I’ve seen the best movie minds of my generation destroyed by selective nostalgia, asserting that Leonard Wilhelm DiCaprio, who established a cinematic legacy by age 22, didn’t have proper movie star credentials when Titanic plunged him into the psyche of mainstream moviegoers. In Slate’s February 2020 article “Was Leonardo DiCaprio Actually a Star Before Titanic?,” a group of well-meaning journalists debate the merits of young Leo’s early-career accomplishments, but somehow fail to even mention The Basketball Diaries, the 1995 drama that solidified DiCaprio’s star status before he portrayed the great poet Arthur Rimbaud, before he squeezed into Romeo Montague’s filthy threads, before he co-starred with Robert De Niro (for the second time), before he painted classy nudes and slept with the fishes in Titanic.

The collective code complex of Slate’s journalists can be easily explained by what I call the Reverse Robert Pattinson Effect, or the loss of memory when thinking about an actor’s filmography before a career-defining performance. For example, there’s a certain group of movie buffs who will forever view Robert Pattinson as Edward Cullen from the Twilight franchise, and remain ignorant to his eclectic filmography from 2012 onward, beginning with David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis. The same concept applies with DiCaprio, only memory-challenged movie rubes often forget about, or misrepresent, every performance prior to Titanic.

Slate’s Dan Kois notes that “the vast majority of adult moviegoers did not know Leonardo DiCaprio before Titanic came out,” implying that the average movie nerd was simply incapable of expertly navigating the local video store’s Drama section. Such DiCaprio ignorance shows that selective pop culture nostalgia overrides the facts. For one, DiCaprio earned and cultivated a vast fanbase during the early 90s by landing main roles across various genres: a horror film, an erotic thriller, a coming-of-age drama, a western, a biopic and a Shakespeare adaption. And don’t forget about the impact of Growing Pains or DiCaprio’s big-boy performance in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape; a film that that preceded his first leading role as a proper movie star in The Basketball Diaries .

More by Q.V. Hough: Martin Scorsese, ‘Mean Streets’ and Caravaggio’s Moment of Illumination

