This assassin essay contains spoilers for Point of No Return, The Long Kiss Goodnight, Grosse Pointe Blank, Assassins, The Jackal and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Check out Vague Visages’ film essays section for more movie coverage.

As the Cold War came to an end, the initial glow of victory dissipated to a grumbling unease; the triumphalism of the moment was followed by a dangerous lassitude. Beneath the apparent stability and affluence of the 1990s was an underlying ennui and anxiety, a sense of existing in a fragile ceasefire with history. What had previously clarified so much of life evaporated, leaving many searching for a new purpose — a new antagonist against which one could be defined. For all the talk of the end of history and a new world order, there was a shared recognition that this moment constituted a tense interregnum, a lull between historical currents, before the fractured pieces of history would reassemble into whichever tortured form it took. The weapons that had repelled external enemies would punctuate a cultural conflagration that was symbolized in the figure of the school shooter, the domestic terrorist, the cult leader, the disgruntled employee. The traditional hitman is an intrinsically historical actor; they embody the certainty of a fixed target, to whose elimination all else is subordinate. They have no truck with any complicating introspection or ideological contention; they simply have a job to do, one which encompasses the mute teleology of a mission that is necessarily obscure to them. The 90s variant of the hitman archetype became entangled in the disorientation of the time, prone to the same neurotic preoccupations as the cultural cadres warring around them; the violence they dealt in was aestheticized into rolling news and balletic revenge fantasies. A single shot could no longer compete with this immense spectacle, and the modern assassin bowed to the pressure.

