Krampus, released in 2015 by the director of the cult Halloween anthology Trick ‘r Treat, earned more than a modest takeaway in its opening weekend ($42.7 million with a $15 million budget) and seemed to completely fall off the radar shortly after hitting theaters. Perhaps it’s the fact that, with a cast including the likes of Adam Scott, David Koechner and Conchata Ferrell, and a trailer during which the first half frames comedic aspects of the film against a light-hearted Christmas jingle, audiences came into it assuming a slightly lighter, funnier take on Christmas horror. To be met with such grisly hopelessness unquestionably dampened expectations for some (at least, that’s what happened for this writer the first time around). Or maybe it was the draw-in of familiar faces against the nature of the horror itself, which includes a young girl being swallowed alive by a monstrous jack-in-the-box, a baby being kidnapped by a demon elf and a brief animated sequence where a young girl listens to her family being murdered by fantasy ghouls. But whatever the case may be as to why Krampus slipped to the cinematic wayside in the past few years, it remains understated Christmas horror in its sharp, gruesome glory.

The tension between the two families — at first comical in the easy target that is the gun-toting, Hummer-fucking, camo-donning, Mountain Dew-gargling caricature of Linda’s side of the gene pool — is caused largely by discrepancies in class (Sarah’s family lives in a large, suburban domicile, and Aunt Dorothy lives in a trailer). There is also a strain within Max’s immediate family dynamic as well, brought about by his own misbehavior, his older sister’s burgeoning departure from her adolescence and the growing distance between Tom and Sarah. This overwhelming absence of family togetherness and Christmas cheer is the root of Max’s faltering faith, and the very cause for the eventual horrors inflicted upon them all.