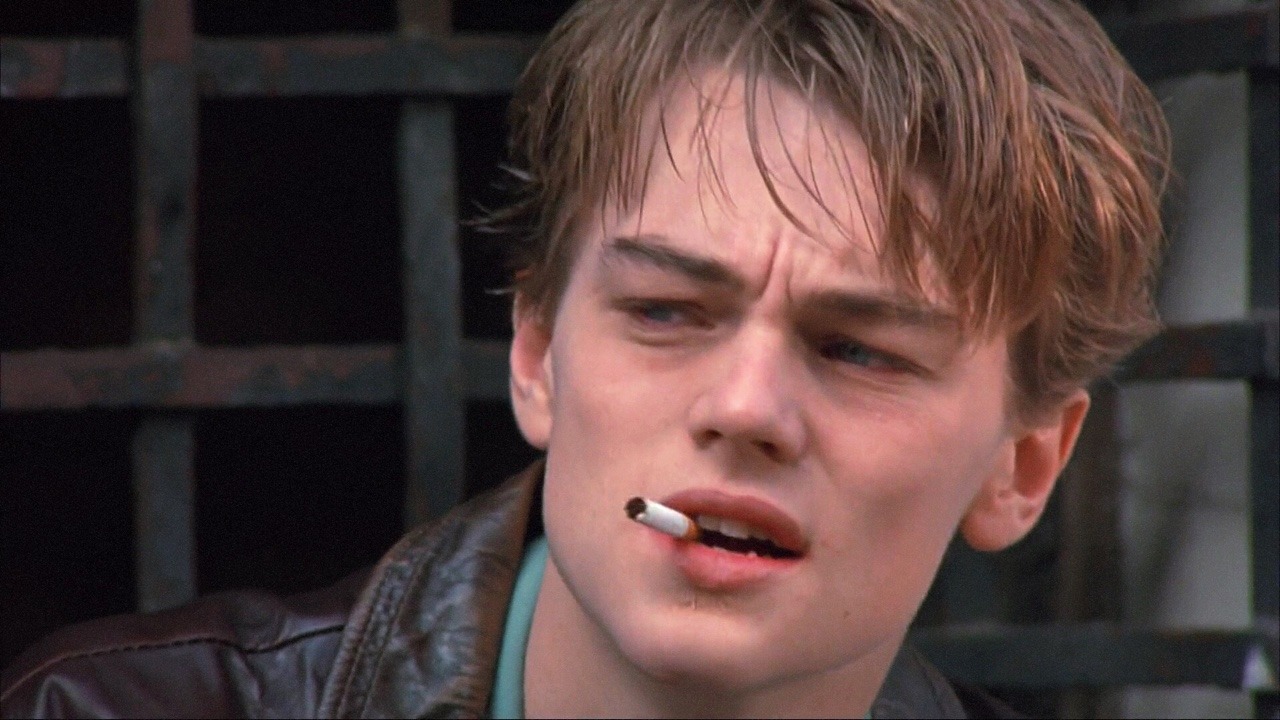

The Basketball Diaries, an adaptation of Jim Carroll’s eponymous 1978 autobiography, betrays common perceptions about “pretty boy” DiCaprio, and pre-dates his gritty performance in Martin Scorsese’s The Departed by over a decade. DiCaprio stars as Carroll, a real-life author and Manhattan native who overcame a heroin addiction in the late 60s, and later became associated with New York City’s punk scene. Authenticity and emotional depth is key for DiCaprio’s performance in Scott Kalvert’s feature adaptation.

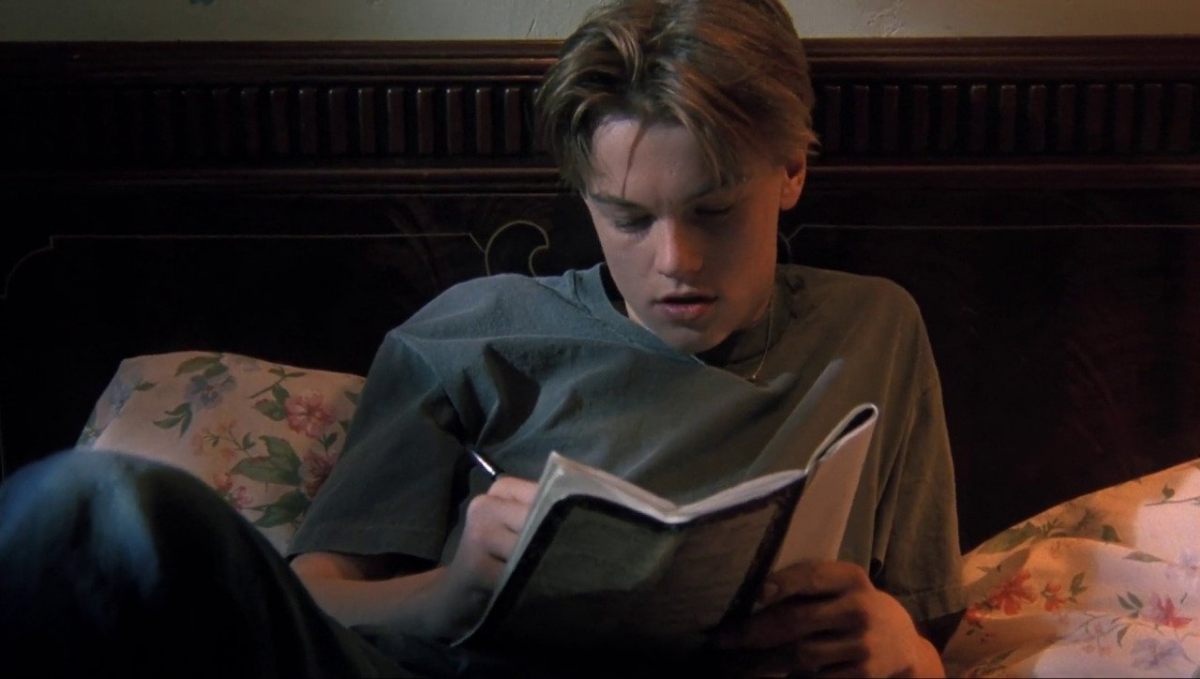

Crucially, The Basketball Diaries doesn’t begin with glamour shots of DiCaprio brooding, or even pretentious images that over-romanticize the craft of writing. Instead, DiCaprio sets the mood through hard-boiled voiceover narration, a recurring motif throughout. Soon after, his character screams at an elderly female neighbor, and then receives a classroom beating, courtesy of his Big Apple teacher. In these moments, DiCaprio exudes the star appeal that would fuel Titanic, but also shows that he might’ve been the perfect candidate for a 90s adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye, at least if J.D. Salinger would’ve ever allowed anybody to portray Holden Caulfield on screen.

DiCaprio has shown a career-long tendency to overact, using vocal bravado and stiff body movements to emphasize dialogue. In almost every DiCaprio film, there’s a moment where his character laughs maniacally, delivers a sharp head turn, points at someone and then proceeds with a proper rant. That can be fun for viewers, but it’s not always effective in scenes with other performers. In Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, DiCaprio shows that he’s learned how to harness that mad-as-hell energy, evidenced by shared scenes with performers young and old. There are several questionable ACTING! moments in The Basketball Diaries (exaggerated crying, mouthed words while writing), but they are crucial for character psychology as Carroll evolves from a hardened street-smart kid into a self-aware adult.

