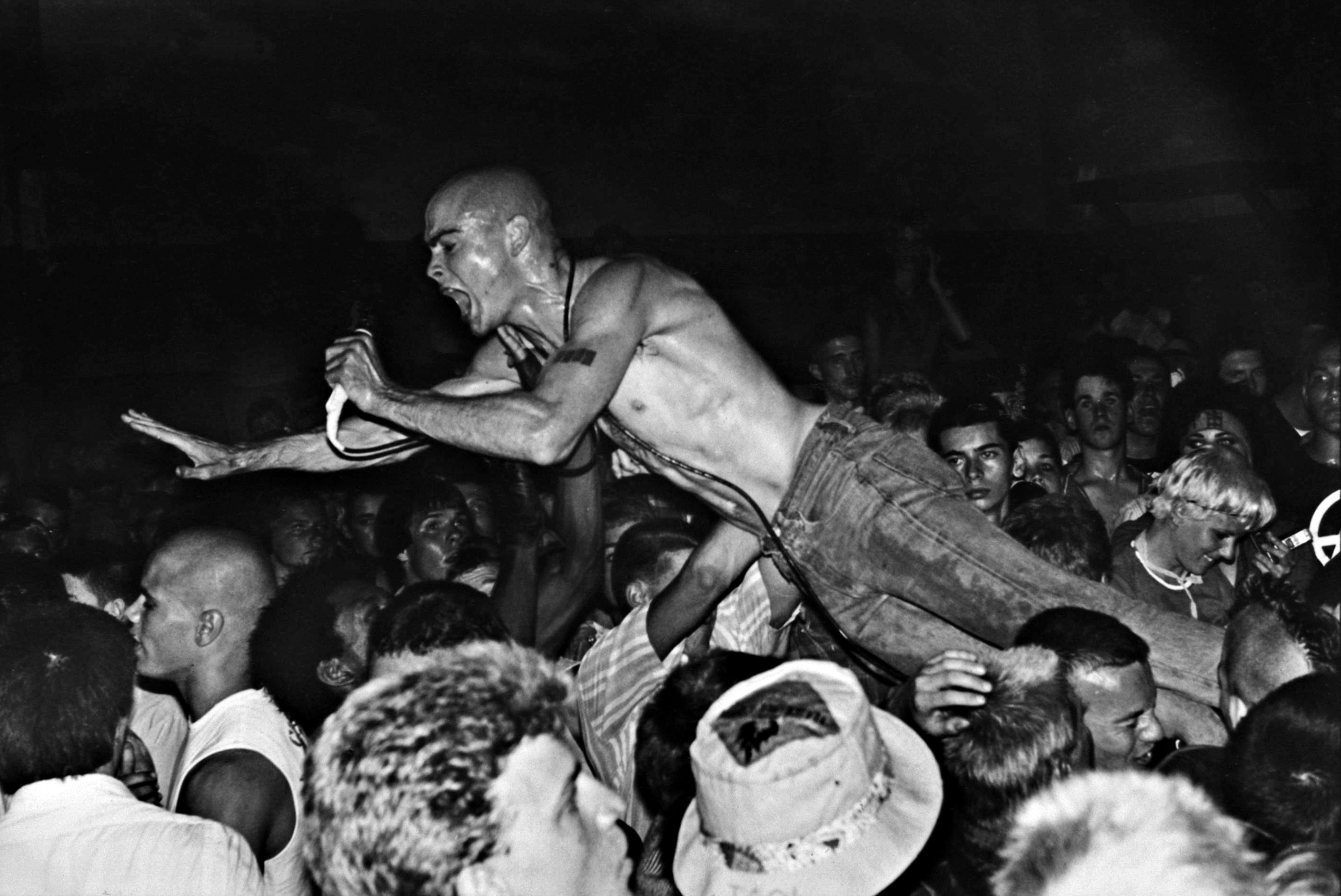

Cinema has been more than willing to follow Azerrad’s lead, adhering to his timeline and profiling his elect. American Hardcore (2006) adapts Steven Blush’s “tribal history” of hardcore punk into an exuberant, if overly affectionate, overview of the movement’s various strands. Blush positions hardcore as a reaction to Ronald Reagan’s America, which foundered upon Reagan’s re-election in ’84, as well as the weight of its own rigidity, but succeeded in seeding the DIY ethos. All of the venerable talking heads are present — Henry Rollins, Ian MacKaye, Mike Watt, Keith Morris, Flea — who largely repeat the observations they’ve made elsewhere in the ever-expanding corpus of punk scholarship. Hardcore unmoored punk from its rhythm and blues lineage and turned it into a pure distillation of predominantly male rage, though it was still capable of throwing up oddities like Flipper. American Hardcore’s most illuminating segments document the scene’s steady slide into sectarianism with the ascendency of the “jock” punk, whose emergence transformed its solidarity into varying forms of chauvinism.