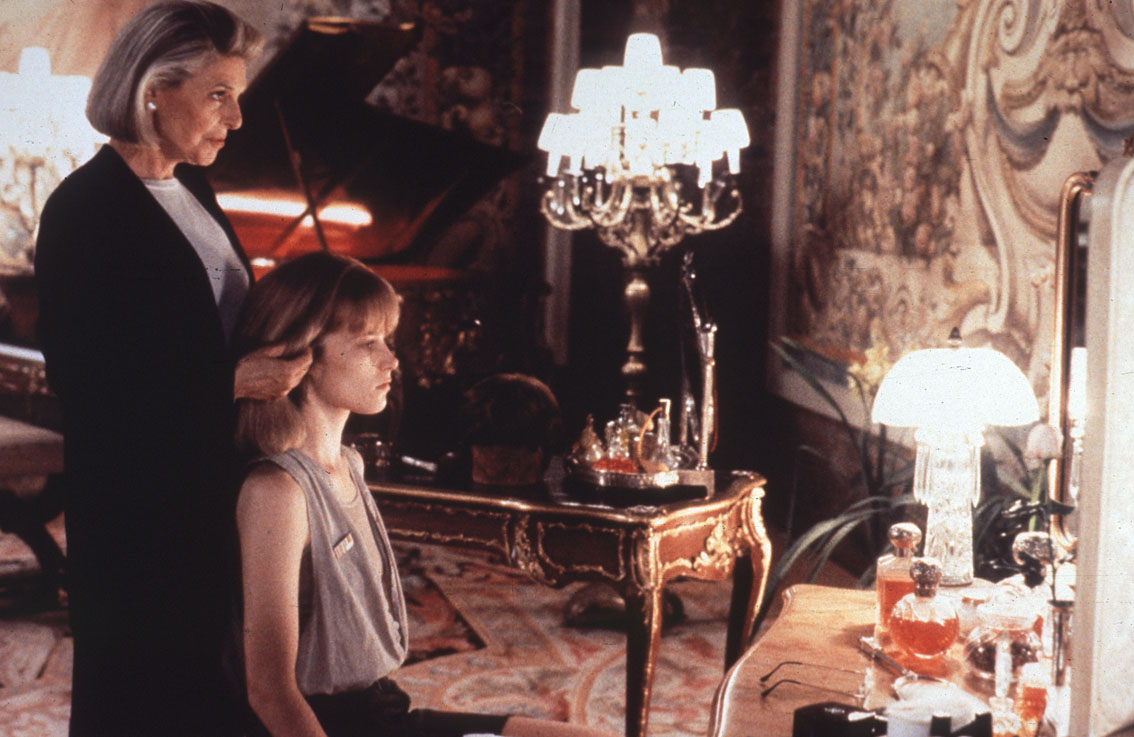

In Point of No Return (1993) — John Badham’s remake of Luc Besson’s La Femme Nikita (1990) — Maggie (Bridget Fonda) is salvaged from a morass of self-destruction and thrust into the seductive world of orchestrated state violence. Maggie is a heroin addict in Washington, D.C., who murders a cop during a botched pharmacy robbery. Sentenced to be executed, Fonda’s character is recruited by Bob (Gabriel Byrne) to join his crack team of government assassins. A 90s take on Pygmalion follows, with the grungy slacker being turned into a refined killing machine. Maggie begins as the definitive Generation X subject, self-absorbed and cynical, but she is urged by Bob to harness her inner rage and to “do something for your country for a change,” to serve the newly regnant empire by heading off any potential threats, to reject her solipsism and live up to the new demands of the moment. Maggie and her cohorts offer their employer new methods of control and power projection, drawn from the surplus population as sirens of the democratic spirit that had assumed primacy, dashing putative enemies on the rocks of political reality. The totems of the freshly hegemonic culture are leveraged to sell an idea of authenticity to the world, offering the possibility of being co-opted while bringing your cultural signifiers with you. Maggie is codenamed “Nina” after her fondness for Nina Simone, which she blasts from her increasingly squalid holding cell, signaling defiance while being captured.

Assassin Essay: Related — The Loneliness of the Contract Killer: Music in ‘Murder by Contract’

Maggie is stripped of her previous garb and steps into another deadly pretense; her relationship with Bob is consummated in a massacre at an upscale D.C. restaurant which proves to be her final test. The violence is pulled off with all the poise of a Gene Kelly musical number and the precision of industrial machinery, an indication of how style and violence reached new heights (or depths) in the 90s. In the fantasy of the hitman (or woman), killing is an act of seduction, a tactical weakening of resolve, a moment of sensuous excess that obliterates all rational thought. But what is interesting is that sexuality is not Maggie’s weapon; gender is used as a kind of red herring in Point of No Return; Maggie kills her targets the old way — she must compete on an equal footing. The anithero is sent out into the world and finds herself a boyfriend, J.P. (Dermot Mulroney), a good-natured photographer who quickly gets frustrated by Maggie’s evasiveness when it comes to her past, telling her “You’re like living with a ghost.” But Fonda’s character honors a higher narrative; she passes herself off as a plausible civilian while never losing sight of the fact that her peace is temporary and tenuous. Maggie knows the call will come one day, that her generation will have to take up arms in the continuous struggle against whichever adversary emerges. She has been inculcated with the prevailing paranoia of the agency, combatants in a battle taking place beneath the surface of everyday life. The “bad guys” have become even more terrifying for no longer having a discernable form; there are now many potential candidates to occupy the role of chief antagonist to the undisputed hegemon. Maggie manages to extricate herself from this wilderness of mirrors, but it comes at the expense of everything; she walks through the morning mist knowing she is free from history’s injunctions.

Assassin Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘The Day of the Jackal’

