Crime Scene is a monthly Vague Visages column about the relationship between crime cinema and movie locations. VV’s Five Deadly Venoms essay contains spoilers. Cheh Chang’s 1978 film features Sheng Chiang, Chien Sun and Phillip Chung-Fung Kwok. Check out film essays, along with cast/character summaries, streaming guides and complete soundtrack song listings, at the home page.

*

Most of the featured movies in this column are unequivocally “crime” films. Just as importantly, all of the movies covered thus far were unabashedly marketed as crime productions — no questions about genre whenever it comes to their trailers, poster artwork or expected audience. This time around, I’m going in a different direction with a legendary Shaw Brothers kung fu film that slips in a criminal conspiracy whodunit underneath the expected fisticuffs: Five Deadly Venoms, directed by Chang Cheh (1978, alternatively called The Five Venoms).

The Shaw Brothers studios, in their heyday, churned out films by the bucketload. For most Western viewers, their logo is inextricably linked to martial arts, with the company’s biggest worldwide hits in the 70s and 80s being kung fu flicks. Many of the plots are broadly interchangeable, revolving around stories of young heroes overcoming adversity against ne’er-do-wells, usually with the help of an aging master. That sense of interchangeability is only made more concrete by the extensive use of the Shaw backlots in Hong Kong’s Clear Water Bay Film Studio: watch enough of these movies and you’ll notice sets and props being continually reused, a result of the company’s famously parsimonious filmmaking techniques.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast & Characters: ‘Emily the Criminal’

But amidst that interchangeability, the studio continually produced films of genuine artistry, genius and pure entertainment, courtesy of a talent pool which was able to rely on a continuous stream of work in which to hone their craft. By the late 1970s, Shaw Brothers had been the dominant studio in Hong Kong for at least a decade, though Golden Harvest (who had signed Bruce Lee) was starting to catch up. Chang was the star director, having gradually shifted from wuxia films (The One-Armed Swordsman, 1967) to the hand-on-hand bloodiness of kung fu from the early-to-mid-70s onwards, in accordance with prevailing audience tastes. The filmmaker was unrelentingly busy, directing as many as five or six productions a year (he clocked up almost 100 features during his career). By the late 70s, however, Chang’s star was being eclipsed by his former pupil Lau Kar-leung, who had begun his career as an action choreographer before breaking out into directing on his own.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Sniper: G.R.I.T.’

These two careers form a fascinating instructive on the possibilities of the action film form. Lau, a bona fide martial artist, utilized his movies to showcase kung fu styles and philosophies, sometimes completely at the expense of plot; his 1978 film Heroes of the East essentially ditches the story in the second half to become one long fight scene. Chang’s films tended to be more narrative and plot-focused, animated by his favorite themes of brotherly love, male bonding and camaraderie. Many critics read a certain homoeroticism to his movies, aided by his love of having characters dispatched through impalement, as Chinatown Kid (1977) literally has one fight end after a baddie gets stabbed in the ass, though Chang himself strongly rejected any such suggestions.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Dune: Part Two’

Whether it was out of a desire to remain in a privileged position at Shaw with newcomers snapping at his heels or a genuine desire to experiment with his craft, Chang frequently found ways to freshen his methods when budgets allowed. Though much of the filmmaker’s output focuses largely on wuxia and kung fu movies, he did utilize crime film elements in his work: The Boxer from Shantung (1972, with Hsueh-Li Pao listed as co-director) and Chinatown Kid are both structured as rise-and-fall gangland narratives. But the construction of the thriller elements in Five Deadly Venoms are the most interesting and well-developed; a complex mystery about criminal conspiracy and corruption under the guise of a kung fu flick. Chang deploys the standard tropes and iconography of the Shaw Brothers style with the pieces re-arranged. Suddenly, a layout that one has seen a hundred times before re-emerges fresh.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Fresh’

