Crime Scene is a monthly Vague Visages column about the relationship between crime cinema and movie locations. VV’s Lone Star essay contains spoilers. John Sayles’ 1996 film features Chris Cooper, Elizabeth Peña and Kris Kristofferson. Check out film essays, along with cast/character summaries, streaming guides and complete soundtrack song listings, at the home page.

*

John Sayles’ Lone Star (1996) is set in the town of Frontera, Rio County, Texas. The community is a fictional place, but its milieu is very real. Frontera is a border town, the crossing point into Mexico demarcated, as it always is in Texas, by the Rio Grande. In border towns, identities are mixed and complex; histories both local and national are defined not by the truth but by the loudest voices. There are a lot of characters who speak in Lone Star, and much of the story boils down to people remembering stories from decades prior as the protagonist, Sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), asks them what happened, once upon a time in America.

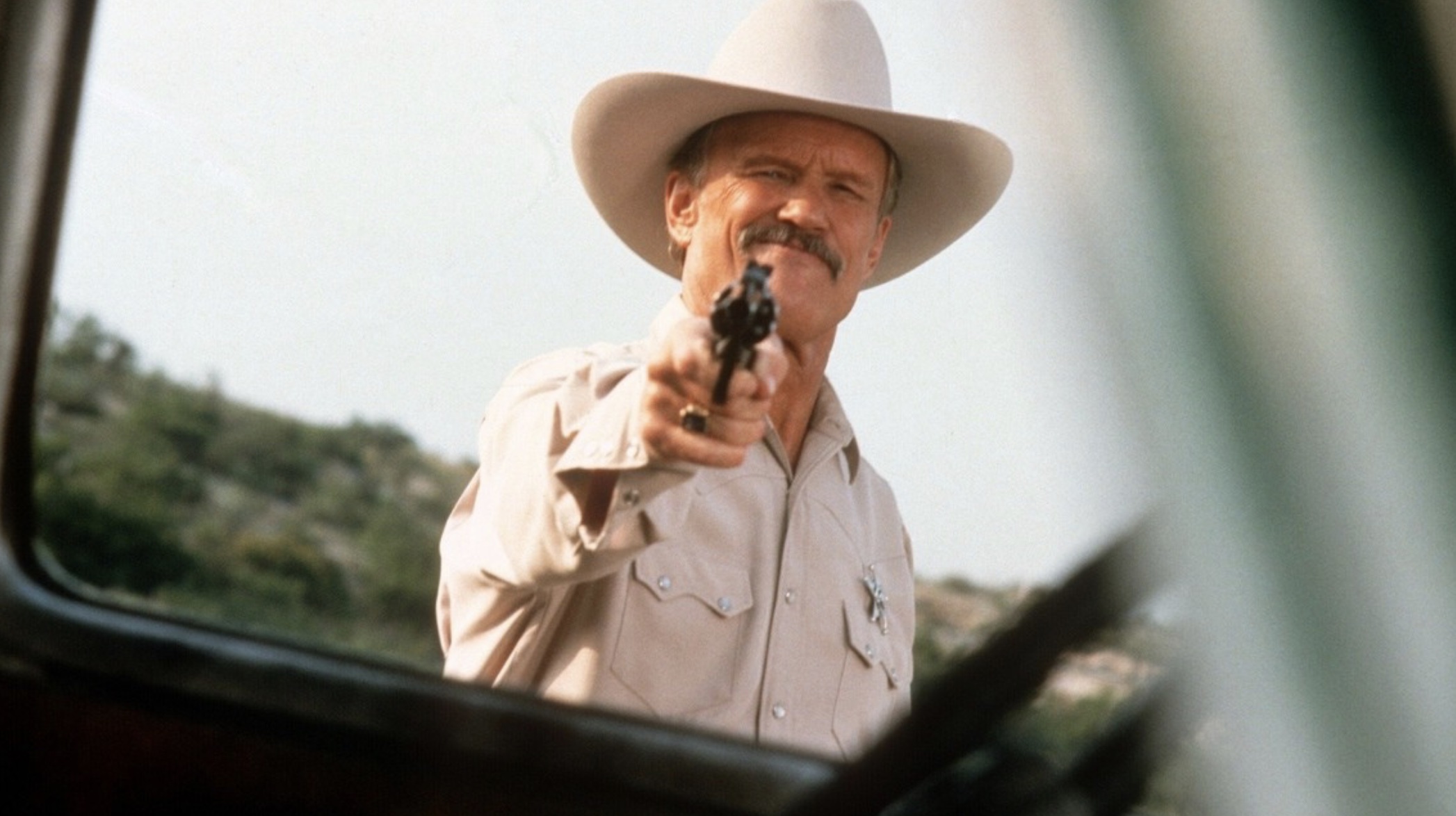

Lone Star’s plot ramps up when skeletal remains — alongside a Rio County Sheriff badge — are discovered by Sam outside of Frontera. The legend behind the town is well-known. Back in the 50s, Frontera was terrorized by Sheriff Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson), a tyrant who expected bribes and kickbacks over every piece of business or else trouble came calling. And Sam’s father, Buddy Deeds (Matthew McConaughey), stood up to the despised lawman (who eventually disappears). Most assumed Wade had been chased out of town or killed. Either way, the locals view the late sheriff as a hero who brought law, order and stability to the community. The discovery of the skeleton starts an investigation by Sam into Frontera’s history and mythos.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Massacre Time’