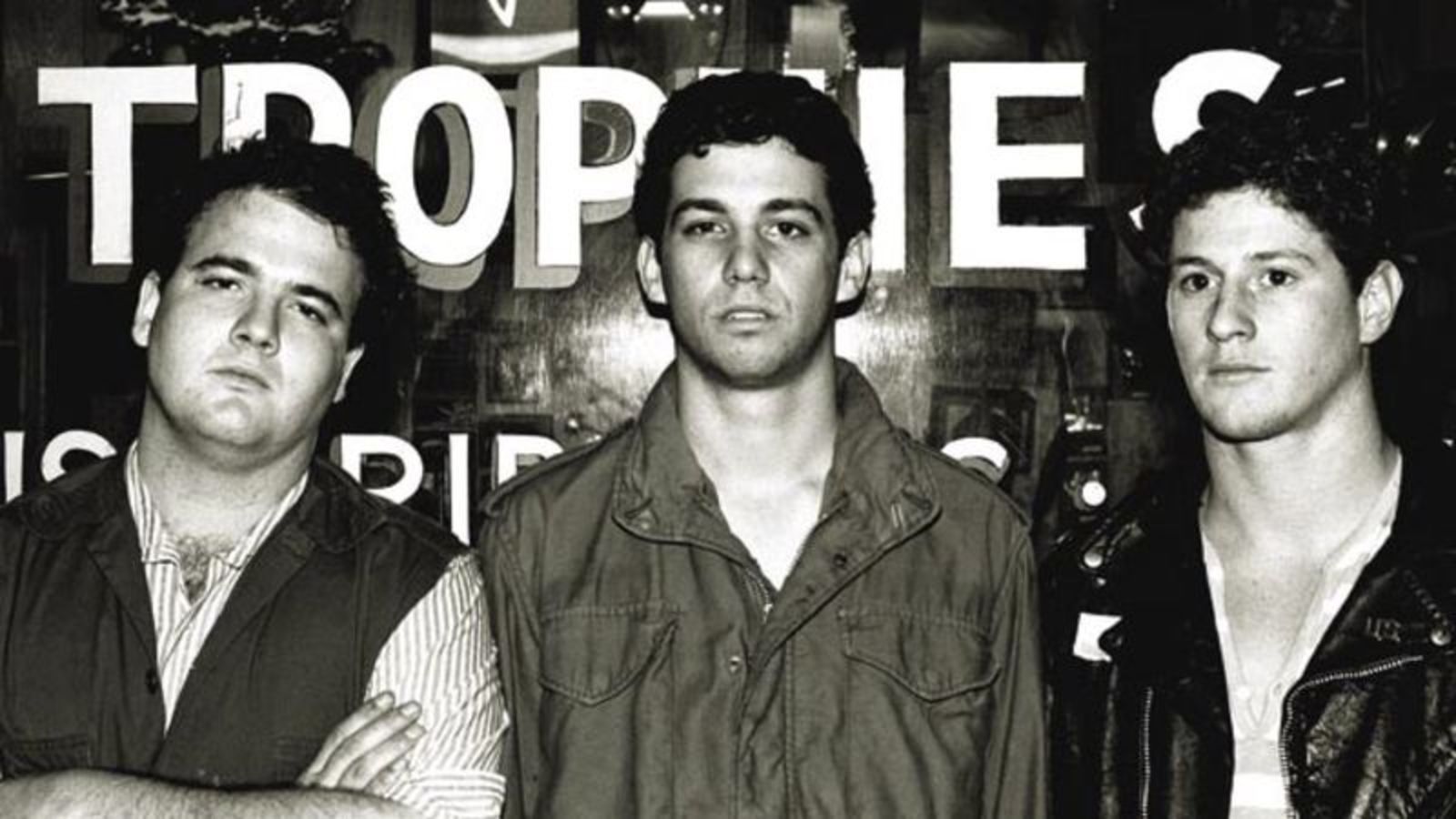

Revulsion at the violence which had overtaken hardcore, and disillusionment with the creative orthodoxy which was creeping in, sent many of its leading lights in search of more fecund territory. It was then that what is now recognized as “indie rock” began to develop, with bands like Hüsker Dü, Mission of Burma, Big Black and the Minutemen expanding the lexicon of guitar music. Tim Irwin’s We Jam Econo: the Story of the Minutemen (2006) is one of the most perfectly realised music documentaries ever made, a seamless convergence of subject and form. Irwin shoots in a consciously low-fi style which is entirely in keeping with the spirit of the Minutemen; viewers are in the passenger seat as the band’s bassist, Mike Watt, drives the van and holds forth without a scintilla of bitterness of cynicism. Just listening to Watt is an inspiration, he is true believer who has retained his sense of wonder at the possibilities of his vocation. Watt’s emotion and sincerity is clear as he recounts what amounts to a tempestuous love affair with the band’s late frontman and guitarist, D. Boon. The film constitutes an attempt by Watt to not only preserve Boon’s legacy, but to retrieve a missing piece of himself in his recollections, to speak once again in their secret language.

K Records emerged in ’82 to take its place alongside SST, Touch and Go and Dischord as one of the premier outlets for underground guitar music. K offered an antidote to the macho complexion so much of punk had taken by expanding the field of representation, championing music which had the feel of outsider art in its repudiation and deconstruction of traditional formulations. Co-founded by Calvin Johnson, K became the vehicle for Johnson’s band, Beat Happening, who were the torch bearers for a style of indie rock which veered towards the jangly and primitive, and was distinguished by Johnson’s seductive yet unsettling baritone. Beat Happening have been derided as proto-hipsters, but songs like “Indian Summer” have the feel of the Velvet Underground at their most elegiac. In the context of hardcore, melody becomes subversive, and Beat Happening upended rock conventions like few others. Heather Rose Dominic’s The Shield Around the K: The Story of K Records (2000) has a suitably scrappy quality; it is the visual equivalent of a fanzine, a passion project which makes up in energy what it lacks in technical finesse. Dominic’s film is as much about the milieu as the music; it outlines what K was able to create in Olympia, Washington; its role in fostering and documenting the talent in this creative community, with little regard for the commercial possibilities of its roster.