Another dislocation takes place in The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996), but smalltown schoolteacher Samantha Caine (Geena Davis) is expelled from a life of domestic stability and tranquility when a car accident triggers dormant parts of her personality. Renny Harlin’s high-octane dash taps into an anxiety surrounding the apparent comfort of the new peacetime footing — that the empire’s latent killer instinct can quickly be activated, that the country is a slumbering beast lulled into submission, but it would only take one shock to rouse it. Samantha leaves her new family behind and sets off with sleazy private detective Mitch Henessey (Samuel L. Jackson) on a journey to discover who she really is. On the other side of her amnesia, she learns that she was “an assassin working for the United States government,” believed to have been eliminated in a botched “clean-up mission.” The intelligence operatives tasked with cleaning up their mess and tracking down Samantha (or Charly as she was previously known) speak of her as “a relic of the Cold War,” an unsightly outgrowth of old imperatives which the permanent government must expunge in the interest of preserving the new spirit of accord. But these forces are restless, and Samantha uncovers a plot which strikes a chilling note in its details — elements within the intelligence community are planning a false flag attack involving a “chemical bomb.” They will “blame it on the Muslims” and kickstart history, inflating defense budgets to the peaks they had enjoyed at the height of the Cold War. Like the plotters, Samantha is wrapped up in the entanglements of her past; history nips at her heels as she tries to run — her old self stalks her nightmares and announces, “I’m coming back.”

Assassin Essay: Related — We Are Our Media: ‘Assassination Nation’ and Pop Art Society

In its own overblown way, Shane Black’s screenplay asks where the violence goes without an outlet, contending that it can only be sublimated for so long in the development of the self and the pleasures of consumption. Samantha is engaged in a conflict between the mother she is and the killer she was, and Charly threatens to wipe out everything she has built since she woke up on a beach with “lots of scars,” pregnant and with no recollection of how she got there. She is a testament to the endless mutability of American identity, how the will can define life beyond the bounds of memory. Samantha’s pursuers are haunted by an institutional death drive; they cannot abide the torpor of their historical settlement — they long for the blood and glory of the old fight, they seek to revive the feeling of life lived on a knife’s edge. To achieve this, they must upturn the world order again with their “Operation Honeymoon,” a catalyzing incident designed to stir up strategically useful fear and animus. Charly must use the skills she was taught by her government to revive Samantha and save her child; she must occupy the dark side of the street to return to her sleepy rural idyll, to keep history in abeyance. In doing so, she comes to embody the logic of the cold warriors who argued that security comes at the cost of constant vigilance. But for all its liberal hawkishness, The Long Kiss Goodnight is shot through the distrust of government which grew throughout the 90s; it is loaded with conspiracy tropes which speak to a growing frustration at a political pact in which both major parties exist within a narrow ideological field. Samantha’s experience is salutary in outlining that nobody is innocent, nothing is at it seems and nothing is ever simple. These are lessons which those in power chose to ignore when retaliatory terror reared its head and set the 21st century in motion.

Assassin Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Television: ‘The Day of the Jackal’

In Grosse Pointe Blank (1997), contract killer Martin Blank (John Cusack) is in a rut. His job no longer inspires him, as it has come to feel like a tedious retail position, stripped of the geopolitical resonance it once held, simply serving up bodies for private clients. To make matters worse, the market has been flooded with new talent from the dissolved Soviet bloc, leading fellow hitman Grocer (Dan Aykroyd) to propose the formation of a quasi-union, a proposal lone wolf Martin is loath to countenance, branding it a “dirty little guild.” Martin needs something to break him out of the cycle of repetitive hits. He’s also starting to lose focus; he botches a job and must travel to his old Michigan stomping ground to make amends to his aggrieved client with a gratis hit. Martin’s dutiful secretary, Marcella (Joan Cusack), has been reminding him that his 10-year school reunion is coming up, and she urges him to go, amused by the notion that he has a normal human origin. Cusack’s hit man sees the possibility of reconnecting with Debi Newberry (Minnie Driver), his high school sweetheart who he stood up at the prom when he fled town. But Martin’s quest for redemption in the comforts of his old life becomes entangled in the machinations of his present life, as he cannot outrun the reality of “making big money, killing important people.” The interesting targets have all dried up, the old romance of political adventurism has evaporated, the hit has been reduced from a statement to a transaction. Martin’s newfound desire to be enveloped in something larger and lasting draws him toward a reconciliation with the people he had previously dismissed as marks, citizens and game players.

