Vague Visages’ Tokyo Uber Blues review contains minor spoilers. Taku Aoyagi’s 2021 documentary features himself, Kazuki Iimuro and Tsuchi Kanô. Check out the VV home page for more film reviews.

In recent years, there’s not been a shortage of films shining a light on the gig economy and the desperate living/working conditions it forces people into. At one point in Taku Aoyagi’s documentary Tokyo Uber Blues, the then-twenty something filmmaker — having just relocated to Japan’s capital as the COVID-19 lockdown began — is shown an interview with British director Ken Loach discussing these very conditions which formed the backdrop for his 2019 drama Sorry We Missed You. Drunk and crashing at a friend’s house, Aoyagi inarticulately expresses that Loach’s insights are revelatory for him, having never considered the ways in which Uber Eats exploits worker’s labor. It’s the first of many moments in the documentary that feel reverse-engineered, if not staged. Why would the filmmaker even be documenting his experiences on the job if he weren’t aware of the precarious material conditions going in?

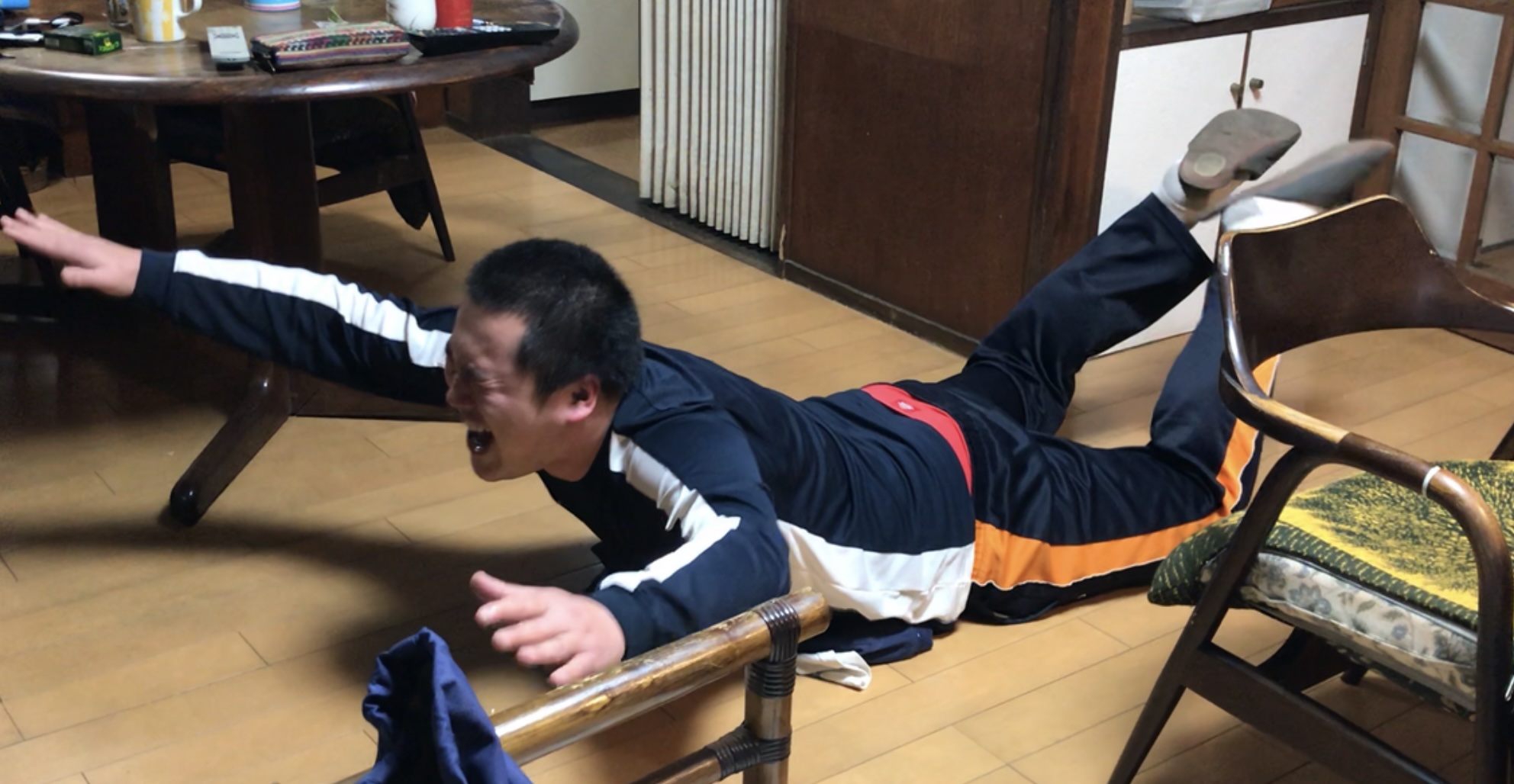

Tokyo Uber Blues is best when it works as a borderline psychodramatic character study, documenting the filmmaker’s descent into madness as his little earnings dwindle fast. Some moments, such as when Aoyagi attempts to hire a sex worker at a discount COVID rate, feel as inherently pathetic as a Conner O’Malley character, and it does feel like the filmmaker deliberately hams it up for the cameras, not to mention consciously pushing himself further into poverty so he can partake in some gonzo journalism. The use of broad, lowbrow humor to highlight the ways in which so many gig economy workers are one late payment away from homelessness is necessary to introduce these circumstances to wider audiences, who may have not thought twice about their living conditions. But it appears contrived when contrasted with the sobering facts of a typical day-to-day shift, when even a 10-hour stint can end with only $50 to take home, forcing couriers to burn themselves out to get anything approaching a living wage. Aoyagi didn’t need to resort to extremes for this to make an impact.

Tokyo Uber Blues Review: Related — Know the Cast & Characters: ‘Sick’

Aoyagi’s self-imposed predicament reminds me of another recent Japan-set documentary, The Contestant (2023) — an account of unsuspecting 90s reality TV star Tomoaki Hamatsu. For a year, he was filmed naked in his apartment, and told he couldn’t leave until he’d won a million yen’s worth of magazine prizes, which he’d have to live off. Hamatsu wasn’t permitted to wear clothes until he’d won some, for example. He