Writing just before the turn of the 20th century, black intellectual W.E.B. DuBois coined the term “double consciousness” to describe the African-American experience of living in the United States. He described his own experience, and by extension, other black members of American society, as a constant negotiation with bifurcation, both self-imposed and foisted upon him by external circumstances. He wrote, “One ever feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

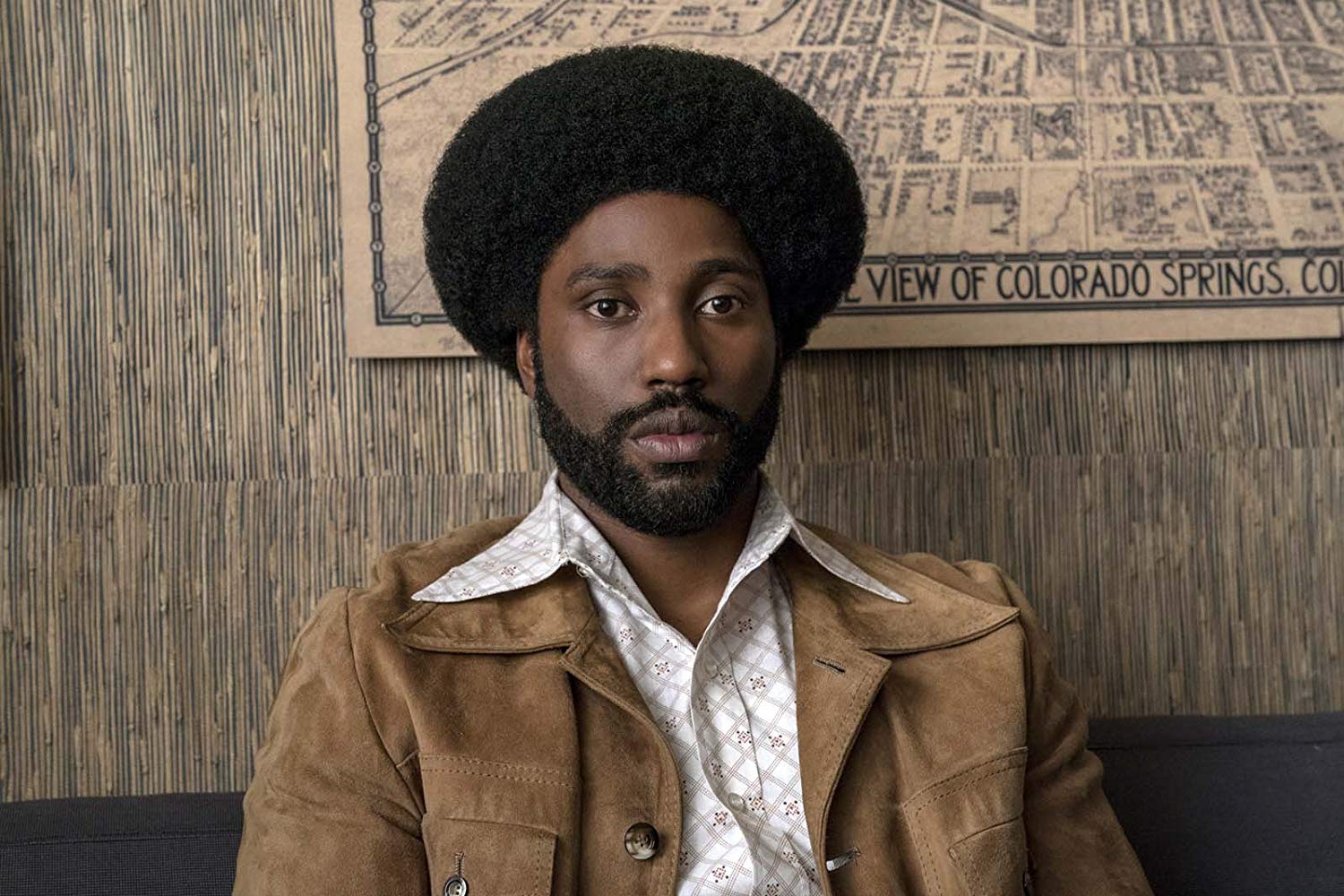

Spike Lee’s film BlacKkKlansman, released some 120-plus years later, is preoccupied with this perpetual state of “two-ness.” The storied filmmaker is nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director for the first time in his 35-year career for the based-on-a-true-story film, which follows Colorado Springs police detective Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) and his partner Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) as they investigate the activities of circa-1970s Ku Klux Klan members. Double-consciousness is built directly into the premise of the film; Ron talks with the Klan members over the phone, while Flip, using Stallworth’s name, plays the role in person, attending Klan meetings and embedding with the chapter on a shared undercover assignment. The movie’s plot follows the investigation, while Ron romances the radical president of the local college’s black student union, Patrice (Laura Harrier), balancing his divided self between his roles as police officer and devotee of the Black Power cause, and talks on the phone with the Klan’s Grand Wizard, David Duke (Topher Grace) while pretending to be white.

Upon its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 2018 and its subsequent stateside release in August, BlacKkKlansman was written about as something of a “return-to-form” for Lee, who has spent the last several years making smaller films — Red Hook Summer (2012) and Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (2014) — or films rightly or wrongly seen as misfires — Oldboy (2013) and Chi-Raq (2016). Regardless of the perceived worth of any of those recent projects, Lee doubtless seems invigorated by the subject matter of BlacKkKlansman, which allows him to practice a little double consciousness of his own. Though the film’s setting is unquestionably the mid-1970s — an aesthetic Lee seems excited to revisit 20 years after his underrated 1999 film Summer of Sam — the director intentionally litters BlacKkKlansman with overt reflections of the year of its production. The film distorts the past through the refracted lens of the present, collapsing the distance between then and now in ways designed to provoke the audience as only Lee can.