Assassin Essay: Related — Review: Franck Ribière’s ‘The Most Assassinated Woman in the World’

Martin’s alienation and boredom drive him to try and cast off his baggage as an historical actor, to recreate a timeline in which he settled into the continuity of normal ambition. He tells his shrink, Dr. Oatman (Alan Arkin), that he doesn’t know what he has in common with anyone — those who have “made themselves a part of something, bought into society.” The hitman is the ultimate expression of atomized individuality, they exemplify a nation of competitors. Martin’s interactions with Grocer are done at gunpoint, violence becomes quotidian. What the aforementioned Besson had begun, Quentin Tarantino took further, and the shadow of Pulp Fiction (1994) hangs heavy over Grosse Pointe Blank — promotional standees of the Pulp Fiction cast are visible during a riotous convenience store shootout that seems like a parody of the stylized slaughter that became a staple as the decade progressed. It marks the slow seepage of violence into the vernacular of everyday life, the Muzakification of death, the erosion of true experience. The thing itself and its representation are conflated; the store clerk listens to “Ace of Spades” on his Walkman and plays the Doom II arcade game while actual bullets fly around him. What had previously been the domain of discreet sectors had burst into the public sphere — everyone wanted to take their shot and exert authority, and the market was more than willing to provide the weapons. The reunion itself is a sort of battleground; Martin calls it “a special torture” as he faces up to everything he has forsworn since he joined the army and was “loaned out to a CIA-sponsored program.” He is a freakish curiosity at this “festival of pain” in which everyone is seeking validation for their decisions. His only defense is sarcasm, the smirking distance of Faith No More’s “We Care a Lot,” which plays as they enter the hall. But Martin is thunderstruck when he looks into the eyes of a classmate’s baby; he catches a glimpse of something that melts his irony, the recognition that perhaps he is “not broken, just mildly sprained,” as Debi describes it.

Assassin Essay: Related — Know the Cast & Characters: ‘Sniper: Assassin’s End’

Just as it seems like Martin has shrugged off the burden of history, it rages back in the form of hitman Felix La PuBelle (Benny Urquidez), who has been hired to eliminate him. Martin kills Felix outside his old locker, and he must explain “it’s not me” when Debi finds him crouched over a bloodstained body. It is the age-old “this is not who we are” justification of the remorseful hegemon, what the empire tells itself whenever it needs to get its hands dirty — its actions do not detract from its fundamental goodness. But in setting out to explain the last decade of his life, Martin lets Debi in on how it really works for those who have chosen to place themselves at the service of the empire. He tells her that “the idea of governments and nations is public relations theory at this point,” that people in his field find an ideological rationale for what they do, his preferred one was “taming unchecked aggression,” but he concedes “that’s all bullshit,” and when it all comes down to it, “you get to like it.” Martin is afflicted with the “moral flexibility” that attends any appendage of the deep state, straining for the ends that sanctify the means, intoxicated by history and looking for the next high. But he understands that it’s time to get clean, escape the fog that has dulled his senses and embrace the clarity of the post-historical subject, free to travel an expanse of serene, featureless highways.

Assassin Essay: Related — Someone Else’s War: A Reckoning with Clint Eastwood’s ‘American Sniper’

Not everyone was content to accept the new historical formulation; two pillars of the 1980s action cycle took up the challenge of upholding the old adversarial posture, reaching different conclusions. In Assassins (1995), Sylvester Stallone plays Richard Rath, another killer for hire who wants out, but the big money contracts keep coming and he puts aside his reservations. However, Rath finds that his contracts are being compromised by a young upstart, Miguel Bain (Antonio Banderas), who seems to revel in the chaos he creates. Rath begins to suspect that his shadowy employer is plotting to have him phased out for a younger model, one more attuned to the tenor of the times. Stallone’s assassin describes himself as a “government employee,” a bloodless functionary dispensing death at the behest of broader motives, while Bain operates according to a less predictable credo. He is emotional and erratic, an avatar for the new supremacy of the self in a post-ideological world. Bain is not concerned with upholding a balance of power, only pursuing his own motivations. Rath’s taciturn professionalism seems increasingly outdated in a milieu where everything is up for grabs, where the old gentlemen’s agreements between the warring parties is washed away and a new mercenary spirit is ascendant. Bain mocks Rath’s desire to “protect the innocent.” “That’s weak,” he says, “You are antiquado.” Faced with this reality, Rath begins to doubt himself, and when the myths that had sustained his life begin to unravel before his eyes, he understands that “the history stops here” and it’s time to surrender.