didn’t know his exploits were being broadcast to tens of millions of viewers, which made his descent into mania feel genuinely harrowing. The director/star of Tokyo Uber Blues may have only been a small child when that series (Susunu! Denpa Shōnen) was making headlines, but its enduring impact on Japanese culture — the show is now the country’s go-to shorthand for reality TV that sadistically takes advantage of its contestants — has created a template that Aoyagi’s documentary feels like its striving to emulate.

Tokyo Uber Blues Review: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘The Bubble’

This isn’t to say that all of Aoyagi’s experiences feel contrived, nor do I want to minimize the dehumanizing impact of working in such an isolated role. But many of the filmmaker’s decisions throughout Tokyo Uber Blues feel more like those of a canny film producer, self-aware as to how to push a grounded tale of worker exploitation to its furthest extremes, rather than a budding Uber Eats employee determined to make a living. Aoyagi initially stays with friends, but the director is clear that he doesn’t want to be a burden, and so he leaves after a few days without being kicked out first. It’s one of several moments where I felt myself having to suspend disbelief, as while the speed with which the subject becomes homeless is true to many people’s experiences in this line of work, it feels deliberately engineered.

Tokyo Uber Blues Review: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Stuck Together’

Of course, Tokyo Uber Blues is hardly the first documentary in which the subject would be alleged to have manipulated his circumstances for the benefit of on-screen drama, and it’s easy to conclude that the film wouldn’t have attracted international attention if it remained focused on the impossibilities of making this job into a financial safety net. Removing any form of a safety net in Tokyo Uber Blues highlights the desperation that’s all too common for many people, but Aoyagi’s documentary would have had more of an impact if what laid beneath remained a harsh threat, rather than a narrative guarantee.

Tokyo Uber Blues premiered as part of PBS’ POV documentary series on October 21, 2024.

Alistair Ryder (@YesitsAlistair) is a film and TV critic based in Manchester, England. By day, he interviews the great and the good of the film world for Zavvi, and by night, he criticizes their work as a regular reviewer at outlets including The Film Stage and Looper.

Tokyo Uber Blues Review: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Stuck Together’

Categories: 2020s, 2024 Film Reviews, Documentary, Featured, Film, Movies

You must be logged in to post a comment.