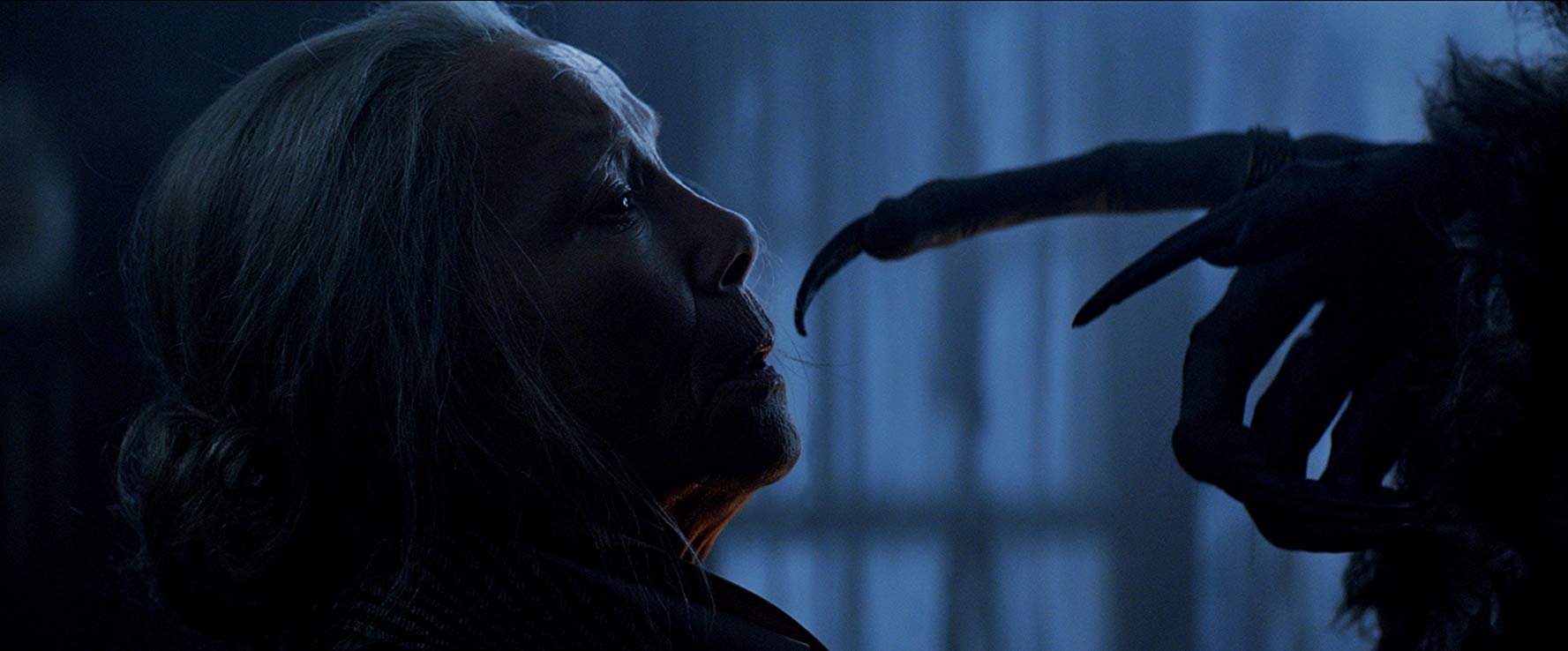

No, the root problem with Christmas is the very nature of Christmas itself, fomented by greed and the forcing together of families that do not belong. For many, Christmas is a chore, not a respite, and thus the holiday becomes an amalgamation of festering negativity. “Krampus came not to reward, but to punish,” Max’s grandmother, Omi, asserts forebodingly to them all, as it becomes clearer that the pitter-patter upon the rooftop and the snowstorm ripping through the neighborhood outside are not signs of good tidings, but of their very reckoning. The families’ eventual coming-together as the film pushes on through horror after unimaginable horror is brought about only by their mutual agony and struggle for survival against an outside threat — without it, they would have continued on suffering through each other’s very proximity to one another.

Krampus merely laughs at Max’s desperate appeal for the return of his family, and the return of the Christmas he thought he once knew, before pushing the boy into a pit of fire. From this, Max awakens to find himself back in his bed, unharmed, on Christmas morning. He descends down the stairs to the living room, where he finds his two families together — finally — smiling, laughing, awaiting his arrival. Max’s face splits with joy as he joins Tom and Sarah on the couch to open his goodies, embracing the safety of his returned family, soaking in the sheer relief that the previous night’s events were all just a horrible nightmare, and understanding that he will never take their existence for granted ever again.

This is what Christmas is, this is what family is, and this is what Krampus leaves viewers with. The end result of Max’s fate is the same result for many others, and what would’ve been the result even if Krampus hadn’t come a-knocking. The fate of family is inescapable, and so is the fate of all future Christmases. We are all trapped by the unreturnable gift of our lineage, and by the chokehold that the season has on both us and our culture. We will continue to host and to visit our insufferable relatives for Christmas dinner; we will continue to pretend everything is fine despite shouting matches or a suspicious lack thereof. There will be a candy veneer of forced pleasantness coating innards of the truth. Max did finally get what he wished for — a Christmas with his family to mirror the happier ones of the past — but in the end, it is clear that they are far worse off because of it.

Krampus is the pinnacle anti-Christmas movie in the way it thrives on the sheer awfulness of the holiday. It is ugly, it is unpleasant, and it is still utterly festive in the fact that it embraces the nature of the season as it has always been. If you are looking for a little Christmas cheer, then maybe Krampus isn’t the movie for you. But if you like ugly truths of reality to complement a bit of your cranberry sauce, it couldn’t come more highly recommended.

Brianna Zigler (@briannazigs) is a freelance film journalist based in the suburbs of Philadelphia. She is staff writer for Screen Queens and contributor for Film Inquiry, with bylines in Reel Honey Mag and Much Ado About Cinema. She loves horror and her pet parrot.

Categories: 2018 Film Essays, Featured, Film Essays

3 replies »