There’s been a trend happening in the last few years: “bad” films such as Waterworld, The Matrix sequels and — gasp — even the Star Wars prequels spoken of in favorable, even laudatory terms. Conversely, there’s been discussion of Oscar-winning popular films such as Green Book or Bohemian Rhapsody that all but trashes those movies, not letting the status which their laurels would seem to earn them dictate opinion. For an alarmingly large number of people, such discussions look bizarre, and these opinions become labeled in some dismissive fashion with words like “contrarian” and phrases like “this movie is for the fans,” the latter a favorite saying of no less than people who actually make films. Such dissenting discussions and opinions should not be regarded as outliers, however, for they are in fact the very core of criticism itself. Criticism’s major contribution to the arts is to provide a diverse number of viewpoints, interpretations and opinions about the critic’s medium of choice — in this case, cinema. Rather than being a service that provides objective, quantifiable rulings, criticism is instead an art all its own that provides a road map to the reader, giving them points of triangulation so that they arrive at making up their own mind.

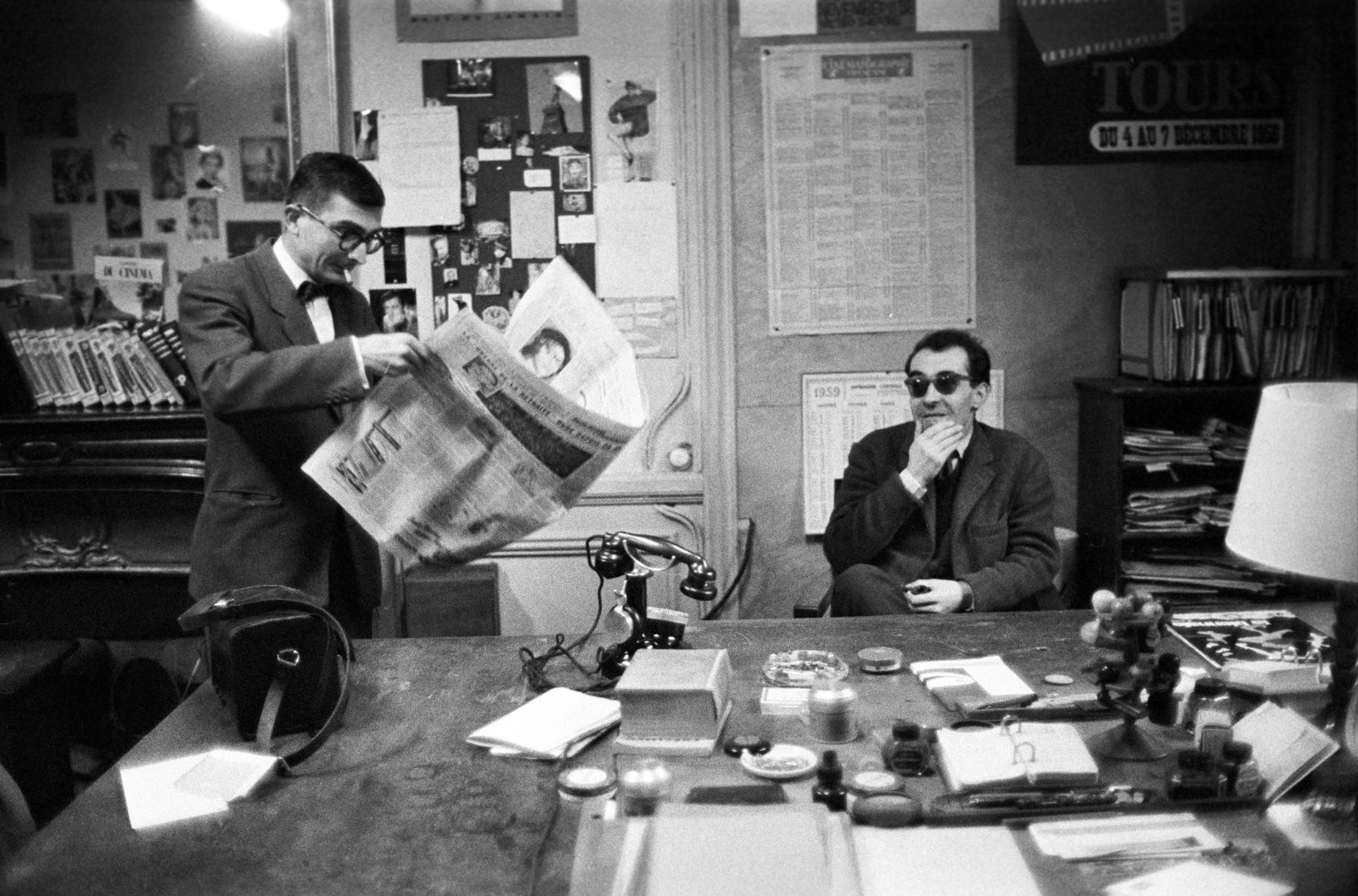

A big part of the trouble facing the role of the film critic today stems from the many past decades when criticism was relatively scarce, allowing a select few to rise to the top and become tastemakers, if not celebrities in their own right. For a long time, film critics were either people working for a local newspaper, or people working in one of the big cities whose reviews were nationally syndicated or published in magazines, like Pauline Kael. A star rating system began appearing in film reviews around the 1930s, and the famous French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma helped push them into widespread usage in the 50s, allowing other grading systems to follow, such as letters and numbers. As television news started to become more specialized and expanded in the 70s, film critics began to get airtime, resulting in TV personalities like Leonard Maltin, Gene Shalit and, of course, Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel. The format and time constraints of such television appearances demanded that these critics provide quick, snappy summations of their opinions and reviews, resulting in things like Siskel & Ebert’s two thumbs up or down rating. Soon, it wasn’t the content of a review that created a consensus of opinion about a film — it was a rating, with star ratings turning up just about everywhere, even in weekly TV guides. In addition to awards shows like the Oscars and Golden Globes, a film’s rating was used to define any discussion of a movie.

Why Criticism: Film as a Business First

While the ability to form one’s own opinion of course existed during this era, it was understandably affected by desire for a majority opinion as well as having just such a thing imposed by popular critics. Bizarrely, this problem only got worse, not better, with the rise of the internet and social media. While critical thought about film became more diverse thanks to more and more writers being given space, there arose a plethora of opinions flooding every corner of message boards, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, and the opinions that went viral started to make film criticism sound like an echo chamber. Obviously, this is an issue that continues to this day, the apotheosis of which is the website Rotten Tomatoes. That site, in theory, is a great one — bring together as many critics and their opinions as possible and have an algorithm boil down their reviews into a single statistic. Yet while the site may have intended that “Fresh” or “Rotten” percentage number to be the beginning of a conversation, most people treat it as the end of one. The film industry hasn’t helped at all in this case, since they quickly realized they could use a “Fresh” rating as a marketing tool, using it not as a consensus but as a seal of quality. Anecdotally, most people who visit Rotten Tomatoes to find out about a film tend to glance at the percentage rating and move on, rather than read any of the full-length reviews that make up the “Tomatometer.”