Assassin Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Sniper: G.R.I.T.’

The Jackal (1997) maintains a convinced Cold War mindset, despite taking place in the chaotic aftermath of the economic “shock therapy” that was imposed on post-Soviet Russia, and gave rise to oligarchs and hoods. One such hood, Terek Murad (David Hayman), hires the Jackal (Bruce Willis) to exact revenge on the FBI for killing his brother, and a former IRA sniper, Declan Mulqueen (Richard Gere), is recruited to help track down the Jackal before he reaches his target. This was the first dawning of a suspicion that the U.S. may have created the conditions for a new nationalism to arise in the vanquished East. The Jackal is a kind of emissary for the values that will animate this backlash against the new liberal order; he is a product of the depredations that prevailed in the pursuit of global supremacy, unwilling to bow like Mulqueen to the new era’s conciliatory disposition. Unlike Martin in Grosse Pointe Blank, the Jackal carries no psychological baggage, insecurity or doubt; there is no compunction, no desire for acceptance, he evinces a detached masculinity that is the stuff of Tony Soprano’s ideal. There is no shortage of retrograde spectacle; the Jackal wears a series of elaborate disguises that harken back to a previous age of espionage drama, to a time when the battle lines were clear; he is a vision of opportunistic manhood, moving from one carefully constructed ruse to the next. The revelation of the target is illuminating, as it speaks to a revanchist streak which turns private antagonisms into political enmity — the First Lady is in the crosshairs, at a time when the position had never been more contentious with Hillary Clinton being a lightning rod for conservative animus. The Jackal makes clear that the old mentality isn’t going down without a fight — the belief that it is incumbent upon a man to “protect your women,” that the hard-bitten individualist of the Reaganite imagination is the only one capable of tilting history to its will.

Assassin Essay: Related — Know the Cast: ‘Le Samouraï’

The old codes had begun to crumble from the shock of historical realignment, but in Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), we see new, singular credos being erected in marginalized sectors of the empire. Ghost Dog (Forest Whitaker) is not an insider — he has no institutional credentials, no military or intelligence background; he is simply the “loyal retainer” of small-time gangster Louie (John Tormey), to whom he owes a debt after the man saved his life. Ghost Dog performs hits for Louie, all the time living according to his approximation of the samurai code, with the book Hagakure as his guide, quoting passages on the correct conduct of the warrior class while living on a rooftop among the homing pigeons who serve as his connection to the world. Ghost Dog is called upon to whack a made man, but when the hit doesn’t go as planned, Louie is called in for a sit down with local mob boss, Ray Vargo (Henry Silva). He explains his unusual arrangement with Ghost Dog to Vargo and incredulous foot soldiers, and it is decided that Whitaker’s character must be eliminated. Jarmusch’s film speaks to a world beyond the prevailing orthodoxy of 20th century exigency, one which is equally freighted with ancient beliefs and liberated by the self-creation of late-stage capitalism; Ghost Dog responds as much to hip-hop bravado as feudal Japanese discipline. The book Rashomon is passed between the characters; a classic fable on the inherent subjectivity of perception which serves to underscore the degree to which multifarious viewpoints overlap and intersect in the new global community, the stasis of intractable blocs eroding. Ghost Dog’s best friend is ice cream man Raymond (Isaach De Bankolé), with whom the assassin doesn’t share a language, but their thoughts coalesce, and they express the same things in English and French.

