How do you capture the experience of being black in America in a single curated collection of films? All that beauty, pain and complexity shrunk down to merely a series of cinematic experiences? FilmStruck makes an honorable attempt in their “Black in America” collection. The title is both too curt and too expansive (perhaps it was chosen for marketing reasons) to reflect the actuality of what they gathered, as it hones in on a specific period — before, during and after the Civil Rights Movement — which ultimately cannot stand in for the entirety of the black experience in the United States.

The standout films in the series are the ones that seem to have been added as an afterthought. In his introduction to the “Black in America” bundle, FilmStruck host Malcolm Mays notes that the series focuses on the black experience in the South. Yet two films, Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground (1982) and Charles Burnett’s My Brother’s Wedding (1983), take place well outside the region — in New York and Chicago, specifically. In what is likely not a coincidence, these are the only two films in the collection to depict black life from the perspective of black filmmakers. Neither is included in Mays’ introduction to the film set. It does not appear that these were included in the original plan for the series, and it would have suffered tremendously without them.

Losing Ground is the first known feature-length film directed by a black woman, paving the way for Julie Dash, Dee Rees, Ava DuVernay and more. The site’s description mentions that the film is “groundbreaking” but does not specify this is the reason why. Burnett, meanwhile, made My Brother’s Wedding a year later for a mere $80,000 because he refused to make movies that fit into a more sensational, stereotypical portrayal of black Americans as seen in Blaxploitation. There was not a well-established system in place to distribute or exhibit movies that presented black life on its own mundane, commonplace terms rather than in relation to white Americans or the government. As such, both films lingered in obscurity for years, only receiving theatrical releases in the last decade.

It’s a shame that FilmStruck didn’t devote the energy to explaining why these films are different from the rest of the series — or, better yet, connect the dots between how the racism shown in the other five films contributed to the environment that starved Losing Ground and My Brother’s Wedding of a deserving audience. The service has invested in creating original content to accompany these bundles like a video essay by Every Frame a Painting’s Tony Zhou for their Howard Hawks series and a sit-down with scholars like Annette Insdorf to break down opening scenes of classic films. This collection really could have used some additional material to place the films in a proper historical context.

That’s not to say that the “Black in America” series is not without its surprises and delights. As a budding rep rat in New York, I’m enjoying taking in older titles in curated sidebars — but timing has yet to allow me to see all the titles in a given series. An incredible benefit of FilmStruck is that it allows cinephiles across America to set their own schedules to consume an entire repertory series as they please. From there, it becomes a much easier proposition to tease out curatorial intent and interrogate the connections between programmed films.

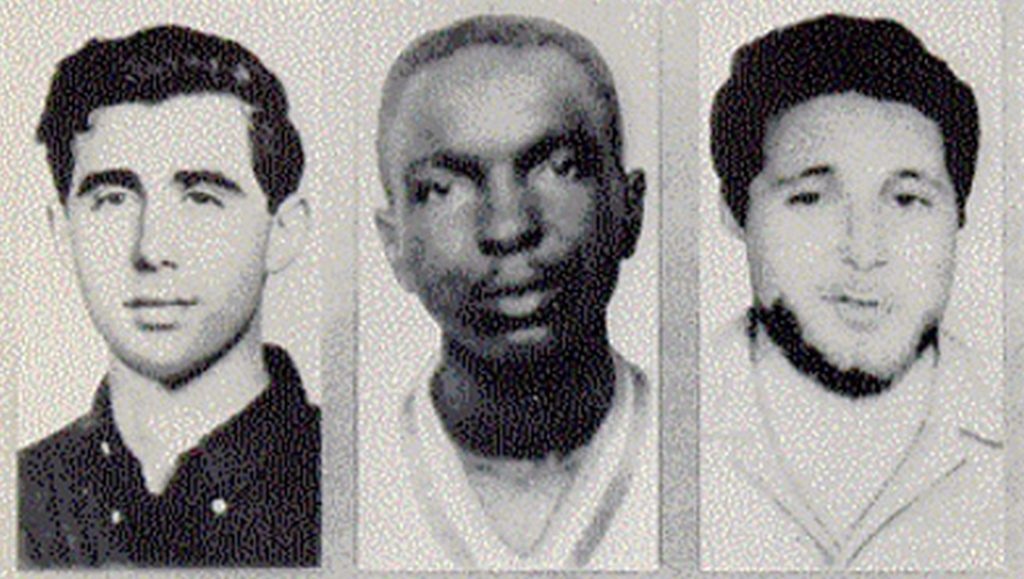

The most fascinating inclusion in the set is 1964’s Black Like Me, a now-notorious film adaptation of journalist John Howard Griffin’s account of donning blackface to understand the plight of black Americans. It should go without saying that the film is now extremely dated; at times, it’s truly cringe-worthy. The concept itself is shudder-inducing. Why does a white person need to don the guise of black skin to understand and feel the pain of his black countrymen? Is it not enough to simply listen and trust them? Don’t even get me started on how every black person in the film seems unable to sniff out James Whitmore’s John Finley Horton (a stand-in for Griffin) as the wannabe Rachel Dolezal of his day. The film reduces racial identity to mere skin color, ignoring that having a racial consciousness in America entails a lifetime of accumulated experiences involving dehumanization and degradation.