As a filmmaker, Lee is stylistically inventive, muscles he flexed from his earliest works, She’s Gotta Have It (1985) and School Daze (1988). His direction of Do the Right Thing is adventurous and provocative. He shoots the block in as many colors as he can capture. His camera oscillates between handheld, guerrilla-style cinematography and highly choreographed, balletic moves. His actors address the camera in highly performative, Brechtian assaults on the image itself, in one sequence hurling a series of racial epithets directly at the audience through the lens. From there, Lee developed a crucial series of directorial signatures, including a rolling camera shot in which actors appear to float through the space as the background moves around them. Each of his films following Do the Right Thing feel like they are made by a director who knows exactly how to use images to carry ideas about character, narrative, theme and — crucially for Lee — politics.

One might expect the direction for BlacKkKlansman to lean on Lee’s ostentatious, enunciative style, but it is often remarkably restrained. Shooting in widescreen, Lee uses the first third of the film to emphasize Ron’s isolation. He is the first and only black officer on the Colorado Springs police force, which Lee visualizes by consistently placing Ron in the center of otherwise empty medium shots. In his first interview with Chief Bridges (Robert John Burke) and Mr. Turrentine (Isaiah Whitlock, Jr.), his questioners are shot together in two-shot, while Ron is alone. He generally remains so until he jokingly responds to an advertisement for the Klan by calling the listed phone number out of boredom. Lee shoots Ron alone at his desk in the officers’ bullpen while he spouts racist nonsense at the Klan member on the other end of then line. In the reverse shot, Lee stays wide, the white detectives turning around in their swivel-chairs to stare at Ron’s inflammatory language. In this visual strategy, Lee begins to emphasize Ron’s navigation through one of his many double consciousnesses; he must reconcile his role as an individual black man, so often a victim of police abuses of power, with his other role as a member of that larger institution. He is both the oppressed and the oppressor.

