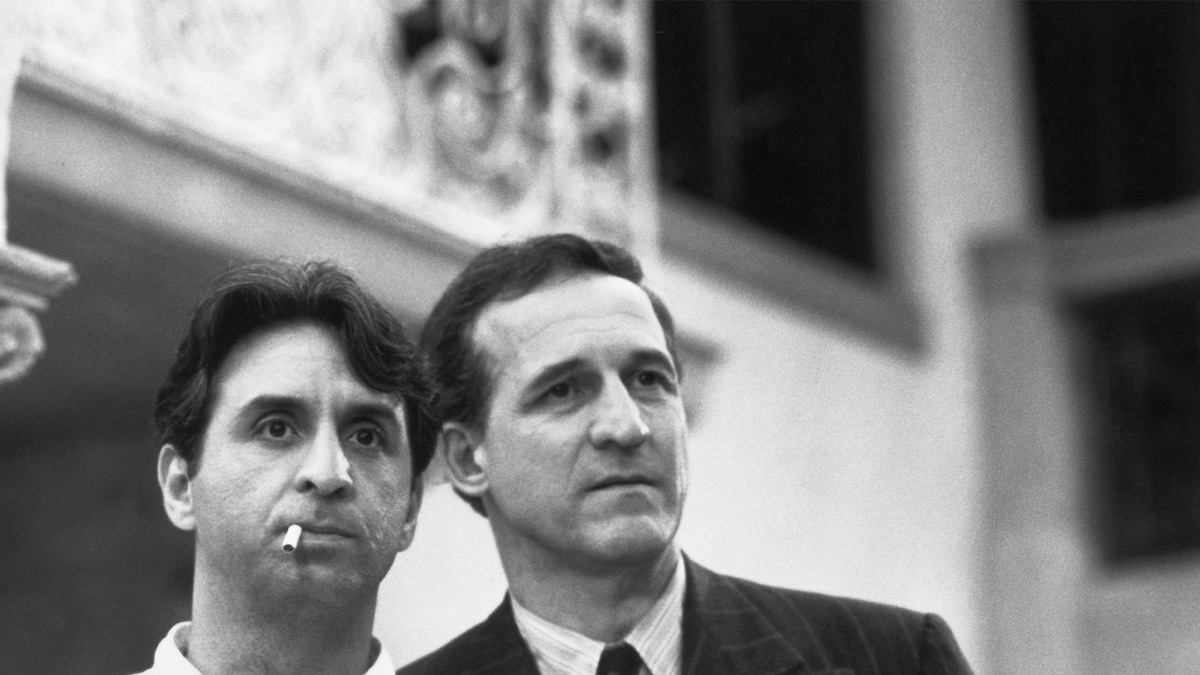

Charlie Chaplin’s battles with McCarthyism were detailed in Richard Attenborough’s 1992 biopic film, but the blacklist was largely relegated to TV in the 90s; cable delved into areas where cinema feared to tread. It was a historical madness which seemed so much more inexplicable in the age of third-way triangulation, but TV movies like Fellow Traveller (1990) set out to excavate the psychological landscape which thrust the likes of movie star Clifford Byrne (Hart Bochner) and screenwriter Asa Kaufman (Ron Silver) into the arms of danger. While exiled in London, Asa discovers that his friend and collaborator Clifford has committed suicide. Through flashbacks, it’s revealed that that Clifford was branded a “premature anti-fascist” due to his support for the Spanish cause, and was steadfast in his defense of America’s “Soviet allies,” whose “Red Army is saving civilization on the Stalingrad front.” But alliances shift, and one must move with them or be cast into the hostile waters of political realignment. In this climate of fear, symbols are constantly in flux, as Asa finds during his tenure as a peddler of “bourgeois fantasies for the toiling masses.” Studio notes instruct him: “Don’t smear the successful man; don’t smear the businessman,” calling to mind the restrictions imposed on the 1951 screen adaptation of Death of a Salesman for its criticism of capitalism. In Britain, Asa begins working on a children’s TV adaptation of Robin Hood, which requires him to temper the class dimension of the main character in favor of a more simplistic, heroic reading. Pompous director D’Arcy (Julian Fellowes) reminds him that “it’s not a bloody documentary.” A similar dichotomy is at play offscreen between the adherents of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud; Asa scorns psychoanalysis for its abandonment of “materialist analysis” in favor of “Freudian mystification,” yet he ultimately falls under the spell of Tinseltown shrink Jerry Leavy (Daniel J. Travanti), whose ministrations simply offer another avenue of control, a symbolic balm which sets out to paralyze dissent. Fellow Traveller presents a more realistic, less romantic picture of the creative caught up in the machinations of the witch hunt. Asa is not a victim of circumstance, but a conscious historical agent; he is wrapped up in the contentions of his time, willing to lose for a deeply held principle.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — The World Is Cold: Fallen Idols and False Prophets in Post-Crash America

Dash and Lilly (1999) is a somewhat facile account of the tempestuous relationship between writers Lillian Hellman (Judy Davis) and Dashiell Hammett (Sam Shephard), using romantic tropes to chart a course from the social upheavals of the 1930s to the narrowing political parameters of the 1950s. Dash and Lilly replicates the gender dynamic seen in The Way We Were and The Front — Hammett sees things in clear-eyed prose, while Hellman’s “theatrical reaction” to life makes her better suited to writing plays. The protagonists trade in lively banter like characters from one of Hammett’s hard-boiled yarns, heedless of the consequences as they lean into their perversity. Hellman introduces herself as a “failed poet, journalist and humorist,” while Hammett concedes he is “gambling, whoring, meaningless wisecracking, pissing-away-money drunk.”

The Blacklist Essay: Related — Follow That Dream: Generation X and Addiction Cinema

Dash and Lilly pitches ideological conviction as an outgrowth of emotion; the protagonists’ fidelity remains to each other as they traverse a world of lavish diversions in which even the politics seem unreal. Hammett and Hellman are trapped in thematic concerns, abandoning specifics in favor of a broader truth which expiates the guilt of their relative affluence as the world beyond their glamorous redoubt begins to unravel. It is only when the possibility of endless reinvention hits its limits that the forces of specificity make their demands, in the form of loyalty oaths which verify one’s status as “a good American.” Like so many blacklist dramas, Dash and Lilly dwells on those who were swept up in the blacklist — the broader injustice encompasses genuine radicals whose presence makes the business uneasy, foregrounding those with a reasonable claim to misguided liberalism signaled a minimal form of remorse. Hammett and Hellman are painted as hapless sybarites who shamble into ferment, whose modern mindset collides with the demands of intractable institutions, having to account for their instincts when the temper of the times changes. The ravages of McCarthyism continued to be assessed in films like The Majestic (2001), Good Night, and Good Luck. (2005) and Trumbo (2015). It was a beautiful tragedy that Hollywood would periodically re-stage in accordance with its mythology.

D.M. Palmer (@MrDMPalmer) is a writer based in Sheffield, UK. He has contributed to sites like HeyUGuys, The Shiznit, Sabotage Times, Roobla, Column F, The State of the Arts and Film Inquiry. He has a propensity to wax lyrical about Film Noir on the slightest provocation, which makes him a hit at parties. The detritus of his creative outpourings can be found at waxbarricades.wordpress.com.

The Blacklist Essay: Related — The American Horizon: Working Life in the New Hollywood

Categories: 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2025 Film Essays, 2025 TV Essays, Biography, Drama, Epic, Featured, Film, Historical Epic, History, Movies, Period Drama, Political Drama, Romance, Romantic Epic, Tragic Romance, TV

You must be logged in to post a comment.