And yet I wager that studying Black Like Me would make for the most illuminating experience out of any of the seven films in the “Black in America” collection. I’m glad FilmStruck included it, warts and all, rather than limiting the series to only films that match our present-day standards for acceptable storytelling about race. When we mistakenly buy into the concept that we’ve reached the end of history, that society will never become more advanced than it is right now, we impede the necessary progress. Unless you look at the dumpster fire of the world and somehow see a utopia, society should continue to evolve and change. By analyzing how the misplaced white guilt of Black Like Me ultimately fails and belittles the people it seeks to help, we can hopefully gain the critical skills to apply the same framework to contemporary entertainment.

With the exception of Lionel Rogosin’s Black Roots (1970), which takes a Direct Cinema approach to allow black artists to share the joys and pains of their life experiences, the remaining films all subscribe to a triumphalist narrative about race in America. I’ll single out 2008’s Neshoba: The Price of Freedom as a particularly relevant watch. Directors Micki Dickoff and Tony Pagano return to the site of the Mississippi Burning murders as the town wrestles with the retrial of a now-elderly killer. Beyond serving as a sad reminder of how many attitudes about race don’t change, it also serves as a testament to just how much the racial equality of blacks in America relies on white people. (1985’s You Got to Move, on the other hand, is a rather quaintly told account of achieving social change through the power of individual actions.)

A visit to 1974’s landmark TV movie The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pitman is also worthwhile, and not only to marvel at the regal Cicely Tyson — still churning out great performances at 93! As Roger Ebert put it, “Look at a movie that a lot of people love, and you will find something profound, no matter how silly the film may seem.” It’s instructive to consider what made this story connect with audiences four decades ago and wonder what has changed in the way we treat stories of the black experience in America.

This piece concludes my #FilmStruckFebruary series. I hope you’ve enjoyed following along or reading pieces here and there! By my own measures of success, I think I achieved what I hoped from this month-long journey. I strayed off the beaten Criterion Collection path, expanded my canon, considered the intentions behind FilmStruck’s programming and took the time to sharpen my appreciation of films through bonus features.

In case you don’t believe me, check out my full monthly viewing syllabus for yourself! (And please, please, watch Clio Barnard’s The Arbor.)

February 1: The Long Day Closes (Terence Davies, 1992)

February 2: Gap-Toothed Women (Les Blank, 1987)

February 3: A Dog’s Life (Charlie Chaplin, 1918)

February 4: Desert Hearts (Donnna Dietsch, 1985) + bonus material for Desert Hearts

February 5: The Earrings of Madame de… (Max Ophüls, 1953)

February 6: Bonus material for The Earrings of Madame de…

February 7: Mur Murs (Agnès Varda, 1980)

February 8: Manhattan (Paul Strand and Charles Scheeler, 1921), N.Y., N.Y. (Francis Thompson, 1957), Bridges-Go-Round (Shirley Clarke, 1958)

February 9: Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934)

February 10: Fallen Angels (Kar-Wai Wong, 1995)

February 11: The Arbor (Cleo Barnard, 2010)

February 12: Adventures in Moviegoing with Guillermo del Toro (FilmStruck Original)

February 13: Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist (Saul J. Turell, 1979) + bonus material for Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist

February 14: The Emperor Jones (Dudley Murphy, 1933)

February 15: Black Panthers (Agnès Varda, 1985)

February 16: Black Roots (Lionel Rogosin, 1970)

February 17: The Black Balloon (Benny Safdie, Josh Safdie, 2012)

February 18: The Silence (Ingmar Bergman, 1963) + bonus material for The Silence

February 19: Bonus material for Winter Light (Bergman, 1963) and Through a Glass Darkly (Bergman, 1961)

February 20: Neshoba (Mickey Dickoff and Tony Pagano, 2008)

February 21: Bonus material for Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, 2012)

February 22: Black Like Me (Carl Lerner, 1964)

February 23: You Got to Move (Lucy Massie Phenix and Veronica Selver, 1985)

February 24: Losing Ground (Kathleen Collins, 1982)

February 25: The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (John Korty, 1974), My Brother’s Wedding (Chalres Burnett, 1983)

February 26: Skyscraper (Shirley Clarke, 1960)

February 27: Jezebel (William Wyler, 1938)

February 28: The Man Who Knew Too Much (Alfred Hitchcock, 1934)

Watch the ‘Black in America’ collection and Marshall’s #FilmStruckFebruary titles at FilmStruck.

Follow Marshall Shaffer on Twitter (@media_marshall).

Categories: 2018 Film Essays, Film Essays, Vague Visages Is FilmStruck

You must be logged in to post a comment.