Lee changes tactics when the investigation begins and Ron has bisected his own identity into himself, on the phone, and Flip, in person with the Klan. Lee matches the growing partnership between the two men by increasingly shooting them in two-shot. In their many meetings with supervisors in the department, they are framed together, while their boss is framed alone. In aligning Ron and Flip visually, Lee expresses their growing understanding of one another. Flip bears Ron no ill will. This is no “racist-learns-to-see-the-humanity-in-us-all” story. In fact, in an echo of a scene from Do the Right Thing, Flip says all his popular culture heroes are black. In Lee’s earlier film, he used a similar moment for his character, Mookie, to point out the hypocrisy of Italian-American Pino (John Turturro), who bears racist ideas while idolizing black cultural figures. Unlike Pino, Flip’s sin is not racism, but indifference; he just doesn’t think much about people’s identities, including his own. As he leaves the locker room after a scene when he and Ron impersonate one another to match their voices, he casually mentions that he is Jewish. As he becomes embedded deeper within the Klan’s membership, and is witness to and participant in a collection of racist and anti-Semitic diatribes, Flip recognizes the importance of his own identity. He sits on the edge of a desk with Ron, staring down at the Klan membership card that bears the name they now share, and says, “I never used to think about this Jewish stuff. Now I think about it all the time.” In two-shot, the partners sit back-to-back, joined by their otherness in the shadow of a culture that has rejected them for hundreds of years.

The other cinematic preoccupation that drives BlacKkKlansman is Lee’s engagement with the blaxploitation genre, which he has heretofore avoided. Dominated by 1970s films like Shaft (1971), Superfly (1972), Coffy (1973) and Cleopatra Jones (1973), all of which are name-checked in the film in a conversation between Ron and Patrice, the blaxploitation genre often served as a vehicle for black filmmakers to stage revenge fantasies against the dominant white culture. The black heroes and heroines of these films often did battle against corrupt (white) police officers and Italian Mafiosi, against whom they always came out on top, and looked and sounded cool while they did it. Lee’s contemporary Quentin Tarantino, a blaxploitation-obsessive with whom Lee has clashed over the latter’s liberal use of the n-word in his scripts, picks up on this revenge fantasy most clearly in his own 2013 film Django Unchained. Its blood-soaked conclusion, in which escaped slave-turned-avenging angel Django (Jamie Foxx) blows away a house full of white racists and slaveowners, is very satisfying to watch, just as the early blaxploitation films were. It is hard to say, however, that any of Lee’s films ends as satisfyingly. In his world, wrongs often go un-righted, justice is rarely served. In BlacKkKlansman, when the musical score, the costuming, the setting and the genre conventions signal blaxploitation, Lee uses it to create a fake-out. The climactic moment of the film occurs when several of the most disgustingly violent and extreme members of the Klan’s chapter are blown up by their own bomb in a botched attempt to kill Patrice; in its epilogue, Flip, Patrice and Ron all work together to get Landers to admit, on tape, that he not only pulled over and harassed Patrice during the traffic stop, but also shot and killed an unarmed black man the previous year, and he is hauled away in cuffs by an enthusiastic Bridges who seems eager to prosecute him. Finally, Ron and the other cops humiliate Duke over the phone when Ron confesses he is black, leaving the Grand Wizard flummoxed. He settles down into a nice dinner with Patrice, and all seems well.

These individual victories do not stem the larger tide of injustice. Lee finally uses his signature floating shot for Patrice and Ron, pulled down the hallway of Ron’s apartment building, guns drawn, as they investigate a suspicious noise outside. Lee then cuts to what they see: a burning cross, surrounded by hooded members of the Klan. They have not been defeated by Ron’s investigation, but emboldened. Lee denies the head-nodding resolution that characterizes many of the films of the blaxploitation genre, including Tarantino’s in Django Unchained, as Django and his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) ride off into the sunrise after burning the plantation to the ground and killing all of its slave-owning residents and enablers. This speaks to Lee’s historical avoidance of the blaxploitation genre; he would never be capable of offering such an ending and suggesting that his protagonists’ lives were about to get much better. Lee is much more interested in waging an assault on the perpetual racism of American institutions, a goal in tension with resolving characters’ problems just before the credits roll.