Assassin Essay: Related — Soundtracks of Cinema: ‘Hit Man’

Louie explains to Vargo that Ghost Dog has taken on his new name like a rapper, but Silva’s character compares it to Native American naming conventions. Ghost Dog unfolds like an urban western, and those who struggle on the fringes of the dominant economic system constitute the Indians of this story, the latest in a long line of designated Indians, those who land outside the ambit of American authority. Vargo’s foot soldiers venture into hostile territory with weapons drawn, their codes clashing with perceptions of strength and honor that do not cleave to the accepted breadth of history. Vargo’s crew strives to keep wild America at bay, stalking the rooftops, asking anyone whose provenance isn’t immediately clear “What the hell are you?” On one rooftop, they encounter Nobody (Gary Farmer), a Cayuga Indian reprising his role from Dead Man (1995), who repeats his refrain: “Stupid fucking white man.” Ghost Dog operates as an almost elemental force, a “revengeful ghost” born for the demands of the streets but endowed with an awareness that life is felt most acutely when it is lived on the precipice of death, reciting a passage from Hagakure which declares: “One should consider himself as dead.” Nature is Ghost Dog’s constant companion; animals serve as portents and guides on his journey, providing insights from beyond what is immediately perceived, the vainglory of historical advantage. Ghost Dog’s life is one of studied renunciation, a devoted retreat from the territorial disputes which keep the local mobsters in a constant state of agitation, emptying their weapons at lengthening shadows. But all Jarmusch’s characters are equally in the dark, grasping for meaning in the depths of an empire that is decaying even at its apparent apotheosis, alive to the urgency of this brief cessation. “Armagideon Time” by Willi Williams blasts from Ghost Dog’s stolen car, echoing the injustice and suffering he witnesses as he crosses the benighted streets of his neighborhood.

Assassin Essay: Related — Constructing a Madman: Lee Harvey Oswald’s Screen Life

Pre-millennial tension only served to heighten the anxieties of a newly unipolar world — Louie complains that “everything seems to be changing all around us” and “nothing makes sense anymore.” For the wise guys, history’s end is proving to be disorienting; their aging, waning ranks try to exert control by invoking discredited traditions, placing their faith in the infallibility of their antecedents and the strength of their weapons. But nothing is permanent, as even Vargo’s country hideout is up for sale, and their sense of mastery is illusory. Ghost Dog confronts two hunters who have bagged a black bear, telling them that “in ancient cultures, bears were considered equal with men” before killing them. Whitaker’s assassin represents the return of the real, thriving in the face of deprivation, harnessing “the spirit of the age” in his elimination of Vargo’s entire crew — his victims can’t help but admire that Ghost Dog is “sending us out the old way, like real fucking gangsters.” He rescues his targets from the simulacrum in which they’ve been languishing — the gangsters watch various cartoon evocations of violence, escalating to the point of Itchy and Scratchy scaling the planet with giant guns. The final standoff between Ghost Dog and Louie is significantly less dramatic; they are the final representatives of “different ancient tribes” that are “almost extinct,” and their customs now appear ridiculous as they play out “the final shootout scene.” Ghost Dog has done all he wanted; he has passed on his copy of Hagakure to neighborhood girl Pearline (Camille Winbush) — his Frankenstein’s monster of an existence has met its natural end. The death that Ghost Dog hands out is intended as “a rainstorm” that clarifies and clears the way for ancient wisdom to perpetuate. We now know this was not how events transpired in reality; the rupture that revived history did not bring us closer to a unified understanding but was designed to precipitate deep-rooted divisions.

D.M. Palmer (@MrDMPalmer) is a writer based in Sheffield, UK. He has contributed to sites like HeyUGuys, The Shiznit, Sabotage Times, Roobla, Column F, The State of the Arts and Film Inquiry. He has a propensity to wax lyrical about Film Noir on the slightest provocation, which makes him a hit at parties. The detritus of his creative outpourings can be found at waxbarricades.wordpress.com.

Assassin Essay: Related — Choose Death: Gregg Araki’s Apocalyptic 90s

You must be logged in to post a comment.