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” goes the famous line in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Lone Star might as well be a feature-length extrapolation of that line. Sayles’ most ostentatious gambit is to continually transition from past to present (or back again) within the same shot; as a protagonist recalls past events, the camera will drift across the room to a younger version of the character. It’s a physical, in-camera evocation of the idea that the past is always present. Although Frontera locals might do their best to forget, or tell their stories in such a way as to acquit themselves of guilt, the reality of the past always comes back.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Power of the Dog’

Sayles builds on this idea with the border town identity of Frontera and its residents, as various ethnicities co-exist in one way or the other. The river might provide a legal and natural border, but it is shallow and crossable on foot under cover of night (although still dangerous). Other figures Sam Deeds comes across tell stories of people-smuggling across the border as a daily occurrence. Today, we’re used to thinking of the Mexico-U.S. border as a militarized zone: even before Donald Trump’s insistence on a border wall, successive Democratic and Republican governments have invested billions in military technology for the sole purpose of keeping people out. Lone Star’s rendition of the border is low tech and, by modern standards, even genteel. A small sub-thread has Sam Deeds under pressure to come out in favor of a new jail being built for the town (it’ll bring jobs which are due to be lost because the U.S. army is closing down a nearby outpost, so the local politicians say). But crime is low in Frontera, and the jail is half-empty most of the time. Plus, there’s an inkling of the future militarization and criminalization to come. No point building jails if you don’t have criminals to put in them.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘1883’

Historically, border towns have a reputation for being seedy and dangerous wherever they are — places where people and goods mix. For reactionaries, nationalists and conservatives, the border is both the imaginary “true” heartland of a country and the place that requires the most stringent efforts to be homogenized, forever perceived as a threat by invasion from its neighbors. So it is with Texas — that most defiantly “American” of states whose iconography is steeped in cowboy mythology, manifest destiny and WASP-y self-sufficiency, despite it not becoming part of the USA until 1845 and despite the fact that some 40 percent of the population is Latino/Hispanic, with that percentage reaching the 90s near the border. The hard-right Republicanism of Trump and company is itself a reaction to a fear of fading influence. Sayles comments on this concept plenty in Lone Star, with minor characters left, right and center spouting anti-migrant rhetoric.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Harder They Fall’

In Lone Star, the white townfolk speak aplenty about being “replaced.” A parent-teacher meeting at the local school devolves into name-calling when angry, historically illiterate parents accuse a teacher named Pilar (Elizabeth Peña) of promoting a biased, anti-white history when her classes include a truthful, honest account of the complexities of life on the U.S.-Mexico border. The border is true “America,” which must be enforced and created. The only place where true “America” can be built is at the border. Some Mexican-born Americans internalize this philosophy: Elizabeth’s mother, Mercedes (Míriam Colón), runs a restaurant staffed largely by undocumented migrants, but she refuses to speak Spanish and is happy to call the police whenever she witnesses illegal crossings near her villa. These contradictions go unanswered within Lone Star because they can’t truly be answered: people will take any excuse to absolve themselves of guilt or face the cognitive dissonance. Maybe it’s part of border life.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Know the Cast & Characters: ‘1923’

Behind this are the two figures of Charlie Wade and Buddy Deeds, the two sheriffs whose backstories dominate and shape Frontera’s history. Wade is ever-present in flashback sequences, and Kristofferson imbues his character with menace and malicious authority. Buddy appears only a handful of times, with a youthful McConaughey demonstrating his then-rising star power. Wade is an obvious tyrant, the sort who clearly needs to be put to justice, and as Sam talks to folks old enough to remember Kristofferson’s character, it’s evident that nobody misses him. But as Cooper’s protagonist finds out more about his father, Buddy, it’s clear that he was no saint either. Yet, the townsfolk idolize him, willing to look the other way when it came to his own sins, simply because he “kept the peace” better than any sheriff before or since. It’s a peace that threatens to quickly come undone with Buddy’s passing, like a captain building a boat only he knows how to sail. Sam’s investigation into his father is an oedipal reckoning — one that seeps into the local geography and Frontera’s history. He’s like Tito, the president of socialist Yugoslavia and the leader of a country that was hugely revered and massively respected, but whose passing left a deep void which nobody was able to fill, leading to collapse and destruction.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre’

Are such figures a historical necessity? Deposing a tyrant is one thing, but do they need to be followed by stabilizing figures who nevertheless deploy equally illiberal tactics albeit to more humane ends? Buddy Deeds is an Americanizing, civilizing influence in Lone Star. But for the long-term health of Frontera, is that a good thing?

Lone Star Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Calamity Jane’

The genius of Sayles’ Lone Star is that the film envelops its difficult, knotty questions about history, identity and geography without any didacticism. “Who am I?” is an open-ended question, and even its seemingly more binary cousin “Where are you from?,” often posed with an undertow of hostility, has no direct answer for many. Lone Star looks again to the Rio Grande river. It is a physical place, shaped and enforced by violence. But animals and people can still cross it if they wish; waters ebb and flow, and the banks change. Nothing stays the same, no matter how much people desperately try to keep it that way.

A new 4K restoration of Lone Star will premiere at Cinema Rediscovered (Bristol) on July 25, 2024 before releasing in UK cinemas on August 16 via Park Circus.

Fedor Tot (@redrightman) is a Yugoslav-born, Wales-raised freelance film critic and editor, specializing in the cinema of the ex-Yugoslav region. Beyond that, he also has an interest in film history, particularly in the way film as a business affects and decides the function of film as an art.

Lone Star Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Iron Claw’

Categories: 1990s, 2024 Film Essays, Crime Scene by Fedor Tot, Drama, Featured, Film, Movies, Mystery, Western

You must be logged in to post a comment.