However, there exists a far more troubling subset of film criticism that makes it into something dictatorial rather than democratic. While people’s desire for convenience turns reviews into quickly aggregated statistics, the trend of YouTube videos touting “X Movie Explained!” strikes at an audience’s abhorrence of nuance and ambiguity. The trend started likely thanks to comic book movies and their post-credits scenes filled with vague references to geek lore, but it has now expanded to include virtually any popular film, no matter how straightforward it may be. These videos reduce film criticism and theory to yet another majority rule, this time about how the art is interpreted rather than just its place in pop culture as “Fresh” or “Rotten.” They act as a sort of Cliff’s Notes for movies, but with the addition of one particular interpretation or viewpoint, and thus become an easy gateway for subscribing to distasteful theories about a film or group of films. The sadly popular channel CinemaSins is the ultimate example of viewing film criticism as merely an exercise, with a literal checklist of what makes a movie good or bad. The people behind these videos would likely defend them as entertainment, and not actual criticism, but their damage has been done nonetheless, devaluing the role of the critic enough to make the art of criticism seem like nothing more than ticking a box and offering a grade.

Why Criticism: Against Nostalgia

All of this is why real criticism is so important to support and engage with. As a college student, I spent hours in my school’s library reading through the stacks of books on film, including one dictionary-like tome that collected nationally syndicated reviews from newspapers by release date, meaning I’d find several competing reviews of 1986’s Aliens one after the other, for instance. I combined that with years of reading new writers online, classic books by Kael, Donald Spoto and Vito Russo, reruns of Siskel & Ebert’s show, and so on. Today, there is a wealth of ways to engage with film criticism, in everything from thoughtful YouTube videos to Twitch streams to podcasts to books to social media to this very site you’re now reading. The goal of such engagement, like criticism itself, isn’t to reach a final verdict but to get as wide an understanding as possible of disparate viewpoints that allows a personal opinion to emerge naturally. A negative review shouldn’t be seen as describing a defective machine, but rather an explanation of why a film failed the writer, which in turn may speak to why it failed the reader, too. A positive review shouldn’t be blown smoke that could be used solely for marketing purposes, but instead an examination of why a film works for the writer (and, again, perhaps the reader, too). Most reviews, despite their star or letter rating, land somewhere between “Fresh” and “Rotten,” making their value exist in their discussion rather than their headline. With any film (good or bad), a look into their resonance, thematic ideas, place in history or a number of other topics can still be of value regardless of culture’s consensus ruling on it or even one’s own. Film criticism is so vital not because it’s a service, but because it’s a tool — a way for each person to arrive at the final word on each film they see from the critic that matters most: themselves.

Bill Bria (@billbria) is a writer, actor, songwriter and comedian. ‘Sam & Bill Are Huge,’ his 2017 comedy music album with partner Sam Haft, reached #1 on an Amazon Best Sellers list, and the duo maintains an active YouTube channel and plays regularly all across the country. Bill‘s acting credits include an episode of HBO’s ‘Boardwalk Empire’ and a featured parts in Netflix’s ‘Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’ and CBS’ ‘Instinct.’ His film writing can also be seen at Crooked Marquee as well as his own website. Bill lives in New York City.

2 replies »