More by Q.V. Hough: Novella Review: Jared Feldschreiber’s ‘Reckless Abandon’

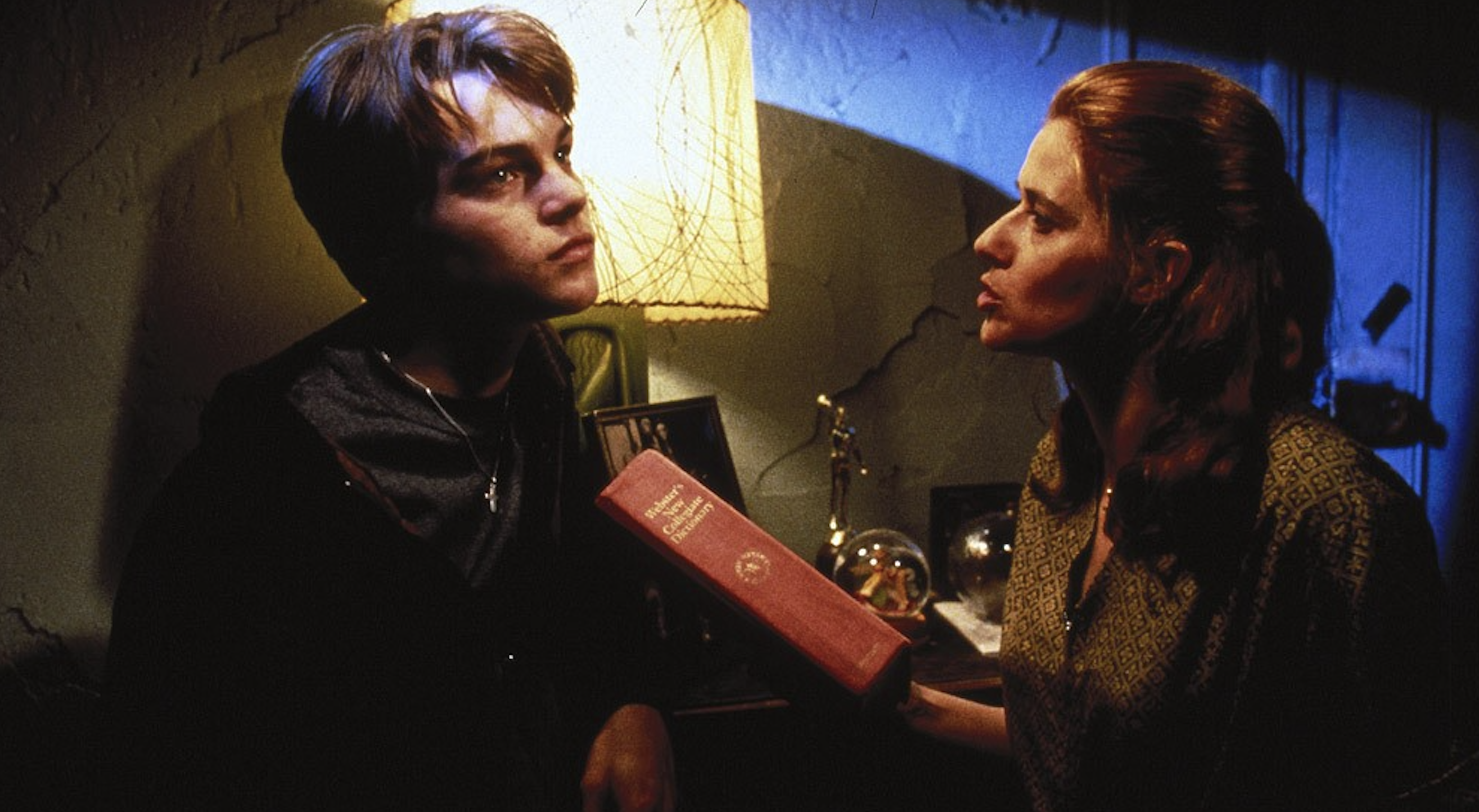

DiCaprio’s physical stature noticeably affects the power dynamics in The Basketball Diaries . In several group walking shots, he’s clearly one of the two tallest actors, which subconsciously plants the idea that Carroll is the leader of the pack; the quintessential handsome high school star athlete; the guy that appeals to people of all ages. And that premise sets up The Basketball Diaries’ low-key inciting incident, as Carroll’s coach, Swifty (Bruno Kirby), makes a sexual proposition in a school bathroom. Here, performative nuance becomes critical for DiCaprio, especially for an early 90s film that appeals to one crowd with its title and another by addressing heavy topics like drug addiction and sexual predators.