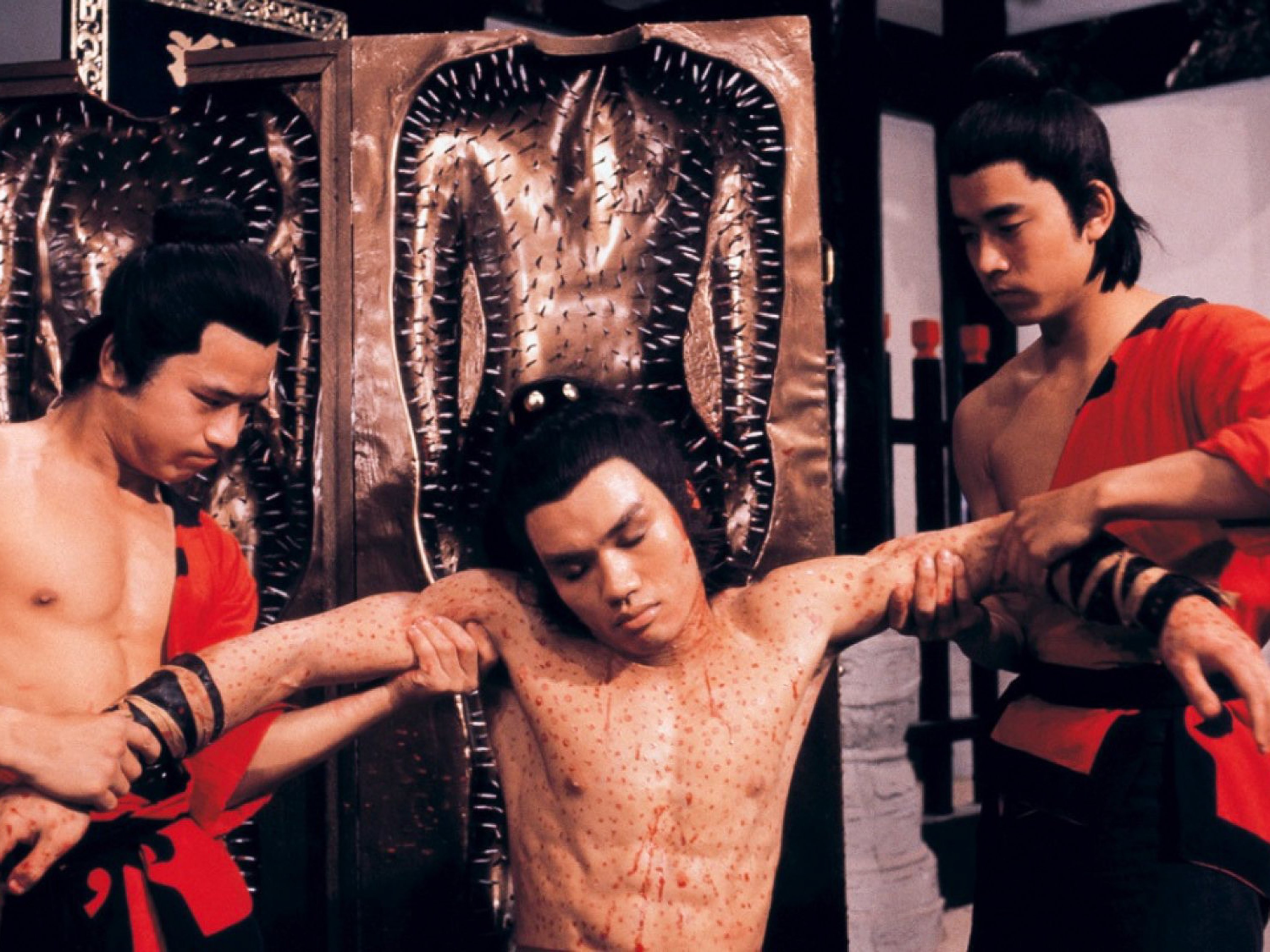

The opening scenes of Five Deadly Venoms introduce the main fighters, each with unique styles related to a poisonous animal: Centipede (Lu Feng), Snake (Wai Pak), Scorpion (Sun Chien), Gecko (Philip Kwok) and Toad (Lo Mang). The dying master of the Venoms style tells the disciple Yang Tieh (Chiang Sheng) to seek out the rest of clan and restore their reputation, with various members trying to track down an ill-gotten treasure. The rub, however, is that the characters are mostly only familiar with each other through their fighting styles. Thus, when Yang arrives in the city, he has little to go on.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘The Privilege’

