Vague Visages’ The Fishing Place review contains minor spoilers. Rob Tregenza’s 2024 movie features Ellen Dorrit Petersen, Andreas Lust and Frode Winther. Check out the VV home page for more film criticism, movie reviews and film essays.

Is it disrespectful to Holocaust victims to keep mining their trauma for the sake of making an emotional impact in cinema? And can any contemporary movie set during World War II have a deep resonance now that we’re so far removed from it, or do filmmakers simply rely on familiar symbols and easy distinctions between good and evil in the hope of resonating with as wide an audience as possible? In its final act, The Fishing Place tears down the fourth wall to interrogate the film’s creative process, finding a crew entirely detached from the historical setting and its wider reaching implications, their entire focus being on staging the production’s elaborate shots.

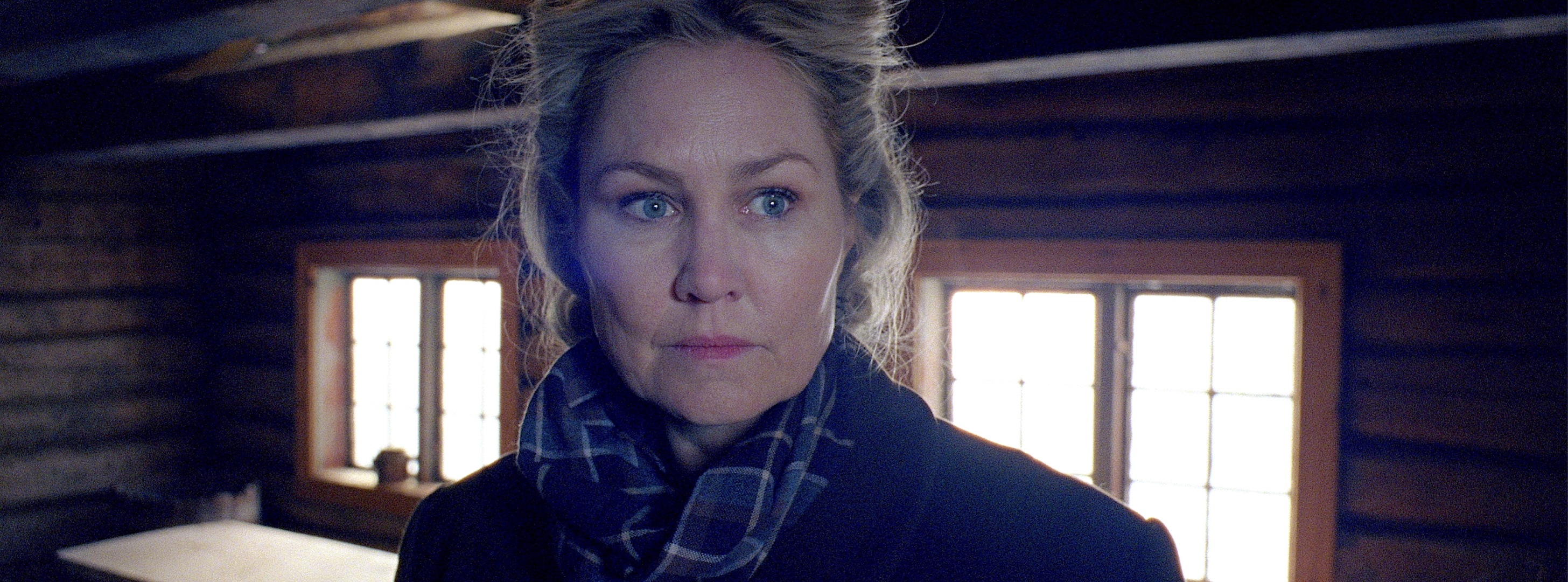

It’s a thorn in the side of the narrative which came before it, but one that makes director Rob Tregenza’s latest film far more engaging than when taken as a period piece at surface level. The director, a 74-year-old filmmaker whose best known work is arguably as a cinematographer (he shot Bela Tarr’s apocalyptic 2000 masterwork Werckmeister Harmonies), was similarly born in the immediate aftermath of the war, and — throughout his life — has undoubtedly seen WWII stories grow increasingly impersonal. Now, this era is more commonly invoked not through an autobiographical lens, but a heightened one closer to genre cinema, if only to lazily utilize the inherent stakes that come with existing during this period. That’s certainly the case for Anna (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), who has been released from her imprisonment by the Nazis to find out if a priest (Andreas Lust) in a Norwegian fishing village is working with the resistance movement.