Even if height doesn’t seem that relevant to the average viewer, the collective performances do indeed establish DiCaprio as the undeniable star. Essentially, there are three breakout performances in The Basketball Diaries: there’s DiCaprio (the clear frontrunner), there’s Mark Wahlberg (the Alpha Male), and there’s Michael Imperioli — who would later star as Christopher Moltisanti in The Sopranos. Despite Wahlberg’s obvious charisma, his worst scenes as Mickey are bad enough to pull the viewer away from the film. And Imperioli simply doesn’t receive enough screen time as Bobby to rival DiCaprio, who spends the majority of the The Basketball Diaries reacting to others, or reacting to his addiction. Meaning, DiCaprio is less Nic Cage and more James Dean.

More by Q.V. Hough: On Performance by Q.V. Hough: Rosamund Pike in ‘A Private War’

When the real Carroll first learned that DiCaprio had been cast for The Basketball Diaries, he made a telling statement about his perception of the young actor whose name he didn’t recognize: “If they’d said the kid from Growing Pains, I would have known, because when I first saw that kid, I said, ‘This kid has a lot of presence.’ I said, ‘That kid is very pretty. He’s gonna do well.’” Notice how Carroll doesn’t cite an early ‘90s DiCaprio film, but rather a early ‘90s television role.

With DiCaprio, people often look back through a nostalgic lens in the same way they do with Dean — they see Titanic and Rebel Without a Cause; the ‘90s pretty boy and the iconic Hollywood outsider. The reality, however, is that both actors established themselves on network television first, and then landed high-profile movie gigs with acclaimed feature filmmakers. In 2021, Dean may be remembered most for his third and final film Rebel Without a Cause, primarily because of its cultural legacy, but it’s lazy for anyone to automatically dismiss his performances in Elia Kazan’s East of Eden and George Stevens’ Giant because they’re not necessarily synonymous with 50s pop culture. When looking at The Basketball Diaries, DiCaprio works from Dean’s playbook for structure and applies it to the 90s for dramatic purposes: the style, the slight overreacting with paternal figures, the side-eye rebellion.

In The Basketball Diaries, DiCaprio channels Dean’s cultural image with a signature green jacket and black beanie, a modern update of the red jacket and white tee from Rebel Without a Cause. For storytelling, Carroll’s Underground Man style reminds the audience that he has fully transformed into a new persona, even though the chip on the shoulder remains. Incidentally, the audience bears witness to a so-called pretty boy devolving into a no-fucks-given drug addict. To reference a later DiCaprio film, Inception, an idea has been planted: the code complex has been cemented in the audience’s subconscious, all the while keeping them intrigued about the lead actor’s potential. To use a cultural sports correlation for The Basketball Diaries, think of NFL quarterback Tom Brady. He was a star quarterback at the University of Michigan in the late 90s, and then became a superstar with the New England Patriots. Should his collegiate accomplishments be ignored because he won six Super Bowls and married Gisele Bündchen? No, of course not.

More by Q.V. Hough: The Code Complex: Robert De Niro, Jake LaMotta and ‘Raging Bull’

Much of The Basketball Diaries involves DiCaprio gliding like a long-distance runner. He’s fluid on the court, and moves confidently in the street. And DiCaprio’s voiceover narration solidifies Carroll as a smooth operator; an observant and intellectual outlier who’s skeptical of authority. During scenes with coach Swift, DiCaprio communicates a sense of genuine unease without speaking a word, much in the way that Dean expresses resentment as Jett Rink when dealing with the rich folk of Giant. And when Carroll hits rock bottom, pounding on his mother’s door and crying in her arms, DiCaprio hams it up like Dean in Rebel Without a Cause’s opening jail sequence, along with the famously-improvised money scene in East of Eden. All of these star moments involve the young protagonists looking for acceptance from their parents. Curiously, DiCaprio’s early 90s accomplishments have been widely dismissed or ignored ever since Titanic’s Jack Dawson become a beloved movie figure amongst parents and their nostalgia-loving kids.

In 1995, DiCaprio had already established a performative code; a way of maximizing the efficiency of craft techniques. Little did he know that standing on the bow of the RMS Titanic would create a pop culture complex amongst American moviegoers. The 90s may be dead and gone, but The Basketball Diaries exists.

This essay was originally published by the now-defunct REBELLER.

Q.V. Hough (@QVHough) is Vague Visages’ founding editor and a Screen Rant staff writer.

Categories: 1990s, 2021 Film Essays, Biography, Crime, Drama, Featured, Film Essays

4 replies »