Azerrad is one of The Shield Around the K’s primary talking heads, and he draws an interesting parallel between K and fellow Washington label Sub Pop whose slogan is “World Domination” — though a degree of irony is inferred — while K’s slogan is “The International Pop Underground.” It is a conquest model versus a resistance model of commerce; though Azerrad qualifies this somewhat by pointing out that Johnson is “a great networker” and “the cult leader” of the International Pop Underground. Johnson conceives himself as a Warhol figure, creating “an art factory” which facilitates the talents of those around him, empowering people who had never thought they could explore their creativity. The levelling tendency of the K crowd is outlined by the International Pop Underground Convention Johnson organised, the six-day “tribal gathering of ’91” at Olympia’s Capitol Theater. Johnson sought to diminish the distance between performer and audience, an impulse underlined by the fact that Ian MacKaye worked the door after Fugazi’s performance. Though it occasionally gets lost in technical minutiae, The Shield Around the K underlines K’s influence on the likes of Homestead/Matador Records head Gerard Cosloy — who was an early champion of K in his fanzine, Conflict — and Kill Rock Stars founder Slim Moon.

Instrument is the most purely cinematic representation of the indie scene, practising a “show” rather than “tell” policy; it occupies the space between a concert film and a biography, utilising a variety of formats, from shaky Super 8 concert footage to artful 16mm portraits. The variety of live footage really brings home how Fugazi were always able to create a unified consciousness onstage, not only between the members of the band, but with its audience. Throughout Instrument, the band articulates a persistent fear of being defined by others: MacKaye summarizes this bind when he says that “If you don’t say anything, then people place things on you. Then if you try to steer it all, you feel like you’re manipulating it.” The film is partly an attempt to meet the curious halfway, to provide a glimpse into the band’s inner-workings, but no more. It is certainly a novelty to see the band interact and articulate their beliefs — this was before Ian MacKaye became a curmudgeonly fixture of countless indie music docs. Fugazi were not swept along on the post-Nevermind tide; they maintained their own course when the industry came calling, and Instrument is a fascinating document of their ability to remain above the fray when the indie scene was strip-mined by the majors, holding firm to MacKaye’s maxim that “To exist independent of the mainstream is a political feat.”

D.M. Palmer (@MrDMPalmer) is a writer based in Sheffield, UK. He has contributed to sites like HeyUGuys, The Shiznit, Sabotage Times, Roobla, Column F, The State of the Arts and Film Inquiry. He has a propensity to wax lyrical about Film Noir on the slightest provocation, which makes him a hit at parties. The detritus of his creative outpourings can be found at waxbarricades.wordpress.com.

Categories: 2019 Film Essays, 2019 Music Essays, Featured, Film Essays, Music Essays

1 reply »