The Fishing Place Review: Related — Review: Michel Hazanavicius’ ‘The Most Precious of Cargoes’

The protagonists’ dual crises of faith are largely interior, with the director relying on the suffocating beauty of the snowy, rural setting to hammer home the juxtaposition of being prisoners of fascism, both literally and metaphorically, in a village which still feels like an untouched winter paradise. Whenever The Fishing Place focuses on the torment of those embedded within the hierrarchy of the Third Reich, it feels comparatively shallow, such as a heightened sequence — bordering on interpretive dance — in which a Nazi officer contemplates suicide. The moment almost feels like a parody of The Zone Of Interest’s (2023) closing sequence, which itself is a nod to the finale of Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 documentary The Act Of Killing — a horrific gaze into the genuine mindset of a perpetrator of genocide, which gets watered down further with each new adaptation.

The Fishing Place Review: Related — Review: Alex Garland’s ‘Civil War’

It’s this increasing detachment from tragedies that The Fishing Place’s closing chapter wants the audience to ruminate on, but I can’t help but feel there would be a stronger, more incisive way to interrogate this rather than make viewers sit through a slow cinema interpretation of the genre at its laziest. It’s handsomely mounted but offers little beyond regurgitated cliches when taken at face value. And that might be the point, but the third act isn’t enough of a rug pull reveal to make it all feel worth it. While Tarr might be the previous Tregenza collaborator to be most extensively cited in reviews, purely because of their shared aesthetic interests, the film’s function as an angry work of art criticism is far more evocative of the legendary Jean-Luc Godard — the uncredited producer of the director’s 1997 film Inside/Out — or the British firebrand Alex Cox, whose 1998 film Three Businessmen was shot by Tregenza.

The Fishing Place Review: Related — Building the New Queer Canon #1: Isao Fujisawa’s ‘Bye Bye Love (Baibai Rabu)’

Both Tregenza and Cox have made polarizing works articulating the whitewashing of history within Hollywood narratives; the latter filmmaker even received a lifelong pass to Director Jail thanks to a film (1987’s Walker) that highlights how the biopic genre can cement monsters as heroes through their very structure. The commentary within The Fishing Place is nowhere near as explicit, with all communication between the workers being dry and analytical overviews of the requirements of any given scene. Perhaps the fact that there’s no clear discussion of any larger artistic intent is the most cynical thing; the tragedies of an earlier generation are now routinely relived as mundane filmmaking exercises.

The Fishing Place Review: Related — Review: Rich Peppiatt’s ‘Kneecap’

Director Michael Haneke famously dubbed the idea of making a Holocaust film “unspeakable,” criticizing Schindler’s List (1993) in the process. Tregenza’s 2024 film is most interesting when viewed as a movie on that wavelength, critiquing the extents filmmakers will go in order to re-stage tragedies in a way that looks good onscreen. However, it’s a shame that the conversations The Fishing Place will provoke just might be far more substantial than anything within the film itself.

Alistair Ryder (@YesitsAlistair) is a film and TV critic based in Manchester, England. By day, he interviews the great and the good of the film world for Zavvi, and by night, he criticizes their work as a regular reviewer at outlets including The Film Stage and Looper. Thank you for reading film criticism, movie reviews and film reviews at Vague Visages.

The Fishing Place Review: Related — Vague Visages Is FilmStruck: Michael Haneke’s ‘Benny’s Video’

You must be logged in to post a comment.