It gradually emerges that some of the Venoms have found each other, but the group has largely split into two camps (one good and one bad) that broadly work in the dark, unaware of who or what they’re up against — a fact that’s further complicated when bodies start dropping as the evil Venoms try to cover their tracks.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Television: ‘Bodies’

The more complex, plot-driven nature of Five Deadly Venoms also means that it’s a more “talky” film than its contemporaries, as the protagonists continually have to work with new information. Thankfully, the meat of the movie is in Chang’s classical, highly detailed filmmaking, elevating the whodunit qualities into more than a plot strand while dipping into political corruption, betrayal and power.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘The Burial’

A big part of Five Deadly Venoms’ magic is how Chang utilizes familiar Shaw sets. As with so many of the studio’s films, the movie is set in some unnamed part of Chinese history in an unnamed Chinese town. The presence of an Imperial Court and pre-modern architecture suggests Qing Dynasty, but this could be anywhere, especially for non-Chinese-speaking viewers largely unfamiliar with the details. The artificiality of the town compounds matters, as the Shaw Brothers’ have a habit of making their films feel fable-like and semi-mythic (which is part of the appeal).

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Television: ‘Servant’

The lack of physical locations places limitations on scale, as the focal setting could be a village of a hundred or a city of a million. Chang maneuvers around this in wide shots by giving the sets a sense of packed-in claustrophobia. Street fights happen in narrow alleyways, limited by the walls either side, while characters frequently bump into each other on street corners or see things they’re not supposed to by hiding behind walls and bushes. Even the temple which serves as the birthplace of the Venoms style is a dingy, dungeon-like space in which no sunlight arrives. Perhaps the only “open” space in Five Deadly Venoms seems to be the Imperial Court, with studio-powered sunlight filtering in through the wide garden and open courtroom.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Anatomy of a Fall’

Open space lighting plays nicely into Five Deadly Venoms’ plot, where the fortunes of the subjects are directly tied into whoever has the ear of the local authorities, with the courtroom being the location where power structures are most visibly played out. As Chang slowly reveals the identity of each Venom, it becomes clear that they’ve gradually integrated themselves into the town’s daily life: one is a detective in the police force, and another is a local businessman. Their secret assimilation into local life powers the intrigue at the heart of Five Deadly Venoms’ plot, as the bad-guy characters utilize their influence to shift suspicion away from themselves, going as far as to bribe jail guards into poisoning their inmates and then killing any witnesses. On Simon Abrams’ audio commentary for the Arrow Video release, he remarks on how Chang delineates between private and public spaces in the film. Offices, living rooms or semi-private spaces like jail cells are used for plotting and scheming, while public spaces like the city streets, the eatery or the courtroom are where realism emerges through legal decree or hand-to-hand combat.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Brawl in Cell Block 99’

The spatial detail in Five Deadly Venoms, aided by Chang’s sharp sense of timing, helped the film become a surprisingly labyrinthine vision of camaraderie in the face of corruption and power. The lack of “real” locations may be a natural side-effect of the Shaw style, erasing local specificities in favor of a more general “Chinese-ness” that could be sold across the diaspora, but equally it allowed the better directors in the studio stable greater control over the camera, ensuring that their consummate professional craftsmanship superseded the generic material. And so Five Deadly Venoms reached classic status by stretching the Shaw style to new places, courtesy of fresh ideas and the central twist-driven criminal conspiracy.

Fedor Tot (@redrightman) is a Yugoslav-born, Wales-raised freelance film critic and editor, specializing in the cinema of the ex-Yugoslav region. Beyond that, he also has an interest in film history, particularly in the way film as a business affects and decides the function of film as an art.

Five Deadly Venoms Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Se7en’

Categories: 1970s, 2024 Film Essays, Action, Crime Scene by Fedor Tot, Drama, Featured, Film, Movies, Mystery

You must be logged in to post a comment.