BlacKkKlansman, fairly or not, will be judged as Lee’s “comeback” movie. He never really left, of course. That’s evident in the film’s most astonishing sequence, in which Flip is inducted into the Klan by Duke, while Ron watches from a hidden vantage point. Lee audaciously intercuts the scene with a group of young black activists, led by Patrice, who have gathered to hear civil rights leader Jerome Turner (played by actor and civil rights icon Harry Belafonte) relay a story about a young man who was convicted of raping a white woman by an all-white southern jury, and then beaten, murdered and mutilated by a lynch mob while Turner watched from concealment. Lee deftly parallels Ron’s hiding place (a small window in an attic) with Turner’s (also a small window), making them both witnesses to horror. As Turner recounts the horrible assault on the young man, Lee cuts back to the Klan members donning their hoods and listening to Duke’s white power propaganda. The scene gets much uglier as the members’ wives are brought in and they join together in watching a film print of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of A Nation (1915), hooting racist epithets at the screen and laughing like hyenas as a Black man is lynched by the Klan, the film’s heroes. Most daringly, Lee ends the sequence with Duke and his fellow Klan members shouting “White power!” over and over again, and then cuts to Turner’s audience shouting “Black power!” He’s far out on a limb here, risking a misinterpretation of this sequence by an audience preternaturally dispositioned to blame “both sides.” In fact, this is Lee’s rejoinder to the contention that “both sides” had “some very fine people.” He is not aligning the white power-driven Klan members, who cheer vigilante murder and mock people based on their skin color, with the black power activists who rise up in defense of their own bodies. His intercutting between the two groups emphasizes their differences, making the case for the legitimacy of the Black Power movement while undermining the illegitimacy of the Klan’s pursuit of white supremacy.

At the core of BlacKkKlansman is an effort to point out the absurdity of the kind of white victimhood practiced by the Klan’s members and leaders like Duke. As Ron races to stop the Klan’s attempted assassination of Patrice, carried out in the name of white supremacy, Duke speaks on the soundtrack about America, which he insists is a racist country — against white people. Lee, a master of redeploying the images of cinema’s past — an impulse he showed in the staggering conclusion to Bamboozled, in which a compiled reel of images of performers in blackface puts the film’s violence in new perspective — uses BlacKkKlansman’s images to expose how white filmmakers have appropriated the suffering of black people to tell their own stories. Lee’s very first shot is so bold, it’s not even his own. He opens with a lifted image from 1939’s Gone with the Wind; it’s the famous shot that cranes back over a field of wounded and dying Confederate Army soldiers, the music soaring as the camera takes in the awesome sight of so many men who have sacrificed for the cause. Lee’s contempt for that cause is the subject of BlacKkKlansman, and his goal in concluding the film with a tribute to Heather Heyer, the young white activist who lost her life in Charlottesville when a white supremacist slammed his car into a crowd of protestors, is to argue that some causes are just, and some are not. The Confederacy’s was not. The Klan’s is not. The Charlottesville “blood-and-soil” boys’ cause is not. Ron and Patrice have a just cause. Heyer had a just cause. The same applies to Lee. To know the difference is to understand both the right and wrong of America’s past and its present. To know the difference is to choose to walk towards the light while knowing the darkness follows close behind.

Brian Brems (@BrianBrems) is an Assistant Professor of English and Film at the College of DuPage, a large two-year institution located in the western Chicago suburbs. He has a Master’s Degree from Northern Illinois University in English with a Film & Literature concentration. He has a wife, Genna, and two dogs, Bowie and Iggy.

Categories: 2019 Film Essays, Featured, Film Essays

You must be logged in to post a comment.